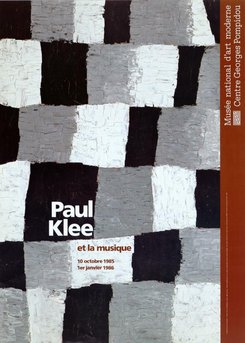

Exhibition

Paul Klee

Irony at Work

�6 Apr - �1 Aug 2016

�6 Apr - �1 Aug 2016

The event is over

Late night opening: Thursdays till 11 pm

The Centre Pompidou offer a new survey of the work of Paul Klee, 47 years after the last big French retrospective at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in 1969. Bringing together around 250 works from major museums around the world, the Zentrum Paul Klee and private collections, this themed retrospective offers a new look at this pioneer of modernism, one of the great figures of 20th-century art.

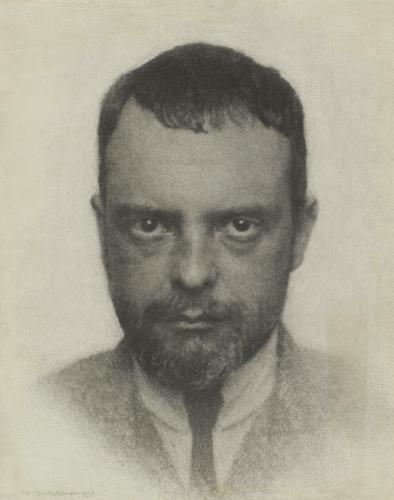

Staging an exhibition of Klee’s work is a challenge: the creator of almost 10,000 works, the unclassifiable artist par excellence, he seems to escape every attempt to pin him down. Characterized by a certain duality, an ambivalence, a mind all oppositions, he presents himself in turn as god and as comedian. The exhibition at the Centre Pompidou takes as its theme “romantic irony’ and its corollaries of satire and parody. Fruit of early German Romanticism, romantic irony denotes the reflexive, self-conscious detachment of the creative process. Klee’s works can thus be understood as a sort of game, an attempt to say the unsayable despite the basic incapacity to do so, the artist exploring the means that art gives him to achieve his ambitions. This approach illuminates Klee’s relationship to his peers and to contemporary art movements, showing how he assimilates or appropriates these influences to his own ends, creating a unique mode of artistic expression.

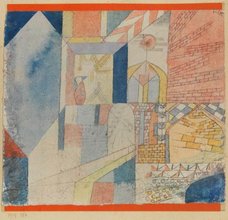

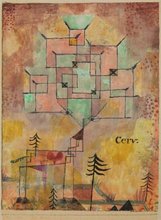

The abstract watercolour Laughing Gothic of 1915, on loan from MoMA, New York, offers a good illustration. If one notes a resemblance to Robert Delaunay’s painting St. Severin 1, Klee seems in his choice of title to be mocking the debates on the psychology of style that were taking place in Germany at that time. Associating the Gothic with laughter to designate a composition inspired by the work of a French Cubist is a way for Klee to mark his detachment.

The exhibition is organised in seven thematic sections that look at the successive stages in Klee’s development as an artist: the satiric beginnings; Cubism; mechanical theatre (in tune with Dada and Surrealism); Constructivism (the years at Bauhaus Dessau); looking backward (the 1930s); Picasso (his reception by Klee after the Zurich Picasso retrospective in 1932); the years of crisis (in the face of Nazism, war and illness). The exhibition brings together paintings, sculptures, drawings and underglass paintings, an outstanding selection of works, half of which have never been shown in France before. Among these rarely-seen masterpieces are two legendary watercolours from Walter Benjamin’s collection: Vorführung des Wunders and Angelus Novus.

"L'ironie à l'oeuvre"

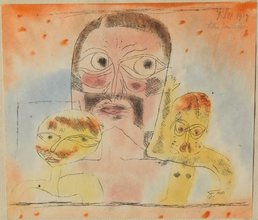

At 22, Paul Klee declared in his diary: “I am God”. Not much later, he wrote in a letter to his fiancée Lily Stumpf: “I now content myself with that lovely thing, self-irony.” This attitude he maintained throughout his life. “He always had a very strong taste for satire, for irony, for all those kinds of unseriousness,” his son Felix would comment later.

Forty-seven years after the last major French retrospective, the exhibition at the Centre Pompidou seeks for the first time to reread Klee’s work as a whole in the light of the Romantic concept of irony. Beginning from a negative and pessimistic assessment of the art of his time, which he thought an exercise in imitation, Klee soon adopted a detached and independent stance that allowed him to overcome this predicament. “I serve beauty by delineating its enemies (caricature, satire)”, he wrote in his diary in 1901. This retrospective brings together some 230 works from the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, from major museums around the world and from private collections. Alongside rarely lent key works, such as Highways and Byways or the late masterpiece Insula Dulcamara, visitors will also be able to see the legendary Angelus Novus. Never before exhibited in France, this oil transfer drawing owes its very particular aura to Walter Benjamin’s discussion of it in the ninth of his Theses on the Concept of History. For the first time since the 1930s, Angelus Novus will hang alongside the other of Klee’s works that Benjamin owned: The Presentation of the Miracle. The exhibition also includes less well-known works by Klee, such as the sculptures, drawings and under-glass paintings of his youth. More than half of the works on display have never before been seen in France.

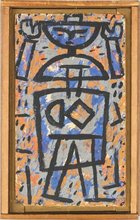

Throughout his life, the artist continued to refine this dialectical strategy, fundamental to romantic irony as an artistic procedure that alternates affirmation and negation, self-creation and self destruction. Klee developed an art that incorporated a reflection on its own means and principles, an art of abstraction and construction. For him, art had to be “a game with the law”, “a flaw in the system”. The exhibition shows how, through the different periods of his life, Klee deployed this irony to denounce the norms and dogmas of the art of his day, from his satirical beginnings to his last years of exile in Bern. A powerful weapon, irony allowed him not only to escape the rules but also to affirm his complete freedom, the foundation of his humanistic idealism. For Pierre Boulez, Klee’s insubordination, his way of simultaneously positing “the principle and its transgression”, was the most important of the lessons he had to teach.

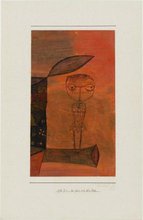

Klee’s artistic beginnings were marked by a bitter disillusion, a “great humiliation” he called it, which prompted him to put his whole work into question. On his journey to Italy after finishing his studies in Munich, he came to realise that he lived “in an age of epigones” (that is, of followers), a thought he found intolerable. Satire then presented itself to Klee as a properly modern means of expression that could unite two different approaches to art and life: on the one hand, the affirmation of elevated, ideal values, and on the other, the adoption of a critical perspective on the state of the world. Klee thus embarked on the production of caricatures – drawn, engraved, or painted under glass – that give expression to his desire to distance himself from the society of the day.

Klee’s encounter with Cubism – in the shape of Picasso and Robert Delaunay – in Munich in late 1911, helped the young artist find the way forward, its Parisian discoveries now guiding his explorations. While drawing on its prismatic vocabulary in childlike drawings, Klee also ironised on the Cubist decomposition of the figure, which robbed it of its vitality. In the series of watercolours produced during his first visit to Tunis, in 1914, he used estrangement effects, such as the way he left unpainted the vertical strips corresponding to the rubber bands he used to hold the paper while painting from life. This distancing is also visible in his very distinctive habit of cutting his compositions into two or more parts on completion, each becoming an autonomous work or finding itself recombined on a new support. In such gestures, Klee affirmed a creative impulse rooted in the act of destruction.

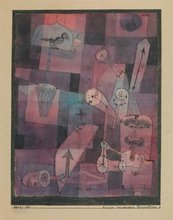

After the war, an imagery of mechanical figures made its appearance in Klee’s work. Inspired by his experiences in the flying corps, he transformed birds into aeroplanes, often in assault formation. The machine aesthetic was in vogue in Dada circles, from Francis Picabia to Raoul Hausmann. Contact with Zurich Dada thus considerably revived Klee’s interest in representations of machinery and equipment and in the effects produced by their mechanics. He created hybrid beings, both human and inanimate. Klee was drawn to the motif of the automaton or marionette not only from admiration for such Romantic authors as Heinrich von Kleist or E.T.A. Hoffmann, but even more so as to denounce, in their mechanical schematization, the loss of vitality and the shrinkage of inner life in the age of industrial rationalisation. “When will the machine give birth?”, he asked. His dreamlike figures attracted the attention of the Surrealists who were just beginning to gather around André Breton, who invited him to join their first group show, at the Galerie Pierre, in Paris in 1925.

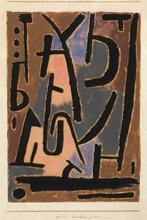

This fascination with technology was felt at the Bauhaus, where Klee taught from 1921, being notably evident in the stylized figurines of Oskar Schlemmer. Walking a tight-rope, Klee sought to maintain an equilibrium between his intuitive approach and the new dogmas of contemporary art. He thus took up certain elements of the modernist idiom, such as the grid, while also undoing its rigidity. His paintings structured by squares can suggest musical rhythms, stained-glass windows, tapestries, multicoloured flowerbeds or fields seen from above. The Bauhaus’s move to the modernising city of Dessau in 1925 reinforced the school’s interest in the optical technologies championed by newly appointed teacher László Moholy-Nagy. Klee responded in his own fashion, the rationalist aesthetic acting as a counter-example that allowed him to assert his contrary position. He reinterpreted Kandinsky’s theory on colour and geometric forms, introduced recumbent bodies into analytic drawings, and used spray painting not to produce impersonal surfaces but to create clownish portraits. According to Klee, “laws should do no more than provide a basis for the possibility of free self-expression.”

Angela Lampe

Source :

in Code Couleur, n°25, may-august 2016, pp. 10-15

Where

Galerie 2

When

�6 Apr - �1 Aug 2016

11am - 9pm, every mondays, wednesdays, fridays, saturdays, sundays�6 Apr - 28 Jul 2016

11am - 11pm, every thursdaysNocturne le jeudi (23h)

Partners

Avec le soutien de

.jpg)

En partenariat média avec