Marlene Dumas: Painting in the Flesh

She may have a French first name, but she doesn’t speak la langue de Molière (“the language of Molière”). Born in South Africa, she has lived in the Netherlands since 1976 and represented the country at the 1995 Venice Biennale, alongside Marijke van Warmerdam and Maria Roosen. Still relatively unknown to the wider public, she nonetheless became the most highly valued living female artist at auction on 14 May 2025, when Miss January (1997) sold for $13.6 million, fees included (around €12.1 million), at Christie’s in New York.

A major figure on the international art scene, she was recently invited by the Louvre to create a permanent work for the Paris institution. With this commission, Marlene Dumas joins the ranks of renowned artists who have left their mark on the museum, from Georges Braque to Cy Twombly, Anselm Kiefer, François Morellet and Joseph Kosuth.

There is no beauty, if it doesn’t show some of the terribleness of life.

Marlene Dumas

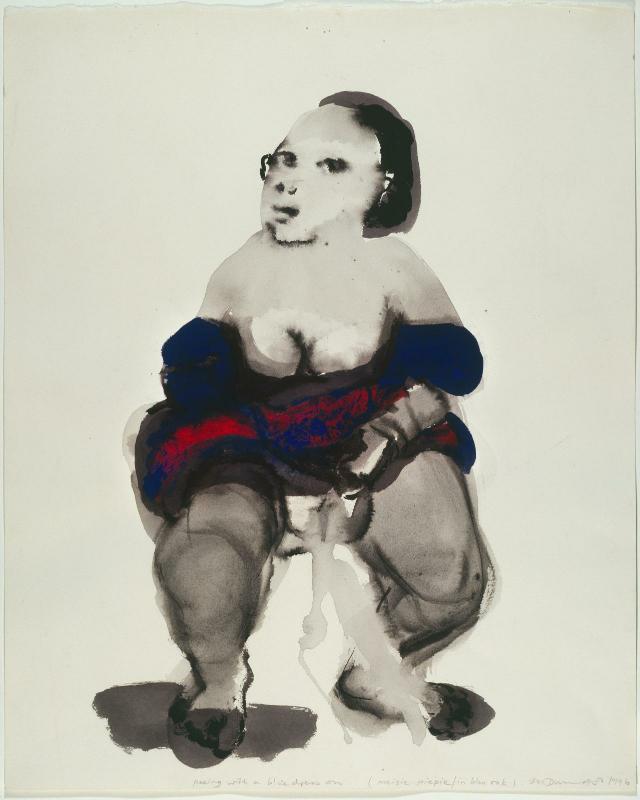

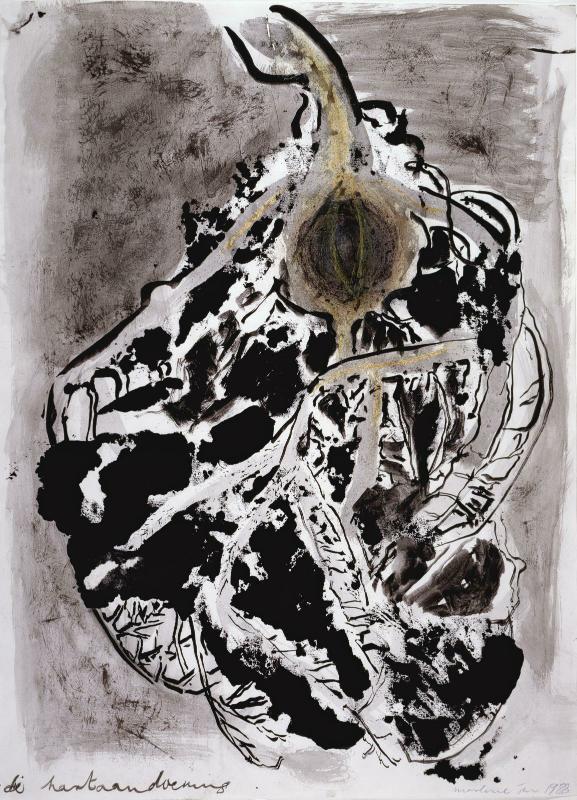

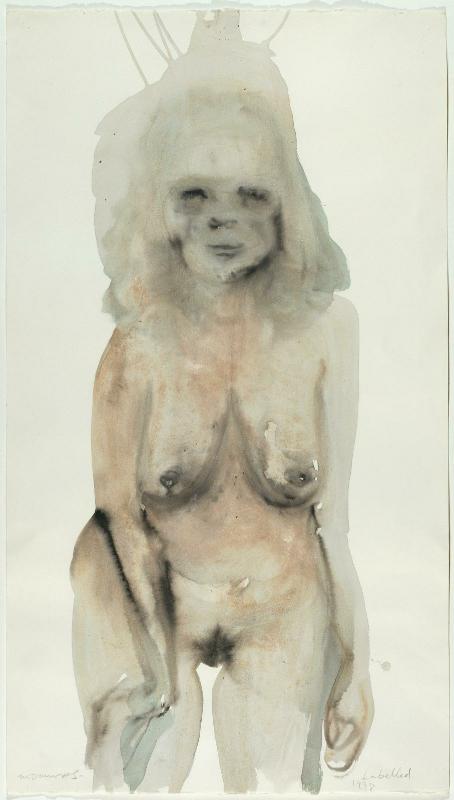

Unveiled in December at the Porte des Lions, near the newly renovated Galerie des Cinq Continents and the paintings department, “Liaisons” comprises nine tightly framed canvases that zoom in on ghostlike faces. Their haunting presence bears the hallmarks of the South African painter’s style: blurred contours, a sombre palette, and diluted washes of turpentine-heavy paint. Echoes of these can be found in six portraits from Mixed Blood and in the nude figure of Labelled — several of the masterworks from the Centre Pompidou’s cabinet d’art graphique, brought together at the Grand Palais in “Dessins sans limite”.

More often than not, the artist strips her figures of any explicit context, placing them in a neutral space. References to reality and archetypes coexist, giving rise to works that cast a meditative gaze on humanity and read like oxymorons: terrible beauty, captivating violence, gentle cruelty, guilty innocence.

More often than not, the artist strips her figures of any explicit context, placing them in a neutral space. References to reality and archetypes coexist, giving rise to works that cast a meditative gaze on humanity and read like oxymorons: terrible beauty, captivating violence, gentle cruelty, guilty innocence. “The first book in my life, teaching me that love and fear go hand in hand,” she once wrote about the Bible — a complex interplay of opposites that has shaped her vision from the very start.

Marlene Dumas grew up in the countryside, twenty-five kilometres from Cape Town, where she was born in 1953 — in Kuils River, on her parents’ wine estate at the beginning of the South African wine route. She loved observing nature, climbing trees, and drawing: her relatives, pin-up girls, beauty queens (so ubiquitous at the time) — but never nature or landscapes. As if she couldn’t quite measure up. What she liked best was drawing as quickly as possible, in a single, simple stroke.

She began studying art at the University of Cape Town in 1972, where she was mainly drawn to modern art and discovered art history through books alone. At the time, as she once wrote: “I thought art was American because of Artforum. I thought that Mondrian was American too, and that Belgium was a part of Holland.” In 1976, she fled apartheid to study at Ateliers 63 in Haarlem, a space founded by artists in search of a radical break from academic traditions. Over the years, it has welcomed students such as Urs Fischer, Aernout Mik, Tatiana Trouvé and Krijn de Kooning, to name just a few.

Dumas first attracted attention in 1978 at the exhibition “Atelier 15: 10 Young Artists” at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. But at twenty-five, she still didn’t quite see herself as an artist. She hadn’t yet embraced the label — as she put it, with irony: “I paint because I’m an artificial blonde woman. (Brunettes have no excuse).” In 1980, she enrolled in psychology, imagining herself as an art therapist, a plan she abandoned after a year of study at the University of Amsterdam. In 1982, Rudi Fuchs invited her to take part in “Documenta 7” in Kassel, where she was among the youngest artists in the show, alongside her fellow student René Daniëls.

My brain is a pile of compost.

Marlene Dumas

She turned her back on American art, which she found too commercial, and found sustenance in the tormented painting of Bacon and Munch, the power of Velázquez, the colour-charged energy of Delacroix, the eroticism of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, and the audacity of Picasso. The Centraal Museum in Utrecht gave her a first solo show of works on paper in 1984 (“Our Country is Lower than the Sea”), followed in 1985 by a painting exhibition at Galerie Paul Andriënne in Amsterdam (“The Eyes of the Creatures of the Night”). Other exhibitions would leave a mark: “The Image is Burden” in 2014 at the Stedelijk Museum (later presented at Tate Modern in London and at Fondation Beyeler in Basel), “Le Spleen de Paris” at the Musée d’Orsay in 2021, and “open-end” at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice in 2022.

For nearly fifty years, Marlene Dumas has translated the inner tensions of the human psyche into images, distilling them into poetic tableaux that stir raw emotion — attraction, repulsion, fear — and awaken the darker sides of ourselves.

“My brain is a compost heap.

My art a compound expression.

As a magpie collects anything that glitters

as a dung beetle collects everything that stinks,

so my savage joys are brought about.”

— Marlene Dumas

Unflinching in her gaze, she tackles love, death, sex, pornography, gender, motherhood, childhood, war, desire, the passing of time… “universal themes that can appeal to viewers of any generatios, culture, race or and background,” explains Hanna Schouwink, director of the New York branch of the international gallery David Zwirner. In 2010, she exhibited there “Against the Wall”, a monumental series drawing parallels between the Western Wall and the barrier dividing Jerusalem — a symbol of Palestinian oppression. Still haunted by the weight of apartheid, Dumas cannot turn away from injustice or oppression. “Her work stems from a huge generosity, compassion, and a curiosity towards humanity, but also art making and the creative process itself,” Schouwink continues.

No, I don’t consider myself a portraitist in the academic sense of the term.

Marlene Dumas

Her sources of inspiration are wide-ranging. She reinterprets photographs of her family and close circle, images from the press, and material from pornographic magazines. This is a defining element of her work in the 1990s, exemplified by Miss January, a nod to Playboy covers featuring a monthly playmate. Dumas also reimagines well-known figures — Marilyn Monroe, Sigmund Freud’s wife, Dora Maar, Maria Callas, Martin Luther King, Naomi Campbell… — as well as Osama bin Laden and Phil Spector. Every facet of humanity has its place in her work.

Another central figure in her oeuvre is her daughter Helena, who appears at various stages of her life, opening up multiple layers of meaning. In The Painter (1994), nude and with paint-covered hands, the child becomes a kind of alter ego. Among Dumas’s references are also literature — as seen in her illustrations for Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis and Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris — film, from Luis Buñuel and Pier Paolo Pasolini to Scrooged (Fantômes en fête), and art history. In The Particularity of Nakedness (1987), a monumental painting nearly three metres long depicting her partner Jan Andriesse nude, she draws from Hans Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, held at the Kunstmuseum in Basel. High and low culture coexist throughout her work.

She reinterprets photographs of her family and loved ones, images from the press, and material from pornographic magazines. Dumas also reimagines celebrities — Marilyn Monroe, Freud’s wife, Dora Maar, Maria Callas, Martin Luther King, Naomi Campbell… — and Osama bin Laden.

When asked whether portraiture is the core of her practice, she replies: “No, I don’t consider myself a portraitist in the academic sense of the term. And it’s not the only genre I explore. To me, things are more fluid. My portraits of dead people may become still lifes, or my series of blindfolded faces and the works in the exhibition ‘Against the Wall’ might be seen as history painting.” As though painting itself had the power to lift current events out of time and release them from immediacy.

“I use portraiture for very different purposes — primarily to express a point of view, not about the person depicted, but about politics or to generate meaning. The White Disease is not about the source image I started from, but about racism and the harms of white supremacy in general. The portrait of the writer Céline on his deathbed is, through its title The Death of the Author (my titles are an essential part of my works’ content), less about Céline himself than about the notion, as Roland Barthes put it, that ‘the unity of a text lies not in its origin but in its destination’ (La Mort de l’auteur, 1968).”

It is indeed in her studio — working at night, alone, under artificial light — that Marlene Dumas frees herself, reconnects with her instincts, and might well make her own the words of Baudelaire in Le Spleen de Paris (1869), which she illustrated:

“At last! Alone! One can hear only the rumble of a few weary cabs. For a few hours, we shall possess silence, if not rest. At last! The tyranny of the human face has disappeared, and I shall suffer no longer but through myself.” ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Portrait of the artist Marlene Dumas in front of the Louvre, Paris.

Photo © Anton Corbijn, 2025