Focus on… "Windows" by Ellsworth Kelly

Born in Newburgh, New York, in 1923, Ellsworth Kelly began studying art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in the early 1940s, before being drafted into the US Army. Assigned to a special unit later known as the “Ghost Army”, he worked in camouflage, landing in Normandy in June 1944 and taking part in the liberation of France. It was then that he first encountered Paris.

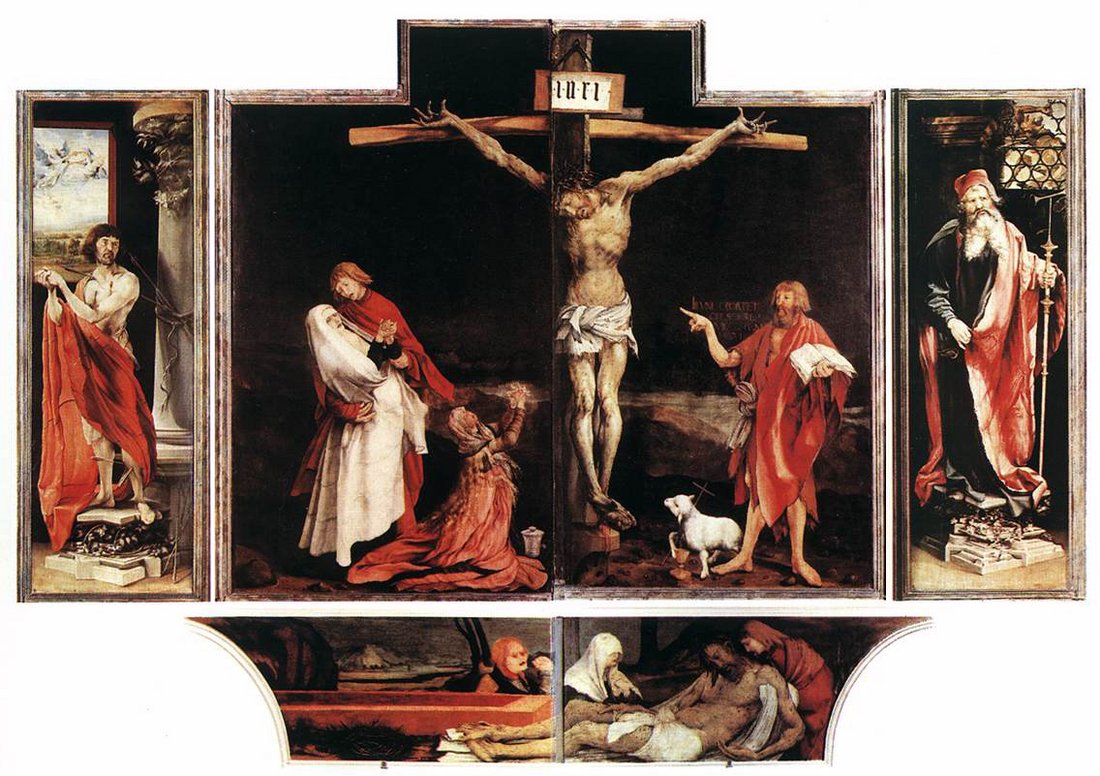

After returning to the United States in 1945, Kelly enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and spent time in major museums along the East Coast. His painting was still figurative. In October 1948, a grant for demobilised soldiers brought him back to France, where he settled in Paris until June 1954. He travelled across the country – seeing Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar, visiting Romanesque churches in Poitou-Charentes – and became a familiar figure in Parisian museums, starting with the Louvre.

Kelly’s work quickly began to shed its figurative roots. In the summer of 1949, during a stay on Belle-Île, he painted Window I: a small black-and-white canvas where the idea of a window is reduced to its bare bones. What remains is a simple cross – part architecture, part observation – shaped as much by telegraph poles in the landscape as by the built world itself.

Back in Paris, Kelly walked the city obsessively, drawn to its architecture and its overlooked details. That autumn, he returned to the window again and again. Window II introduces a subtle, almost human quality. Window III pushes further, becoming a surprising white monochrome, its lines traced not with a brush but with string sewn directly onto the canvas, based on a quick sketch made on the back of an envelope. He also created Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris, a painted construction in wood and canvas that mirrors the proportions of an actual window from the museum itself, then housed in what is now the Palais de Tokyo.

Standing nearly four feet tall, this object-painting marks a turning point for Kelly. It signals the emergence of what he would later call the already made – a concept distinct from Duchamp’s readymade, in that it always involves duplication and transformation. Materials, scale and colour are altered, sometimes subtly, sometimes radically, but the work is never simply displaced. This approach would go on to shape a large part of Kelly’s later practice.

In his Notes of 1969, Kelly reflects on this idea: “After constructing Window with two canvases and a wood frame, I realised that from then on painting as I had known it was finished for me. The new works were to be objects, unsigned, anonymous. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made; it had to be exactly what it was, with nothing superfluous. It was a new freedom: I no longer needed to compose. The subject was there, already made, and everything was material. Everything belonged to me: a factory skylight with its broken and patched panes, the lines of a road map, the corner of a Braque painting, scraps of paper in the street. Everything was the same; everything was usable.”

With Kelly, the window is no longer about transparency. Long associated with painting itself – since Alberti’s De pictura in the early 15th century – it becomes something else entirely: opaque, solid, object-like. Kelly asks us not so much to interpret as to look. The shift is decisive, placing his work at the heart of a new way of thinking about abstraction and the viewer’s role.

In early 1950, he painted Window V, an oil on wood inspired by shadows seen through a hotel window. It was followed by Window VI, the largest of the series, made from two panels of canvas and wood and directly based on a Parisian window – the Swiss Pavilion at the Cité universitaire, designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

As a landmark exhibition at the Jeu de Paume in 1992–93 later showed, Kelly’s years in France were a time of constant invention, one he would return to again and again throughout his career. ◼

Related articles

Ellsworth Kelly, Window VI, 1950 (detail)

Two joined panels, oil on canvas and wood, 66.4 × 159.7 cm

Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, Spencertown