Focus on... "An Andalusian Dog", by Luis Buñuel

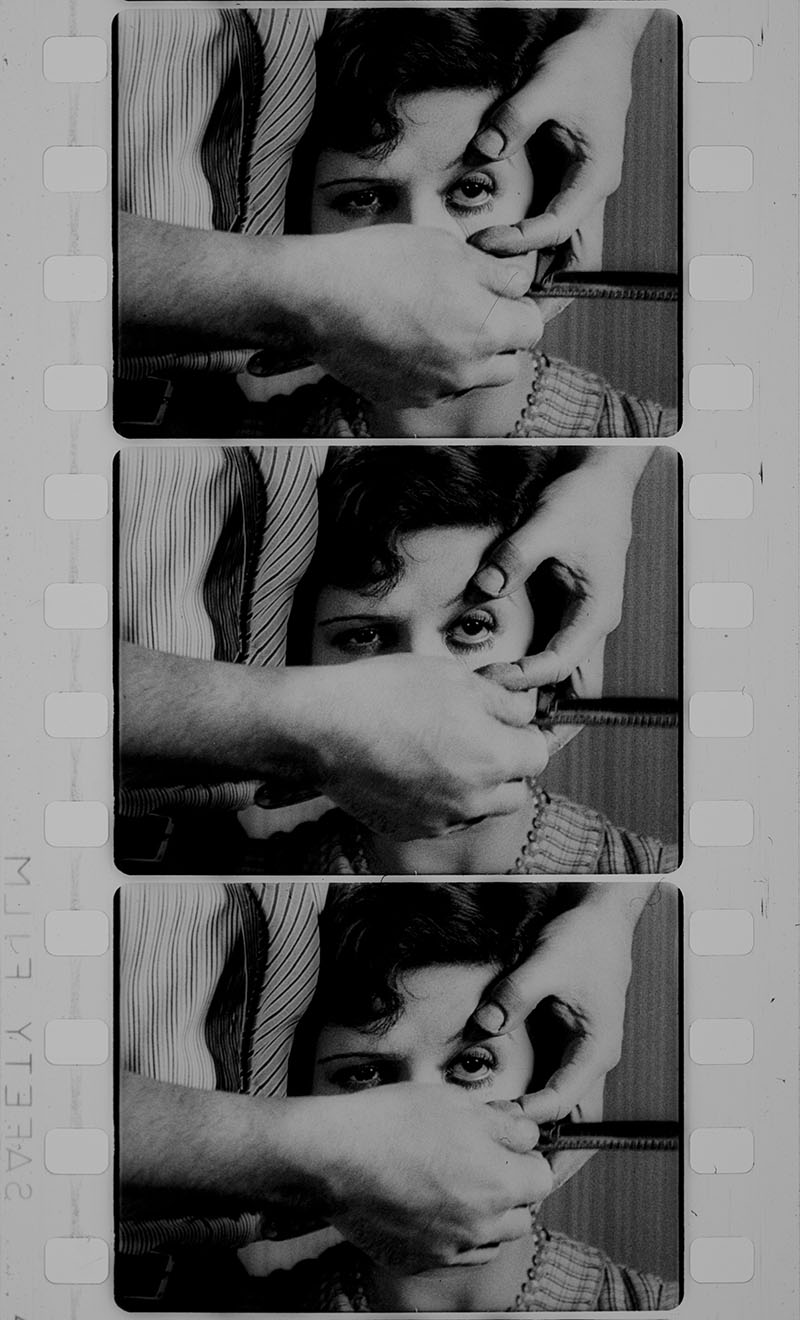

The most celebrated film in surrealist history was born by chance from a casual conversation between two friends. Luis Buñuel was spending a few days in Cadaqués as Salvador Dalí’s guest during the Christmas holidays of 1928. At that moment, these two future giants of 20th-century art were still complete unknowns, their friendship dating back to their student days in Madrid. Buñuel later recounted: “Dalí told me, ‘Last night, I dreamed that ants were swarming in my hand.’ And I replied, ‘Well, I dreamed that someone’s eye was being slit open.’” The idea for Un Chien Andalou was born.

The script was written in six days, the length of their holiday. This montage of dreamlike sequences, assembled without any conscious intervention from its authors, opened the doors of Surrealism to cinema.

The script was written in six days, the length of their holiday. This montage of dreamlike sequences, assembled without any conscious intervention from its authors, opened the doors of Surrealism to cinema. “Dalí and I, while working on the script of Un Chien Andalou, practised a sort of automatic writing—we were Surrealists without the label,” Buñuel recalled. Returning to Paris with his script, he shot the film in about fifteen days in March 1929, with the seaside sequence filmed in Le Havre.

Buñuel’s introduction to André Breton’s Surrealist group came in late June 1929, thanks to Fernand Léger, who introduced him to Man Ray. The latter was looking for a companion piece for his own film, The Mystery of the Château de Dé, commissioned by Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles to document their newly built home in Hyères, designed by Robert Mallet-Stevens.

Un Chien Andalou, already screening since 6 June at the Studio des Ursulines in Paris, seemed a good fit. However, since the film had been labelled ‘Surrealist’, Breton and his circle—ever protective of the term—approached the screening with deep suspicion. This led to a mutual atmosphere of distrust when the Surrealists attended the projection.

During the screening, Buñuel stood behind the screen, providing live sound effects with a mix of paso dobles and excerpts from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. He later claimed he had filled his pockets with stones, ready to hurl at the Surrealists if they rejected his film. But the reaction was unanimously enthusiastic—Buñuel was immediately embraced as the group’s ‘official’ filmmaker.

During the screening Buñuel had filled his pockets with stones, ready to hurl at the Surrealists if they rejected his film. But the reaction was unanimously enthusiastic.

The film’s impact extended far beyond Surrealist circles. From 1 October 1929, it ran for eight months, causing fainting spells, miscarriages, and between thirty and fifty police complaints, depending on the account. The scandal delighted the Surrealists, who saw provocation as a weapon, but they were far less pleased by the film’s mainstream success. In a strikingly contradictory statement published in Mirador on 29 October 1929, Buñuel and Dalí expressed their outrage: “Un Chien Andalou has enjoyed an unprecedented success in Paris; something that fills us with indignation, like any other public success. We believe that the audience applauding Un Chien Andalou is made up of people stupefied by avant-garde magazines and ‘cultural’ trends, who applaud anything that seems new and bizarre out of sheer snobbery. This audience has completely failed to grasp the film’s moral essence, which is directed against them with total violence and cruelty.”

Despite their denunciation, Un Chien Andalou became legendary. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Photogramme du film Un chien andalou, de Luis Buñuel (1929)

© Héritiers Buñuel

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci/Dist. GrandPalaisRmn