Gilles Aillaud, an eco-artist before his time

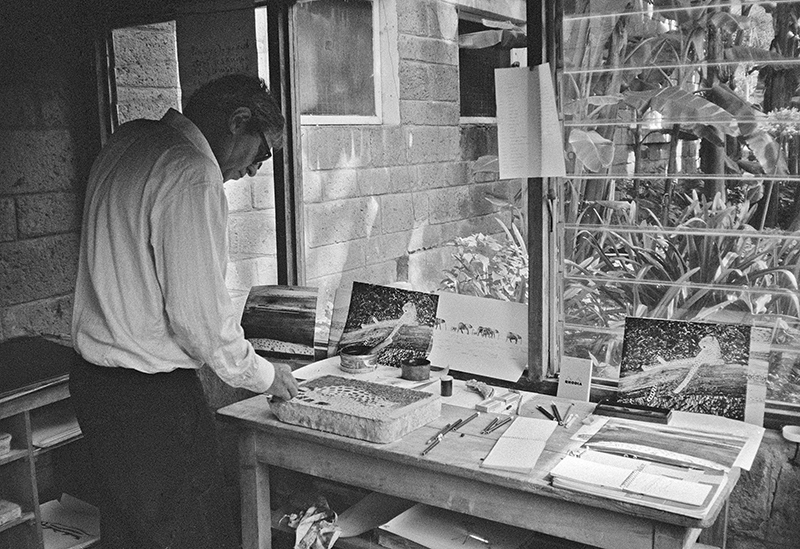

Starting with animals in zoos, more occasionally in open landscapes, as well as minerals, plants, skies, oceans, beaches, soils, mountains, deserts, a few 'humanimal' portraits, and then historical images (May '68, the Vietnam War, etc.), sets and stage designs for the theatre. This is what Gilles Aillaud has represented all his life. Much has been written about this strange creature, a sphinx philosopher and poet, painter of the times, of his own era, as well as of the long term, of an abolished, cosmic time. Despite this, the artist remains as elusive as ever, much like what he observes.

Given the current climate crisis, the sixth mass extinction of species, and social and geopolitical crises, his work is a most relevant response to the looming horror. The artist is a revolutionary, a visionary, an innovator, quite the opposite of what he has sometimes been criticised for. Indeed, Aillaud redefines nothing less than the relationships between human beings and other animals and, more broadly, earthly things.

The artist is a revolutionary, a visionary, an innovator, quite the opposite of what he has sometimes been criticised for. In fact, Aillaud redefines nothing less than the relationships between human beings and other animals and, more broadly, earthly things.

His political commitment is perceptible and operates on several levels. One of the most subtle is to steer his line of flight towards horizontality and a certain equality of consideration of others. Why look at animals? John Berger answered this question in 1980 in his cult eponymous book. We are only just beginning to understand that this is not a peripheral or minor subject and that animals have also been metaphorically confined, reduced to simple symbols in the service of human narcissism. Aillaud contributes in part to getting them out of the cages when he lifts the veil on this ancient and modern 'anthropogenic (or anthropological) machine' and on its corollary, anthropogenesis, identified as such by Giorgio Agamben.

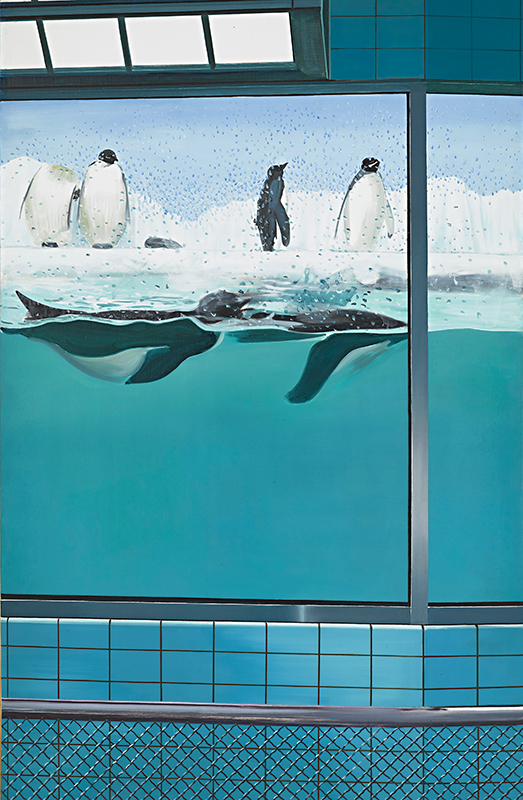

This approach goes hand in hand with the invention of a whole optical device and tools for restraining bodies and minds. Collections of exoticised living animals and modern zoos are human environments created by and for humans. For Aillaud, the cold space of the zoo, with its hygiene policy dating back to Carl Hagenbeck, contrasts dramatically with its organic captives. Furthermore, according to historian Violette Pouillard, these demonstration institutions, panoramas of human power, refer to many sectors of our societies, including entrepreneurial and economic sectors. They are the plural heritage of encyclopaedism, cabinets of curiosities, royal menageries and human zoos, an innovation of hegemonic classes and empires. Their goal was distraction and then the imposition of power (imperial, royal, aristocratic, bourgeois, colonial, supremacist, religious). The story told since the 18th century to justify this violence is rooted in (neo)colonial rule and has evolved as societal changes occur.

By working in zoos, places where, paradoxically, everything is obvious, Aillaud shows us the reality before our eyes that, strangely enough, we would not otherwise see (Aristotle's conception of art): an anatomical theatre of the world, an unnatural history, history of subjection and the system of subalternation, biased encounters, suffering animal individuals.

By working in zoos, places where, paradoxically, everything is obvious, Aillaud shows us the reality before our eyes that, strangely enough, we would not otherwise see (Aristotle's conception of art): an anatomical theatre of the world, an unnatural history, history of subjection and the system of subalternation, biased encounters, suffering animal individuals. He paints "what must be delivered from appearance to appear", as he wrote about Vermeer, but which also applies to his work. He frames, unframes, reframes, scrutinising the situation from both near and far (micro/macro). Despite being confined, the pressure of a life under control (for a long time, animals could not even hide from view), the psychopathologies (zoochosis) to be read in conjunction with Michel Foucault's Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (1961), it sometimes seems that animals are watching us. Yes and no. Attempts at rebellion and escape are plentiful, not to mention deaths and suicides. So how do we escape prison?

Discipline and Punish, Foucault's seminal work of 1975, is like a paving stone in a pond rippling with waves that continue to shake us. For Aillaud, art too is caught up in normative structures and coercive contexts of domination, discipline and power relations. Museology, the history of museums and exhibitions, is written in conjunction with the history of the architecture of zoos and Jeremy Bentham's famous panopticon. The aim is to maximise supervision, to compel the viewer to look through a single perspective or lens, a single framework for reading the world. The history of the visual eye and display is a direct descendant of the history of thought. Aillaud, for his part, proposes painting and art as practices of freedom, rather than liberation (Foucault).

For Aillaud, art too is caught up in normative structures and coercive contexts of domination, discipline and power relations.

Similarly, the responsibility of the artist and the use of one’s own freedom is a central point of reflection for the artist. His painting, which defies figuration and abstraction, is effective, light and non-materialistic, by no means a 'gestural' painting, or even less in the emotionality of the expressionist touch, for example. He gradually strips it of its contours and boundaries, removing the superfluous when he captures animals moving freely during his trip to Africa. Far from the ambient noise and vanity, The Society of the Spectacle (Guy Debord) or the industrialisation of culture and art, he remains faithful to things and beings, to physical existence, to the liquid reality of his time, to what actually counts in the end. With a rare acuity and ethic, he focuses on the essential, wishing to address everyone, not just a select group.

Aillaud speaks of his love for the diversity of forms, exteriority and the beings in worlds. Art only makes sense in the face of this plurality. He rejects globalisation, cultural homogeneity and imperialism. At first glance, his images might appear to be lacking in emotion, but this is not the case. What empathy does it take to see what few see, the animals for whom they are? His work bears witness to his immense, discreet and polite attention to these scorned beings. Aillaud loves them and says so himself. He identifies the similarities between living things, outlining the broad contours of mimicry (Roger Caillois) and painting that dissimilar Same that is so hard to pin down. Some modes of existence are as yet unimaginable. The challenge is to bring them to light, to understand the absolute otherness, the differential between beings (the gap). It is precisely in this unknown, outside the controlled, that Aillaud's artistic experience takes root. This foreign contagion gives rise to the monstrosity and reinvention potential of art, its extraordinary capacity for discovery.

While the artist depicts the interconnection and companionship between living beings, this is also a reflection of what is lacking: the separation, particularly between species and kingdoms, that is characteristic of Western culture.

While the artist depicts the interconnection and companionship between living beings, this is also a reflection of what is lacking: the separation, particularly between species and kingdoms, that is characteristic of Western culture. He portrays the obsolescence of Homo sapiens, of his modernity, of his positivist belief, now transhumanist, in the idea of capitalist progress, the end of a certain human-centred humanism. Instead of fuelling the fragmentation of the world, it promotes its poetization. Far from being an ego artist, he works towards demythification and demystification (Roland Barthes). He was also probably an eco-artist before his time, a posthumanist interested in the in/animate, a curious and creative mind trained in ancient philosophy and the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

In this quantum universe, matter is still radically open. Aillaud knows that forces are first and foremost biological and materialist before they are discursive. So, it's not just a question of painting animals or zoos; art is made of them (and 'nature', physical matter), caught up in them, and agencying with them. Beyond this, Aillaud also speaks of becoming matter, of perpetual metamorphosis, of the dissolution of oneself in the image and the world. Even more so at a time of fear of nuclear weapons and their omnicidal power (which is once again a topical issue). As a wise man, the artist continues to raise a fundamental question: how does art contribute to bringing us closer to the truth and its fundamentally unlimited nature? ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Gilles Aillaud, Rhinocéros, 1979

Huile sur toile, 200 x 300 cm

Centre national des arts plastiques, FNAC 34308

© Adagp, Paris, 2023/Cnap