James Frey: “I use artificial intelligence because I want to write the best book possible.”

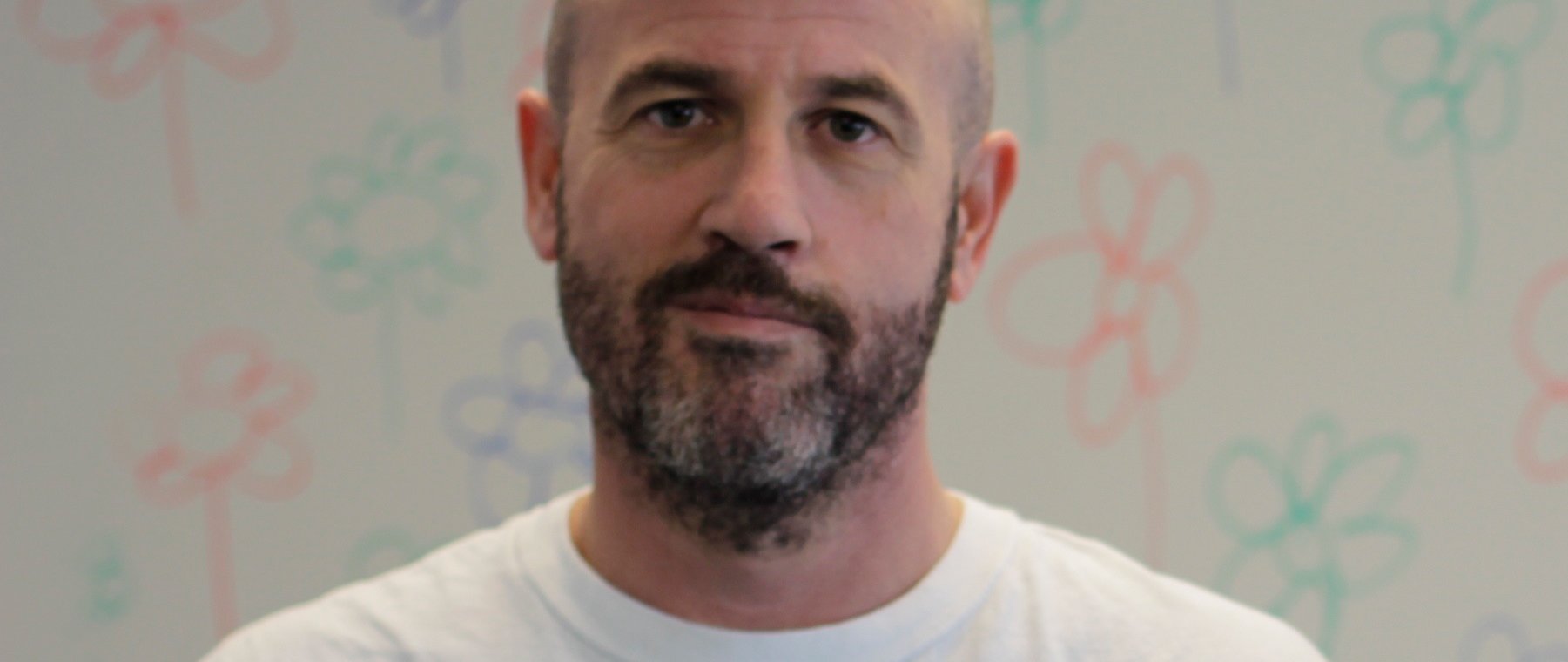

James Frey is on holiday with his children by a lake in Wisconsin. Against this bucolic backdrop, the American writer with shaved head is lost in thought, working his chewing gum vigorously. He strikes the nonchalant attitude of someone who pays no heed to what others might think: writer, rebel, junkie, entrepreneur, subversive, pariah or genius. If the writer triggers such mixed feelings, it is undoubtedly because his arrival twenty years ago on the literary scene caused a stir like no other. Back in 2004, this Bukowski and Henry Miller fan from a good family who fantasised about being an outlaw burst riotously into the literary world with A Million Little Pieces (Doubleday Books), a brutal autobiography describing his struggle with drug addiction and alcoholism in a rehab centre. Hailed as one of the most visceral explorations of addiction, the work was admired by Gus van Sant, Bret Easton Ellis and Pat Conroy who deemed the account the “War and Peace of addiction”. A seismic shock, rarely seen in literature, selling ten million copies worldwide. Then as an investigative website asserted that many parts of his memoirs had been invented, his house of cards came tumbling down. The American media went wild, the author apologised, his agent dropped him, as did his publisher, and lawsuits piled up. Insulted, hunted down, the writer became the first target for what is now known as cancel culture.

Back in 2004, this Bukowski and Henry Miller fan from a good family who fantasised about being an outlaw burst riotously into the literary world with A Million Little Pieces, a brutal autobiography describing his struggle with drug addiction and alcoholism in a rehab centre.

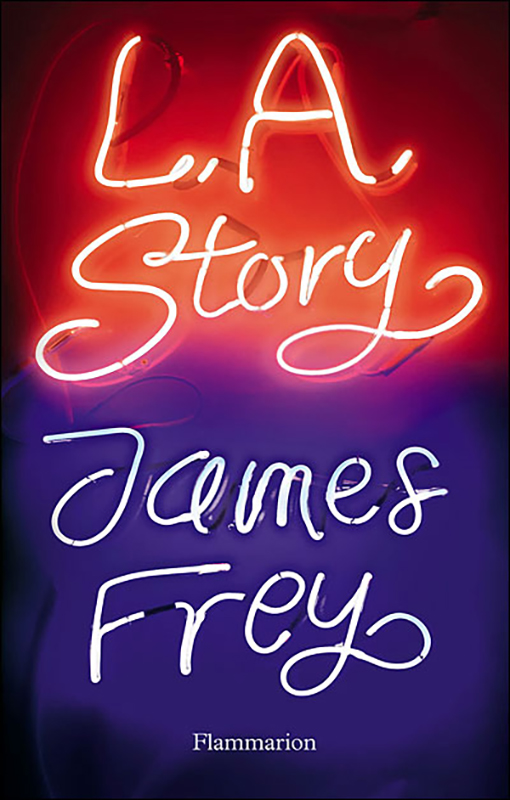

His reputation in tatters, James Frey could have simply disappeared, to become a mere footnote in American literature and an example of marketing strategy gone wrong. But that would be reckoning without his capacity for resilience, as previously demonstrated when he managed to put a decade of addiction behind him without any help from Alcoholics Anonymous. Even after being dragged through the mud as if he had committed the worst of ignominies, the writer gradually built up an offbeat body of literary work, in a unique voice used to joyfully erase literary convention. Between Bright Shiny Morning (HarperCollins, 2008), a powerful account narrated by several characters which captures the very essence of LA; The Final Testament of the Holy Bible (Gagosian Gallery, 2011), a provocative account of the second coming of a bisexual Christ in 21st century New York; and Katarina (John Murray, 2019), recounting the all-consuming passion between a young writer and a model in 1990s Paris, this controversial artist also found the time to reinvent himself as a seasoned businessman.

In 2009, he founded Full Fathom Five, a transmedia production company, which New York Magazine dismissed as a “Fiction Factory”. He managed a set of young authors writing science fiction novels for young adults as well as projects for film, television and even video games. The rebel settled down into middle class yet continued to divide the press and go against the flow of the literary establishment he seems to despise. James Frey has now sold his company to the French group Webedia and has started writing again, with a project that is bound to horrify the purists. Indeed, for his next novel, the 53-year-old writer has decided to leverage artificial intelligence and he is completely open about it. Exclusive interview.

You are currently working on your next book, called FOURSEVENTYSIX. What is it about?

James Frey — The title refers to the date of the fall of the Roman Empire and the book is a kind of autofiction pointing to the current situation in the United States. Its structure is similar to that of Bright Shiny Morning: a combination of historic facts, statistics, fictional accounts and thoughts on key issues currently raging in the country, which I find pretty terrifying. Like the school district in Texas, which decided to close all its schools libraries to convert them into detention centres for badly behaved pupils. I am like a “mirror manufacturer” and this mirror’s reflection is sometimes really ugly; like the weapons culture which has infected the country. Did you know that today, there are 410 million firearms in circulation in the USA? That’s an average of 1.2 weapons per inhabitant, often assault weapons and machine guns.

Why this urge to write about this current chaotic period in US history?

I first started thinking about this book about five years ago. One of my friends earned a master in classic literature from Harvard with a thesis entitled “Why Empires Fall”. He examined the fall of great empires such as Egypt, Greece, Rome, France and Great Britain, noting that they all fell for the same reasons: public debt, the wealth gap and political polarisation. That friend has now become a trader, betting on bad news. He monitors the fall of empires, countries and corporations, he predicts their ruin and cashes in when it happens. Before Trump was elected, this friend reckoned that we would self-destruct within the next 20-25 years. Since Trump and the Covid pandemic, he is now betting on a seven to ten years path. So I’ve obviously been thinking about that a lot, you just need to watch the news to notice that these three issues are ramping up at an ever-faster rate. I’m just a writer holding up a mirror to today’s American society. Thinking that I might influence this trajectory is absurd, I’m more of a lone voice crying in the wilderness. Freedom of expression has been suffocated, our two political parties are leading us straight to disaster and I get the impression that American writers are afraid to tackle the subject.

I’m just a writer holding up a mirror to today’s American society. Thinking that I might influence this trajectory is absurd, I’m more of a lone voice crying in the wilderness.

James Frey

Creating a work of art means experimenting, which is something you’ve always loved to do. Is using artificial intelligence for your project a new form of experimentation for you?

I use AI because I want to write the best book possible, and I’m prepared to use all the tools at my disposal to make it happen. To assess its capacities, I started just playing around with it. I asked AI to write a poem about sushi in the style of Arthur Rimbaud. It spewed a text that discussed raw fish using the same structure and language as in A Season in Hell. Then I wanted to see whether AI could imitate me and asked it to write a story in my own voice about a guy going to Taco Bell. For my new book, I need access to enormous quantities of statistics, demographic and historical data. Previously, I used Google or went to the library, like many other writers. But none of these are as rapid as AI which has phenomenal power.

Aren’t you afraid of this power?

I’m not afraid of the tools that help to improve my work. Yes, I use it to write my book and I’m absolutely open about that. A new thing for me is that I’m now adding footnotes, which I’ve never done before. They are almost another book in their own right, where I comment on what I’m writing. This is what I noted the first time I used AI: “Artificial Intelligence was used in both the research and composition of this book. I have asked the AI to mimic my writing style so you, the reader, will not be able to tell what was written by me and what was generated by the AI. I am also not going to tell you or make any indication of what was written by me and what was generated by the AI. It was I, the writer, who decided what words were put on to the pages of this book, so despite the contributions of the AI, I still consider every word of this book to be mine. And I don’t care if you don’t. »

You see AI as a tool while many artists see it as a threat…

I use AI for help in creating a work of art and I have no problem with it. Who cares whether I found this information in a book, on Google or using AI! And when I use it, it’s not actually for the narrative composition of the book but to include data along the lines of: “There are 756 billionaires in the US, with a total of 5,5 trillion dollars in assets. Seven of the top ten richest people worldwide are American.” When I need this kind of information, AI serves it up at a snap of my fingers. I take its answer, I modify the language, so it looks like I’ve written it and I stick it in the book. And instead of spending all day on research, it takes something like an hour.

Apart from saving time, how does AI make you a better writer?

If I save time, I am more effective and confident. It’s a machine which can provide me with solutions to move my narrative forward. Can this tool harm my writing? I don’t think so. On the contrary, I think it improves it. Incidentally, do we criticize painters who use technology to create their works of art? When they Photoshop a photo then print it on canvas, does that make it a less interesting work than a painting, created by a painter and his brushes? I don’t think so. It’s just a different way of producing art, with the artist remaining in full control of the end product. And I’m doing the same thing. And if people have a problem with that, they can go f*ck themselves.

Do you think AI has the power to destroy art?

Artificial intelligence knows neither want nor need; it’s a cold, objective machine, the most powerful that has ever existed. Its capacity to facilitate the production of art might prompt people to stop using their brains and their souls. Having tested it thoroughly, I don’t think it can take us that far.

What do you think of the screenplay writers and actors strike which is currently paralysing Hollywood?

I am a member of the Writers Guild of America West, I am on strike, and I went to demonstrate in New York. I am in full agreement with the screenplay writers’ and actors’ position. What the studios are proposing is to replace artists with AI, from design through to release. In short, entertainment products entirely generated by machines. But AI is like your car, it needs a driver. Some can drive better than others, in their own way. But laws are needed to protect everyone. If AI is capable of reproducing a writer’s style, you might potentially ask it to write like you, one day when you’re all out of inspiration. In theory it is possible since like much technology, it tracks and copies everything we do. But you can’t plagiarise content produced by AI; you have to modify the text. To use the painting analogy again, what about all these painters who have a studio with assistants creating 85 to 90% of the canvas? The artist comes along to add their unique touch and make it their own work. Look at Andy Warhol, his studio improved his work, you could say it changed the course of art history. Whereas Mark Kostabi did the same and it was a failure. Remember that the tools are only as good as the person using them. I don’t think AI changes anything in the definition of an artist. I am still the author and writing is still difficult even if AI does make life easier. When I work more quickly, I feel much better, less tortured. Maybe the French will hate my process, but I have always thought that France, more than any other country in the world, loves radicality in art.

I don’t think AI changes anything in the definition of an artist. I am still the author and writing is still difficult even if AI does make life easier. When I work more quickly, I feel much better, less tortured.

James Frey

How does France symbolise radicality in art?

Just look at the history of literature and art in general in France: the greatest French artists are not those who respected the rules. They didn’t do what was expected of them, they did exactly the opposite. Arthur Rimbaud, who has definitely had a great influence in my life and how I write, smashed through convention in poetry when he started writing. Baudelaire too, in some fashion. Both were celebrated for their radical stances. I find that the literary scene has become very conservative, much more than painting, film or music, which has not always been the case. Nowadays, artists resist radical change and I think it's plain ridiculous. I am aware that I will be torn to pieces for my choices but it’s not my job to worry about how people will react. My job is to be in the moment, when I write, when I decide what the next word is going to be. My job is to create a narrative that’s as powerful as possible.

How do you explain this undue caution among artists?

The power of social media and herd mentality have led to art becoming more conservative, especially literature. It worries and appals me to see what’s happening on X (formerly Twitter). And social media well reflects the decline of the country: if you want to see disparity of wealth, political polarisation, violence, division and hate, just go on social media. At any rate, I don’t think it has made the world a better or more interesting place.

Do you think that cancel culture is the greatest threat for an artist nowadays, rather than AI ?

The culture of erasure doesn’t worry me. I already weathered that, 20 years ago and yet I’m still writing books. In fact, that period was liberating for me, I was able to move ahead and do what I wanted. In 2005, the die was cast: you either loved or hated what I was doing, and things haven’t really changed since then. As an artist, if you don’t heed what others think, you can give yourself permission to do what you want and free yourself up in the creative process.

When you write, do you think about how readers might react to a particular character or situation?

I’m human, so of course this kind of thing does cross my mind, but I resist the urge to obsess over it. If I gave in to that, I would never manage to write a book. I don’t try to control what my readers think. I know that some will think what I am writing is interesting, others will find it abhorrent and that I have broken a lot of sacred rules.

Do you plan to continue your “collaboration” with AI to write your next books?

I don’t know. It is a very effective tool, but AI doesn’t have the capacity to feel and express human emotions. Ultimately, my work has always been to get into people’s souls, to try to somehow change how they feel, what they think or experience. If AI can help me do that, so much the better. If it can’t, then I won’t use it. I have plans for three different books and AI won’t be crucial to the writing of them. And who can even say what tools will be available in a couple of years’ time?

Despite the ambient pessimism, what gives you hope?

Yes, there is still beauty, love, joy, decency and kindness in this world. But six years ago I would never have imagined what was about to happen. The USA has now crossed a line and there’s no going back. So I’m hoping to settle here in France in the next five years. I come here often, I feel at home here, I lived in Paris when I was 21, and in Beaulieu-sur-Mer in 2005. I have French blood running in my veins, my two grandfathers were from Alsace. I have always loved France, I’m at home here and some of my closest friends are French, like actor Mélanie Laurent. And more than anywhere else, it’s a country where food, life and art are of the utmost importance. This is what matters to me: a life that doesn’t totally hinge on economic and social success. I want to live in peace, in a run-down château in Provence or the southwest. I want to become a grumpy old American who drinks coffee all day long. ◼