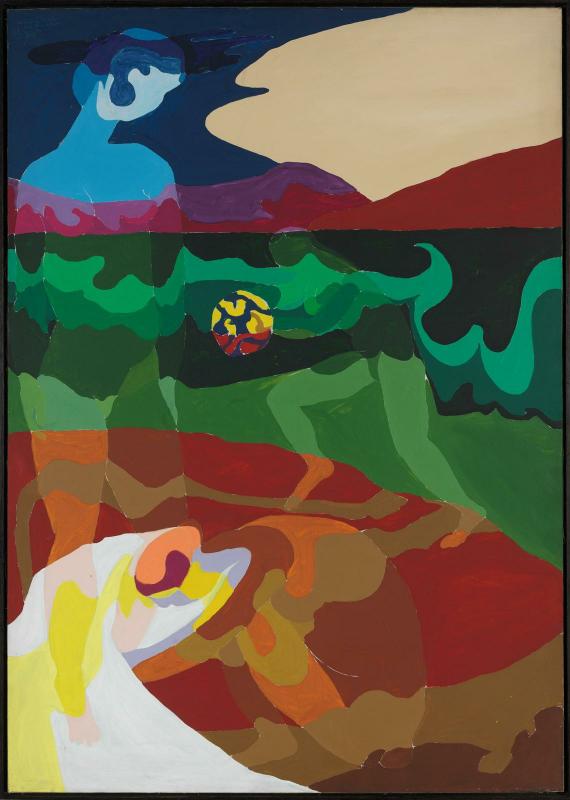

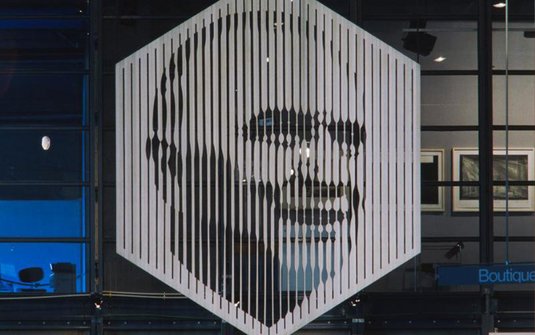

Focus sur... « Camouflage H. Matisse Luxe, Calme et Volupté » d'Alain Jacquet

In 1962, at just twenty-three, Alain Jacquet set in motion the first major series of his career – one of the most striking of its time: the Camouflages. Over the next two years, this sweeping group of paintings would revolve around a single idea: concealing a pre-existing image in plain sight. What he chose to mask varied. A Renaissance or modern master – Paolo Uccello, Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian. Or an emblem of popular culture: the Statue of Liberty, a Disney character, an advertisement. The strategy shifted, too. Jacquet might borrow the familiar pattern of military camouflage, or layer one image over another.

Alain Jacquet began with an imperfect copy of Matisse’s canvas, then overlaid it with a camouflage pattern. The shifting colours of that pattern closely mirrored the chromatic range of the original background.

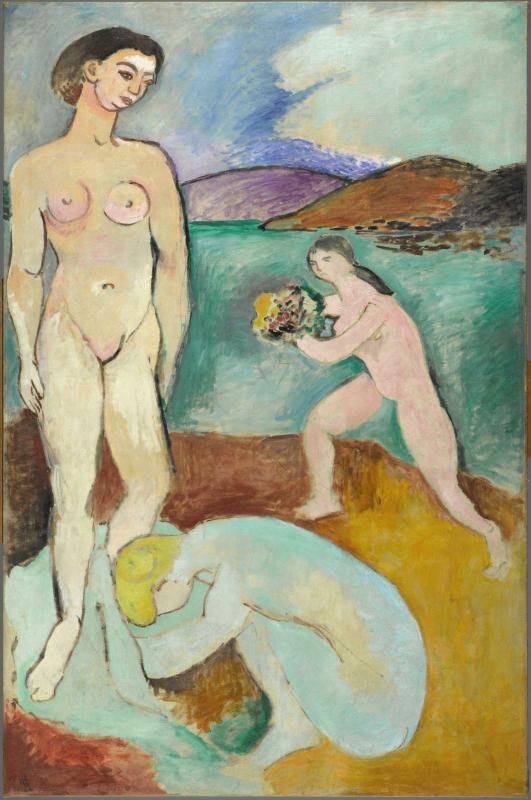

In the spring of 1963, Jacquet turned his attention to one of Matisse’s best-known paintings, Le Luxe I (1907) – a work that, like his own, belongs to the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne. Keeping almost exactly to the original scale (210 × 138 cm), he began with an imperfect copy of Matisse’s canvas, then overlaid it with a camouflage pattern. The shifting colours of that pattern closely mirrored the chromatic range of the original background.

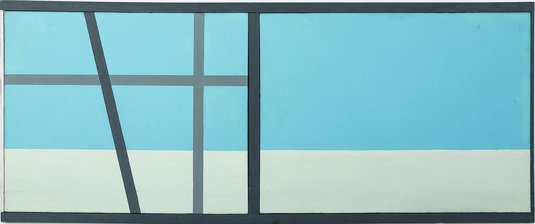

Since camouflage as a visual motif was established in France during the First World War by the Cubist-affiliated painter André Mare (1885–1932), its use to conceal an early twentieth-century painting is not without precedent. When Jacquet began producing his first Camouflages, Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), across the Atlantic, had started reproducing paintings by Paul Cézanne, Mondrian and Picasso using his signature Ben-Day dots. Yet the deliberately handcrafted quality of Jacquet’s Camouflages sets them apart from Lichtenstein’s output and from American Pop art more broadly. Keen to underscore that distinction, Jacquet soon turned to Pop works themselves, camouflaging pieces by Jasper Johns, Robert Indiana and Lichtenstein. He even went so far as to camouflage Lichtenstein’s reproduction of Picasso’s Femme assise dans un fauteuil.

An iconoclastic gesture toward the defenders of a classical or established art—or a way of preserving Matisse from the fate assigned to him by the culture industry and the society of the spectacle?

By covering up a painting by Matisse—or by any other master of the not-so-distant past—Jacquet can seem to strike an iconoclastic pose, challenging the defenders of established classical art. Yet the move is far from a simple act of defiance. Camouflage, it bears remembering, was originally designed not to destroy but to protect: to preserve by keeping out of sight. What if Jacquet’s intent was precisely that—to shelter Matisse from a cultural industry and a society of the spectacle that were, at the time, rapidly gaining ground?

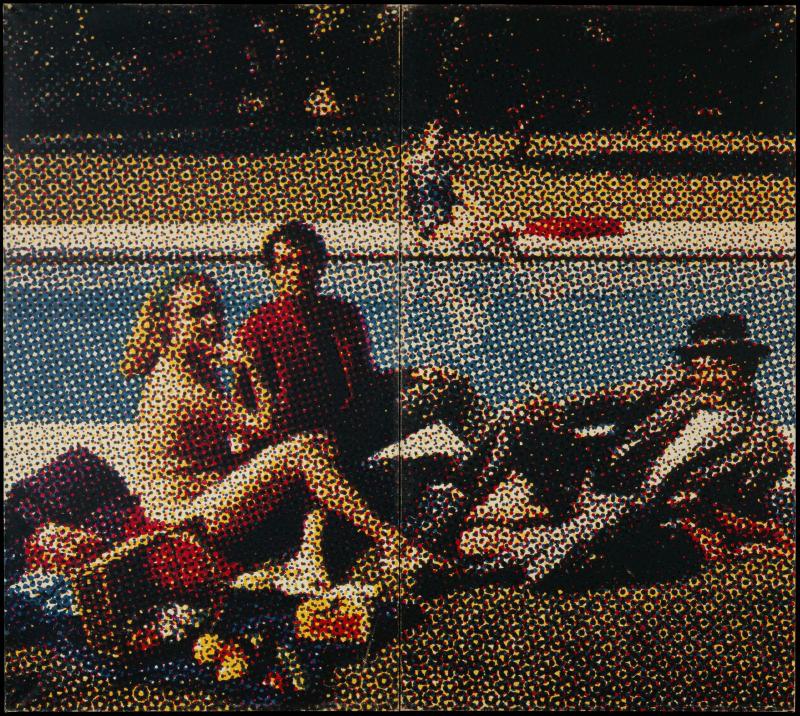

The Camouflages would soon be followed by the Trames, culminating in the celebrated Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1964), also held in the Centre Pompidou’s collection—one of the high points of Mec’ Art (short for mechanical art) and of European Pop art. ◼

Related articles

Alain Jacquet, Camouflage H. Matisse Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1963 (détail)

Huile sur toile, 203 × 144 cm

© Centre Pompidou / photo : G. Meguerditchian / Dist. Rmn-Gp / Adagp