AI, NFT: Vera Molnár, a step ahead

Over the century that she lived through, and right up until her last breath, Vera Molnár kept herself in a state of genuine "creative joy" . To see this for oneself in her final years, all one had to do was to visit her in her flat at her retirement home. Far from a place where people await death, it was a beautiful artist's studio, a new stage in her career: a jar of gherkins on the bedside table, numerous sketches and studies pinned to the walls, an abundant library, geometric shapes everywhere, and her famous Journaux Intimes constantly evolving on her work table. Surprisingly, however, while she is often presented as the queen of code, or at least as a tutelary figure of computer-generated art, no computing machine was to be found.

Is that so surprising? Although she has indeed been coding for several years, Vera Molnár has above all developed an in-depth understanding of the possibilities offered by emerging technologies, confronting them with her extensive knowledge of art history. Her practice has thus become part of a dense temporal and intellectual rhizome: her works include numerous tributes to Albrecht Dürer, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee or Jean-Baptiste Chardin, placing her innovative work at the intersection of several fertile branches of art history.

Vera Molnár has above all developed an in-depth understanding of the possibilities offered by emerging technologies, confronting them with her extensive knowledge of art history.

Encouraged upon her arrival in Paris in 1944 by Sonia Delaunay, Molnár also established strong and fruitful relationships with the artists of her time, such as François Morellet, Victor Vasarely, Aurelie Nemours and Max Bill - to name but a few. She took part in the work of the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel, and founded the Groupe Art et Informatique in 1967. Having the opportunity to travel the world, in the 60s and 70s she visited MIT and Bell Laboratories and explored the vast range of technological and creative possibilities offered by the first computers.

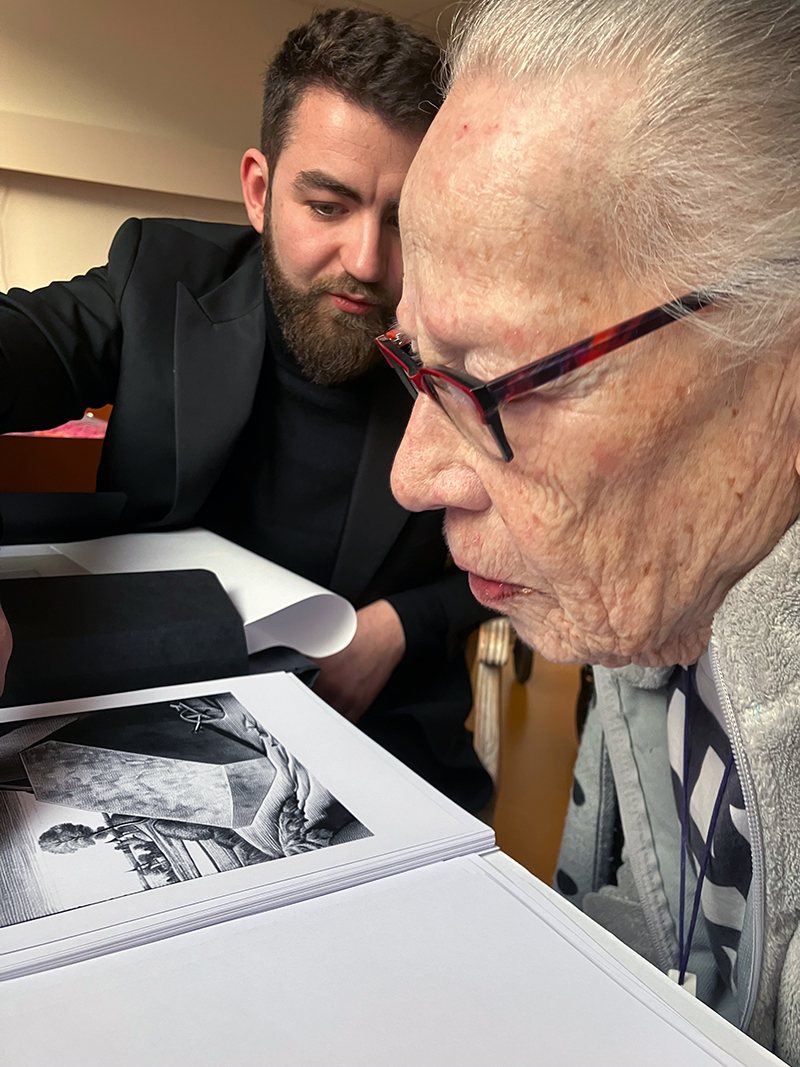

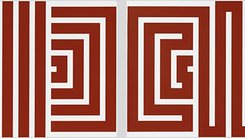

As an engineer, when she lacks the skill to operate these complex machines or the first plotters, she acquires it herself, or surrounds herself with assistants and experts who help her to project the multiple forms of her Journaux Intimes into reality. As she approaches her hundredth birthday, Vera Molnár has lost none of her curiosity or enthusiasm for building bridges between different practices. Under the benevolent eye of her biographer Vincent Baby and a number of other 'Molnarians', she has embarked on a number of exciting adventures and artistic collaborations, exploring new visual techniques with Joannie Lemercier, new digital media such as NFTs (including the series Themes and Variations), reactivating plotters with Julien Gachadoat, and working with my studio, aurèce vettier on AD.VM.AV.IA, a series of 16 works generated in collaboration with an artificial intelligence.

Artificial intelligence. A technology now the subject of all sorts of debates, a new - and more implicit - way of interacting with the machine, which Vera Molnár has been familiar with since the 1980s at least : her works have, in fact, illustrated posters for university conferences on this very subject.

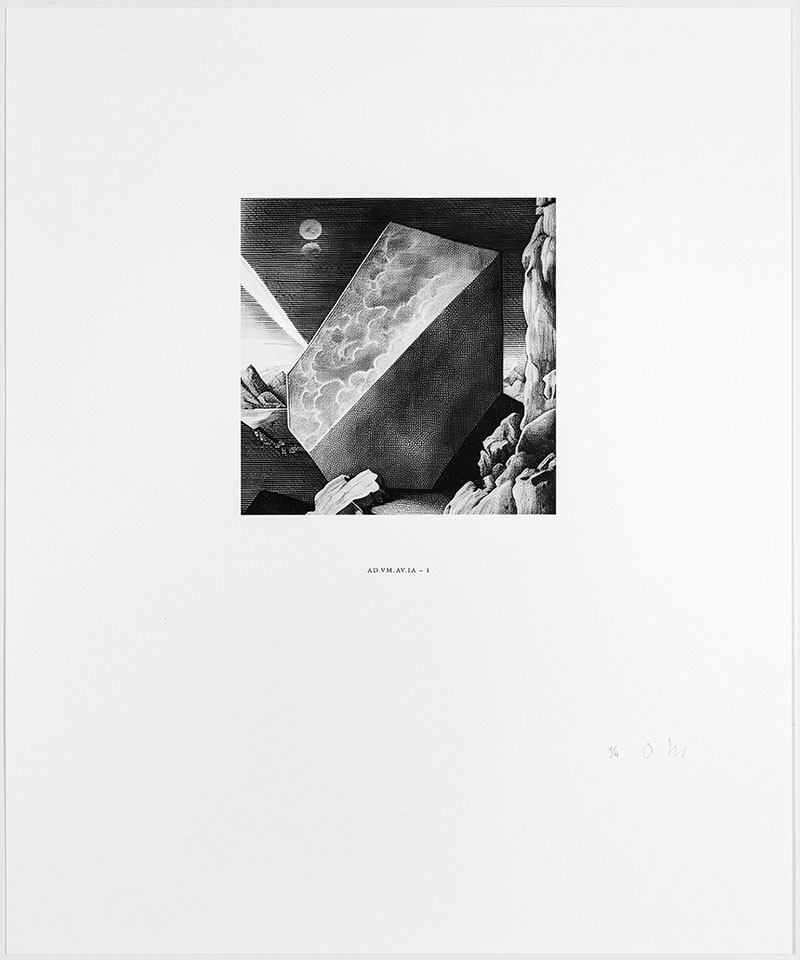

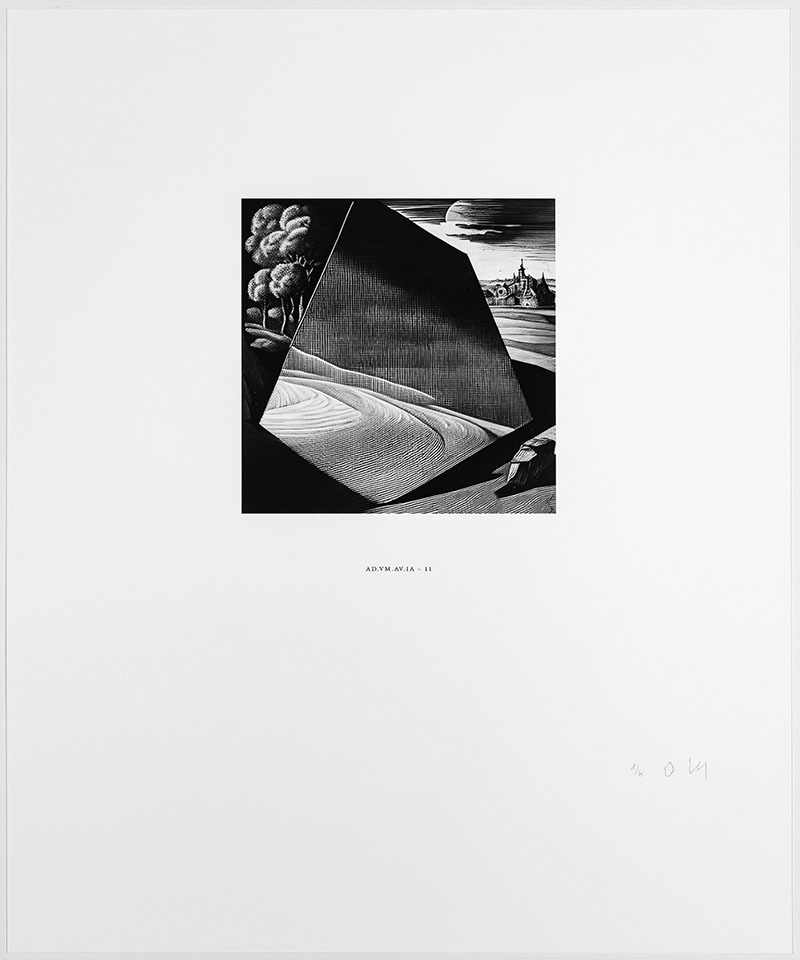

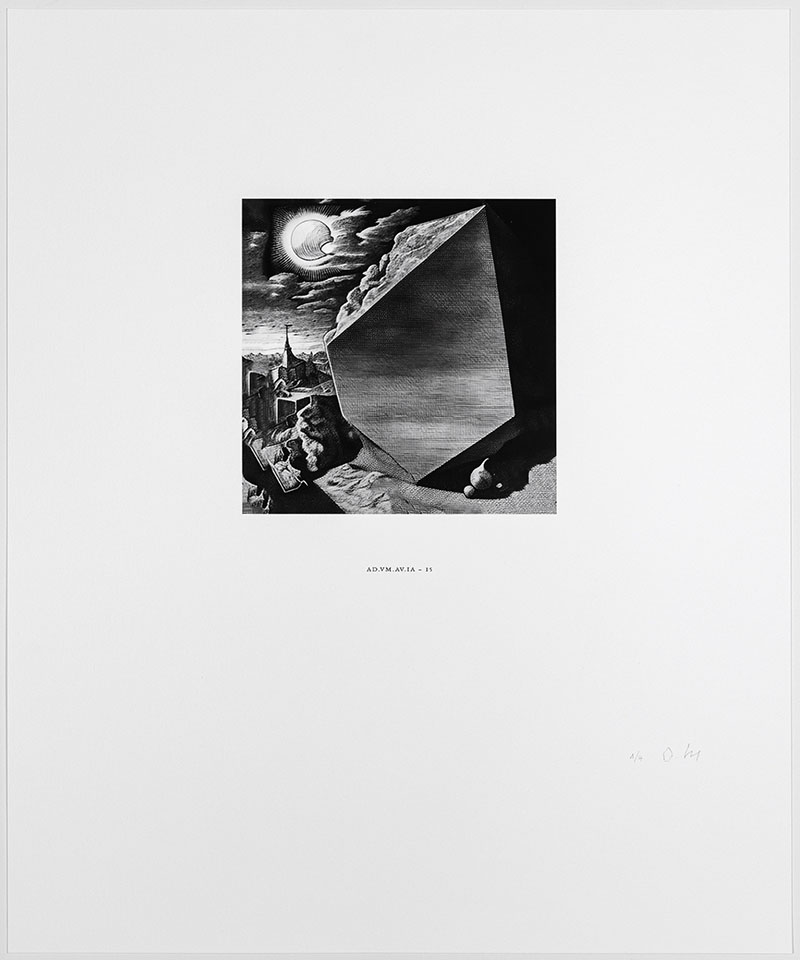

The use of artificial intelligence in artistic creation is an eminently hybrid process, particularly well suited to the approach of Molnár and her Machine Imaginaire (1959). It is, in a way, the fruit of multiple back-and-forths between the real world and the world of the imagination and data. Our work began with a poetic exchange with Vera Molnár about Albrecht Dürer's engraving Melancholia (1514), and in particular the very special polyhedron it contains. "What if we were to stand behind this polyhedron in the engraving? What would be the geometric shape of its hidden face? And what landscapes would we see on the other side? Of course, a mathematician already has the answer: this form, although complex, is well known. This is obviously not the point. On the other hand, because of its ability to absorb data, digest it and create a sort of quintessence of a data set, or even a hallucination, artificial intelligence appears to be a particularly relevant tool for adventure.

Artificial intelligence. A technology now the subject of all sorts of debates, a new - and more implicit - way of interacting with the machine, which Vera Molnár has been familiar with since the 1980s at least.

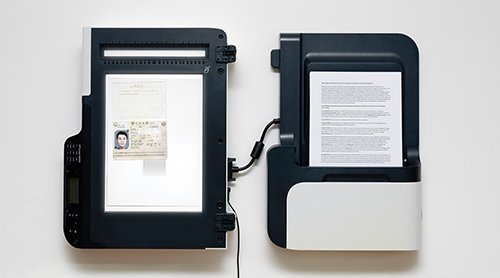

The first step was to feed the machine, by carefully selecting, with Vera Molnár, sketches and engravings by Albrecht Dürer that had fallen into the public domain, and by digitising certain engravings from the collection of aurèce vettier - in particular works by the Jesuit monk Olfert Dapper. Then, back at my studio, I had to fine-tune an artificial intelligence model known as a 'diffusion model', which would allow me to go from text to image, using the huge computing capacity offered by the latest generation of graphics cards. Once the model was ready, using descriptions of the polyhedron and the instruction to stand at the back of it, it became possible to use this tailor-made artificial intelligence to generate 64 initial proposals for "simili-gravures". These 64 proposals were then printed, and 16 of them were jointly selected on the basis of purely subjective aesthetic criteria, in the purest Molnarian tradition, and co-signed. Enthused by the project and its results, in the middle of a work session she stops short to share this tale: "A Chinese emperor orders the most talented painter in his kingdom to depict his favourite rooster, who has just died. He gives him three months. When the deadline passes, the emperor visits the painter, but the portrait is not ready. Just as he is about to severely punish him, the painter takes out a sheet of paper and draws, with exceptional precision, the profile of the much-loved cockerel. The emperor's anger explodes, because the painter would have had plenty of time to draw the portrait, but he wasn't ready. He raises his weapon at the painter, but the latter opens a huge cupboard filled with countless sketches and studies of the rooster in question. The emperor immediately realises how much practice it took to make this portrait, and invites him to his palace to complete the painting."

Over the course of the century she lived through, the young Hungarian professor of aesthetics and art history became a world pioneer in computer-generated art, giving it its first letters of nobility.

Although she did not code during this collaboration, in just a few seconds Vera Molnár demonstrates her perfect understanding of the issues involved in training artificial intelligence: to obtain convincing, even surprising results, you need a large volume of carefully chosen data of excellent quality. Over the course of the century she has lived through, the young Hungarian professor of aesthetics and art history has become a world pioneer in computer-generated art, giving it its first letters of nobility. The branch of art history she helped to develop continues to branch out, through the work of numerous artists paying tribute to her, and whom she often encouraged.

As we prepare to leave the room, she offers me a final gift, flavoured with the kind of humour that is so interesting and so characteristic of Eastern European countries. Is she opening the door to the source of this "1% disorder", this "vulnerability of the right angle" , to a form of emotion at the heart of geometric abstraction, to a clue about her personal relationship to her own work and to death? In any case, her eyes are mischievous, and as she smirks says : "You know, I'd planned to die in May, but I think I'll postpone it a little...". ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Exhibition AD.VM.AV.IA. De l’autre côté du polyèdre, July 2023, Paris.

Photo © Marc Domage