Architectural Secrets ► The Centre Pompidou’s metallic 'exoskeleton'

Austrian architect Dietmar Feichtinger, now a leading figure in steel construction, still remembers the moment vividly. It was 1975, he was a teenager visiting Paris, and he happened to pass by the Centre Pompidou construction site. What he saw left a lasting impression: “It felt like a monster—a very gentle monster—rising right in the middle of the city,” he recalls. That jolt of wonder would become a turning point in his life.

What struck him then still holds true today: the building’s structure is strikingly legible. “It speaks to everyone,” he says. For Feichtinger, the magic lies in collaboration. “When a project really works, it becomes impossible to say who’s the architect and who’s the engineer. That’s when the most exciting things happen. And that’s probably why Beaubourg remains such a milestone.”

Behind the Centre Pompidou's iconic exoskeleton stands a name long overshadowed by starchitects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers—that of its third 'father', Irish engineer Peter Rice.

Behind the Centre Pompidou’s (exo)skeleton lies a name long overshadowed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers: that of its third 'father', Irish engineer Peter Rice (1935–1992). A discreet yet pivotal figure, he oversaw the construction on behalf of the engineering firm Ove Arup & Partners. Following his death, one of the many tributes paid to him came from architecture critic Jonathan Glancey, who dubbed him “the James Joyce of civil engineering”, drawing a parallel between Rice’s “poetic inventiveness, his ability to overturn conventional thinking, and his rigorous mathematical and philosophical logic”, and the legendary Irish writer behind the landmark modernist novel Ulysses (1918).

A Giant Meccano Set

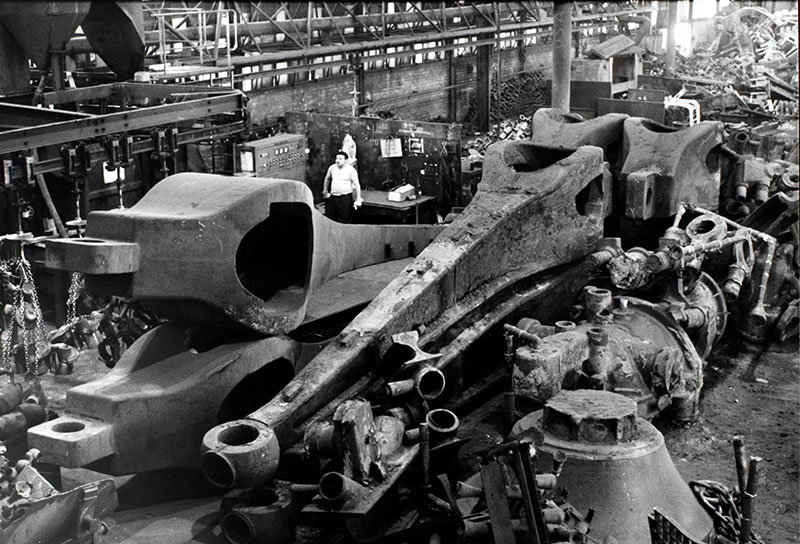

From a structural point of view, building the Centre Pompidou was nothing short of a Herculean task. To hold up the fourteen massive portal frames supporting the museum’s open floors, the architects drew inspiration from 19th-century bridges designed by German engineer Heinrich Gerber (1832–1912). In tribute, the cast-steel joints placed at the intersection of columns and beams were named gerberettes. These elegant, sculptural connectors help redistribute weight across the façade, working in tandem with tension rods anchored to the ground.

It’s a textbook example of architectural coherence—pure and complete. The building lays bare the essential principles of construction: tension, compression, the role of beams… Just looking at it is a lesson in architecture!

Dietmar Feichtinger, architect

The inventory of this architectural giant set is dizzying: 28 columns, each 49 metres tall; 84 beams, stretching 45 metres; and 168 gerberettes, each 8 metres long. Together, the beams and gerberettes alone weigh nearly 8,000 tonnes.

And yet, that’s the brilliance of the design: despite its structural complexity, the building appears light and almost effortless to the casual observer. One last detail—those monumental columns? They’re hollow, and were originally filled with water and glycol, a mixture used to prevent freezing (since replaced in the early 2000s with a special protective coating).

Piano, Rogers, and Rice found here a perfect balance—where structure becomes as much an aesthetic statement as an engineering necessity. Amongst their many sources of inspiration, one stands out and has often been cited: the great Gothic cathedrals of France. At first glance, they may seem worlds apart, yet these sacred landmarks of the 12th century reveal strikingly similar logic: flying buttresses and supporting arches, for instance, were structural solutions that doubled as powerful visual elements—both function and ornament, inseparably intertwined.

Steel, a French Story

Life isn’t all about concrete—there’s room for steel too! Iron and steel run deep in French architectural history, championed by legendary figures like engineer Gustave Eiffel and designer-architect Jean Prouvé, who started out as a metalworker. It was Prouvé who chaired the jury for the Centre Pompidou design competition. When Ove Arup & Partners found out, they jumped in—soon teaming up with British architects Richard and Su Rogers, and later with Italian architect Renzo Piano. The rest is history.

The idea of a complex metal skeleton was the initial premise—never questioned—that guided the winning team’s proposal. It was central to each of their practices at the time, and they all admired the spatial qualities made possible by metal—train stations, covered markets, industrial hangars. It was also a structural necessity for the animated façade (the 'three-dimensional wall') they were envisioning.

Imagine the scandal when the contract to produce the steel components was awarded to the German company Krupp-Stahlbau, which had manufactured weapons for the Third Reich during World War II! French national pride in its steel industry took a serious hit, compounded by a general mistrust of the foreign team of architects and engineers.

To conceal the fact that the beams were coming from the Ruhr Valley, they were delivered under cover of night by oversized convoys. From a railway depot at Porte de la Chapelle, the beams were discreetly transported in pairs to the construction site between 3 and 5 a.m.

To conceal the fact that the beams were coming from the Ruhr Valley, they were delivered under cover of night by oversized convoys. From a railway depot at Porte de la Chapelle, the beams were discreetly transported in pairs to the construction site between 3 and 5 a.m. Thanks to careful planning and flawless execution, the structure was assembled in just nine months, starting in October 1974. Which, in Renzo Piano’s words, “was nothing compared to the scale of the task”.

And Tomorrow?

The Centre Pompidou’s iconic skeleton—like the rest of the building—is entering a five-year renovation phase. When it reopens in 2030, regular visitors shouldn’t expect drastic changes. While the interior of the museum is designed to be in constant flux, any modification to its metal framework is far more delicate and demands expert craftsmanship.

Nicolas Moreau, architect and founder of the agency Moreau Kusunoki (lead architect and principal designer of the cultural component), recalls Renzo Piano’s poetic metaphor: “He used to say that the structure of Beaubourg is like a big horse. If you hang something on it that bothers it, it will shake it off—and it will fall.”

That’s exactly what happened when Moreau Kusunoki began work on the 2025–2030 renovation project. As Nicolas Moreau puts it: “When we started developing the project at the studio, some of our ideas were rejected by the structure itself. The steel skeleton of the Centre Pompidou is like a giant machine—it sets its own rhythm for everything around it.” ◼

Related articles

The future Centre Pompidou’s structure, circa 1975

© Centre Pompidou Archives

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/8/csm_chenille-vignette_braun_ccc5d5c183.jpg)