History of the Musée National d’Art Moderne - Centre de création industrielle

The Musée National d’Art Moderne opened under this name in the Palais de Tokyo in June 19471. In this building, which had been constructed ten years earlier, its director, Jean Cassou, was only able to permanently exhibit a collection that was of inconsistent interest but, above all, one that was incomplete.

The origin of the collections was the "Galerie royale du Luxembourg, intended for living artists", created in 1818 in Catherine de Médicis's former palace, then transferred to its orangery in 1886. Designed to be a transitional institution for works destined to go to the Louvre, this collection, which had been elevated to a national status, and whose works would mainly pass to the current Musée d’Orsay, only made its first hesitant and expensive acquisitions of "modern art" in the early 1920s. The first artists included were Henri Matisse, Albert Marquet, Maurice de Vlaminck et Suzanne Valadon, followed in the 1930s by Georges Braque, Robert Delaunay, André Derain, Fernand Léger and even Yves Tanguy, along with many other artists whose names are today forgotten.

Due to the overly dense hanging of works in this small building, in 1922 it was decided to split the Luxembourg collections up by creating an annexe in the former Jeu de Paume in the Tuileries Gardens, devoted to foreign artists. Placed under the direction of André Dezarrois, the Musée national des Écoles Étrangères Contemporaines was granted administrative autonomy in 1930, and its building soon subjected to far-reaching renovation, which placed it at the forefront of museographic practice.

In a difficult situation characterised by a certain administrative recalcitrance, Dezarrois succeeded in acquiring the first paintings for the collections by Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, František Kupka (the museum’s first abstract work), Vassily Kandinsky, not to mention Salvador Dalí and Frida Kahlo.

Bas-reliefs d'Alfred Janniot. Architectes Jean-Claude Dondel + André Aubert + Paul Siard + Marcel Dastuque. Photographie de Pierre Jahan

© Adagp, Paris 2025 © Pierre Jahan/Musée d'Art Moderne/Roger-Viollet

However, the distinction between French and foreign artists was subjected to increasing criticism. In the lead-up to the "Exposition internationale des arts et techniques dans la vie moderne" in 1937, Luxembourg's curator, Louis Hautecœur, managed to convince the state of the need to construct a specific building to house both collections.

This would become the Palais de Tokyo on the butte Chaillot, where the new museum shared space alongside the municipal modern art collections (where the latter are still located), and its construction of which was commissioned from four architects little inclined to associate themselves with the modernist movement. The outbreak of World War II prevented the opening of the institution, as Jean Cassou, its new director, was soon dismissed by the Vichy regime, while the Jeu de Paume was requisitioned by the Germans to hold spoliated works of art.

Following the Liberation of Paris, Cassou, buoyed with the glory of his involvement in the Resistance, was reinstated in his post and, with the support of the directorate of the Musées Nationaux and exceptional funding, was in a position to fill the considerable gaps in the collection.

The expensive acquisition of Picabia’s Udnie [1913], the first sculptures by Constantin Brancusi and Jean Arp, paintings by Georges Braque, Juan Gris and Michel Larionov and the curtain Picasso painted in 1917 for the ballet Parade date from this period.

Owing to his excellent relations with artists, Cassou was able to acquire important works at negociated prices from Matisse, who gave the state his Blouse roumaine [Romanian Blouse] in 1953 [1910]. Cassou also benefited from extreme generosity by Picasso, who donated no fewer than ten recent paintings in 1947, including L’Aubade [1942], as well as from Chagall and his daughter Ida, Joan Miró (and his dealer Pierre Loeb) and Alexander Calder. As for Brancusi, he bequeathed the contents of his studio in 1957.

Major donations were also made by the gallery owner Paul Rosenberg and Baroness Gourgaud, the latter with exceptional paintings by Fernand Léger, Matisse and Picasso. And between 1952 and 1963, more donations from André Lefèvre and his wife, Raoul La Roche and Henri Laugier finally gave Cubism a respectable presence in the collection. During the 1960s, monographic collections, sometimes substantial in both quantity and quality, arrived in the Palais de Tokyo as a result of the generosity of the heirs of leading artists: Jean Arp, Antoine Pevsner, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Raoul Dufy, Zoltán Kemeny, František Kupka, Henri Laurens, Jean Pougny, Georges Rouault, and later Victor Brauner. It is these collections that, even today, endow the museum with a considerable part of its identity.

Yet in spite of these outstanding acquisitions, for many the Cassou years (which ended in 1965) were somewhat disappointing. The weak links in the collections are often pointed out: foreign art, American in particular, geometric abstraction and Surrealism. Contemporary art was also poorly represented, as acquisitions were dependent on another administration, the Bureau des Travaux d’Art, though its choices could be guided by the museum.

The director must however be credited with an active policy of temporary exhibitions, of which the pinnacle was "Les Sources du XXe siècle. Les arts en Europe de 1884 à 1914" [The Sources of the 20th Century. The Arts in Europe from 1884 to 1914], the model for the multidisciplinary exhibitions of general assessment that were to be the hallmark of the Centre Pompidou in its early years.

Poorly loved by its users, the Palais de Tokyo soon showed its technical limitations and the need arose for a new building, for which, at the request in 1964 of André Malraux, the Minister of Culture, Le Corbusier reactivated his plans for a "museum with unlimited growth", which he had designed in the 1930s. The architect’s unexpected death the following year brought the project to an end, but it was soon replaced by one for an ambitious centre for art and culture to house the museum, proposed in 1969 by the new President of the Republic, Georges Pompidou.

Appointed director of the visual arts in 1974 for the prefiguration of the Centre Beaubourg, Pontus Hultén, who came from the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, was eventually given an independent budget and his own acquisition committee. He was thus in a position to make important purchases to fill the most pressing gaps in the historical collections (the first Piet Mondrian entered in 1975), while stepping up the acquisitions that the Centre National d’Art Contemporain, now under his authority, had been making since 1967. Regarding American art in particular, he could count on the generosity of Dominique de Menil, the founder of the "American Friends for Beaubourg", and his sister, Sylvie Boissonnas, through the Scaler Foundation2.

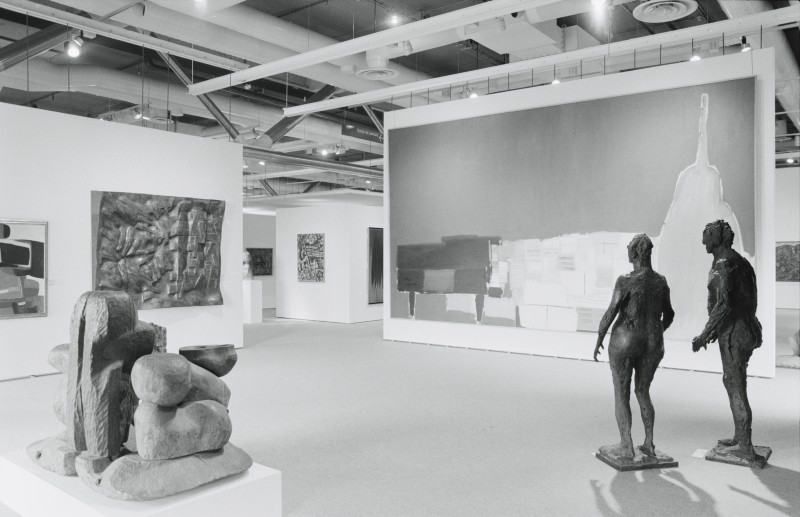

When the Centre designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers opened in 1977, visitors to the museum, of which Hultén had in the meantime been appointed director, discovered a radically altered collection in which drawing, photography, experimental film and video art all now had a place.

In 1981, the substantial bequest made by Kandinsky’s widow, Nina Kandinsky, who had already made considerable donations to the museum in 1966, made the Musée National d'Art Moderne (MNAM) the reference museum for this pioneer of abstraction. Under the direction of Dominique Bozo (1981-86) and with the aid of increased resources, essential acquisitions continued, such as Miró’s large Bleus [1961], for which the museum needed almost ten years to bring together, while the legal procedure of dation3 began to result in the collection receiving important works by "classic artists of the 20th century" (Calder, Chagall, Jean Dubuffet, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, etc.) or from their dealers. One exceptional donation, made by Louise and Michel Leiris in 1982, boosted works by artists that the gallerist Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler had promoted. Daniel Cordier, who had also been a gallery owner before becoming a simple "collector", contributed his unique perspective on the art of the second half of the 20th century to the institution through his regular donations.

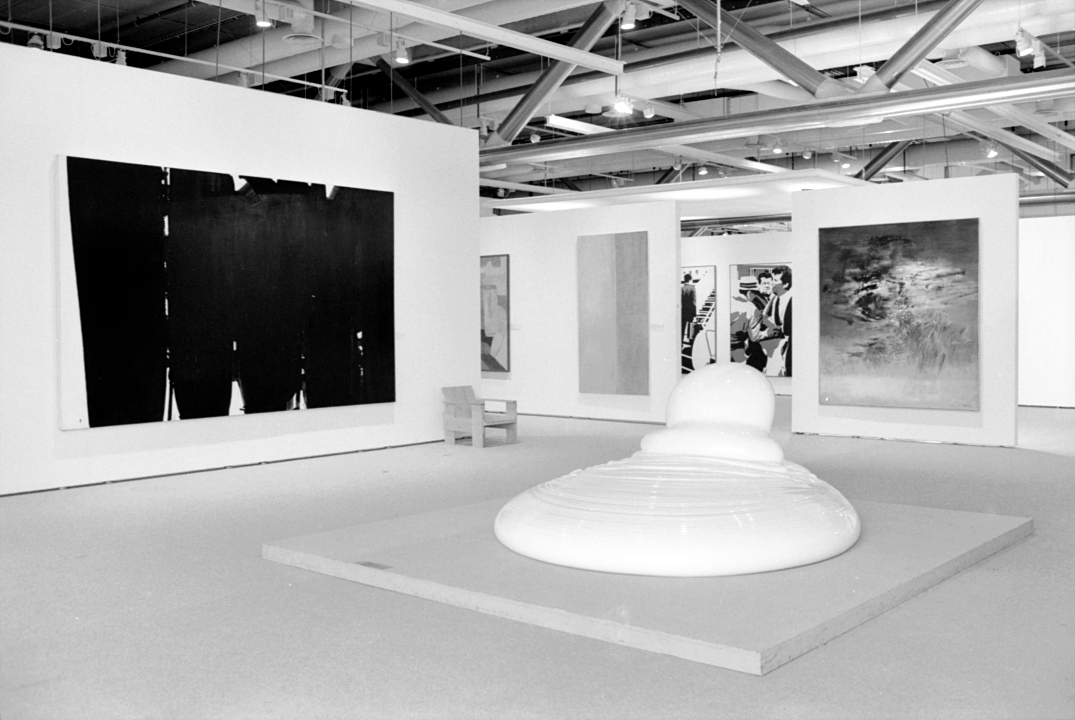

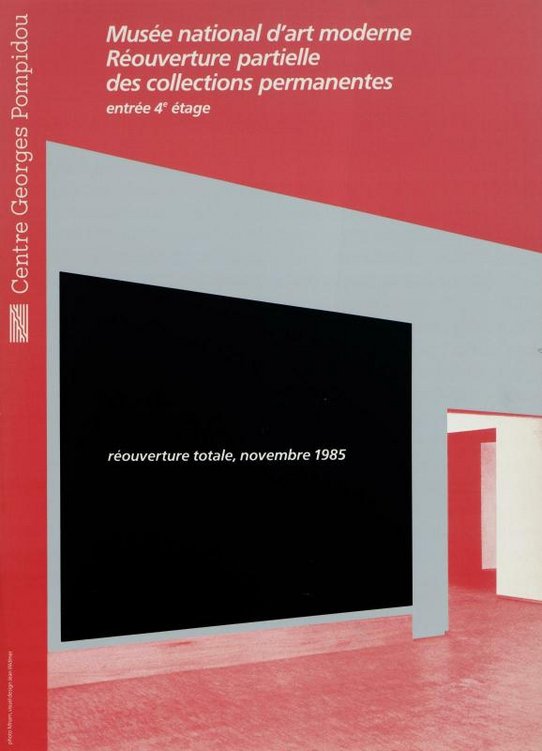

In 1985, only eight years after the Centre Pompidou was inaugurated, a reorganisation and scenography for the historical collections was entrusted to the Italian architect Gae Aulenti (Level 5), a development that was soon repeated for the contemporary collections by Jean-François Bodin (Level 4). In spaces that were by this time densely constructed, but which challenged the modularity intended by the Centre Pompidou's designers, the collection could be further developed, all the more so in 1992, when the museum and the Centre de Création Industrielle (CCI) merged, since the collections were extended to include architecture and design, whose remarkable holdings are developing rapidly.

© Centre Pompidou, 1985 ; Conception graphique : Visuel Design Jean Widmer © ADAGP, Paris, 1985

© Centre Pompidou, 1984 ; Œuvre reproduite : Alain Fleischer, Photo(s) ; Conception graphique : Visuel Design Jean Widmer © ADAGP, Paris 1984

Later directors of the museum have all wished to cultivate this multidisciplinarity by making major heritage acquisitions, while at the same time providing an account of contemporary creation, for which a "Prospective" department has been responsible since 2000.

With regard to acquisitions, in addition to numerous purchases, dations continue to be of the essence, as is evinced by the entry into the collection of the Man Ray set of works in 1994, the wall of André Breton’s studio en 2002 [1922-1966], and Paul Destribats's "petits papiers", which entered the museum’s documentation centre, the Kandinsky Library, in 2020. However, large donations continue to be made, such as the one by Florence and Daniel Guerlain in 2012 dedicated to contemporary drawing, or the very recent one by Bruno Decharme, whose Art Brut collection alone creates a new field of research and acquisition for the museum.

And it was on account of the patronage of Yves Rocher that the photographic collection that formerly belonged to Christian Bouqueret was purchased in 2011. Above all, the lowering of acquisition budgets was fortunately compensated by the generosity of the Amis du Centre Pompidou, whose groups dedicated in particular to contemporary art, design and photography, but also to important geographical areas, bring together collectors and museum curators through their choices.

In the early part of the 21st century, the MNAM-CCI can thus boast a renewed ambition, reflecting not just a globalised collection, but one that also includes more works by women artists, founded on an outstanding representation of the historical avant-gardes.

Notes:

1. The museum had enjoyed a short-lived opening in 1942, during the Occupation.

2. The Clarence Westbury Foundation would later take over from this admirable family-based patronage.

3. A dation allows a French tax-payer to settle taxes with heritage works of major importance.

Christian Briend, "History of the Musée national d'art moderne-CCI", Masterpieces of the Centre Pompidou, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2023