Jean Widmer: An Avant-Garde of Posters for the Centre Pompidou

In the late 1960s, industrial design was still fighting for cultural legitimacy. In 1969, the Union des arts décoratifs responded by founding the Centre de création industrielle (Cci; see box below), driven by François Mathey—an influential curator and staunch champion of modernity—and François Barré, a senior civil servant determined to see design and architecture recognised as cultural disciplines in their own right.

Conceived as a laboratory rather than a museum, the Cci set out to show design, architecture, and industrial innovation not as neutral tools, but as practices shaped by aesthetic, social, and political choices. Its inaugural exhibition, “Qu’est-ce que le design ?” (What Is Design?), set the tone from the outset, placing meaning and responsibility at the heart of the design debate.

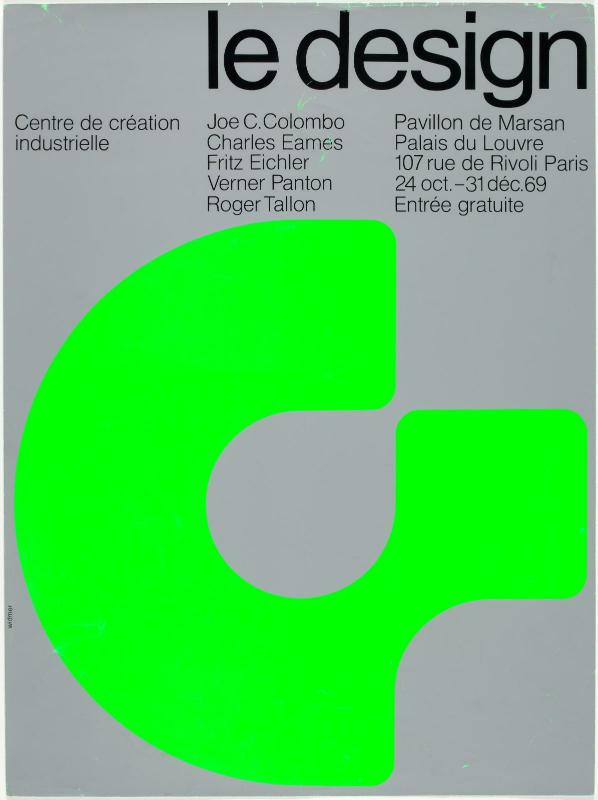

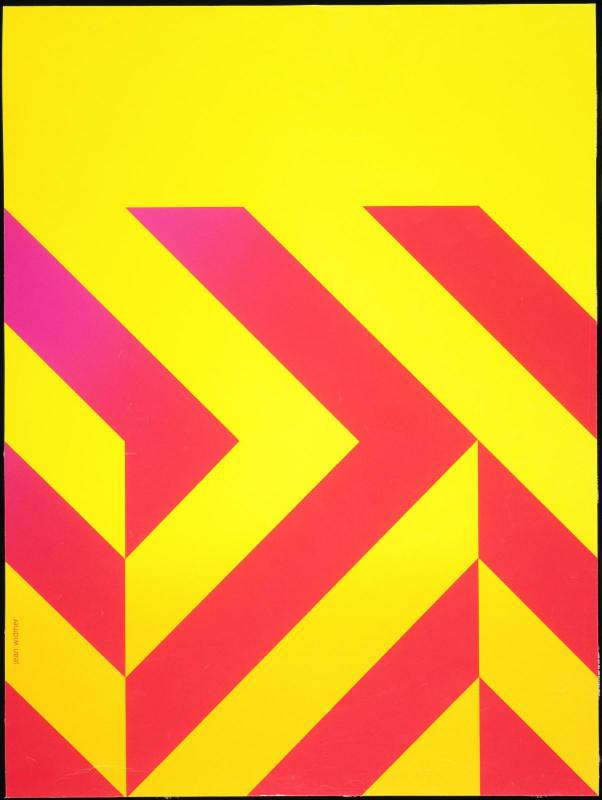

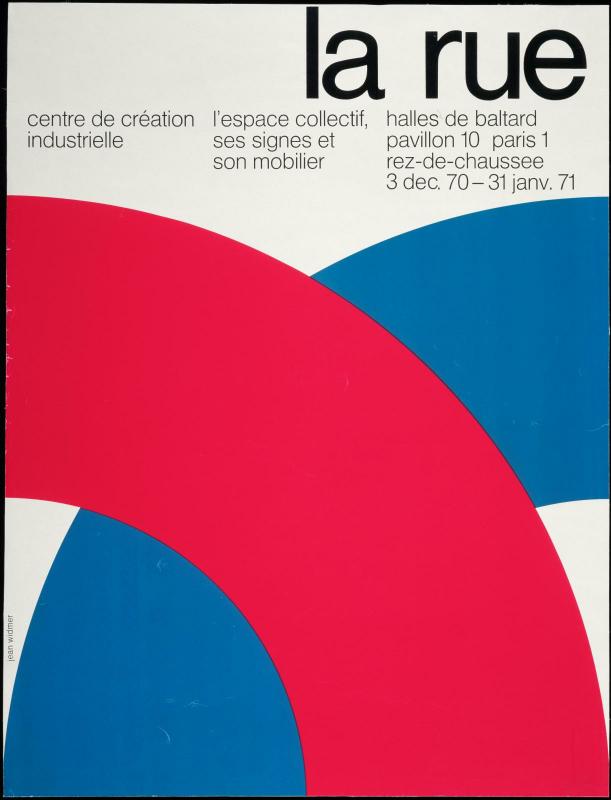

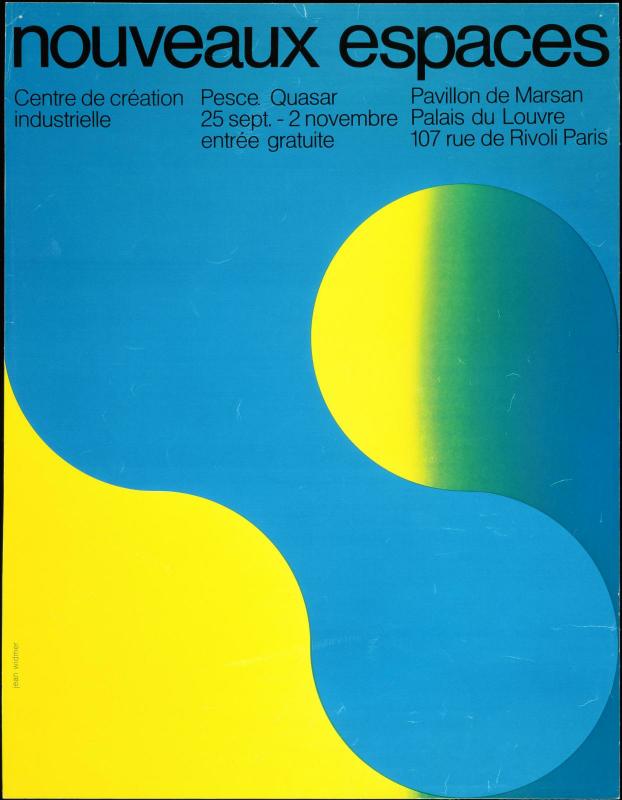

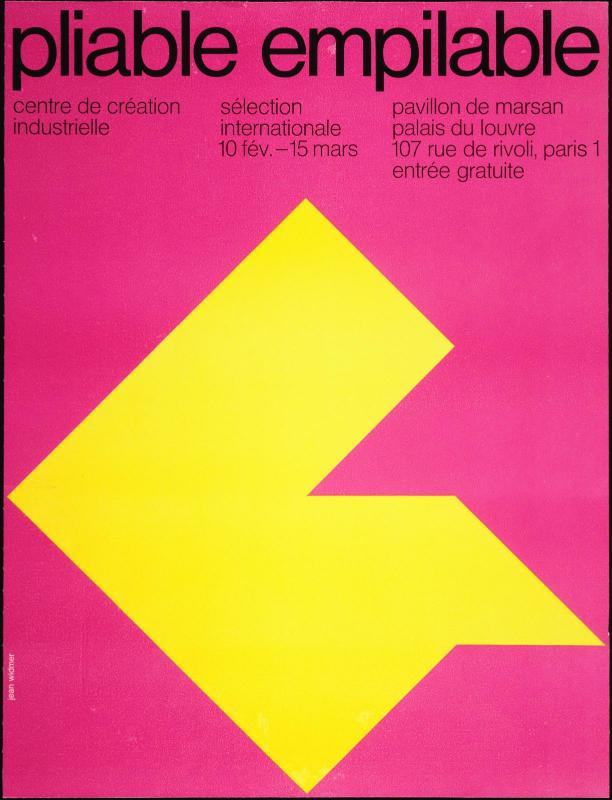

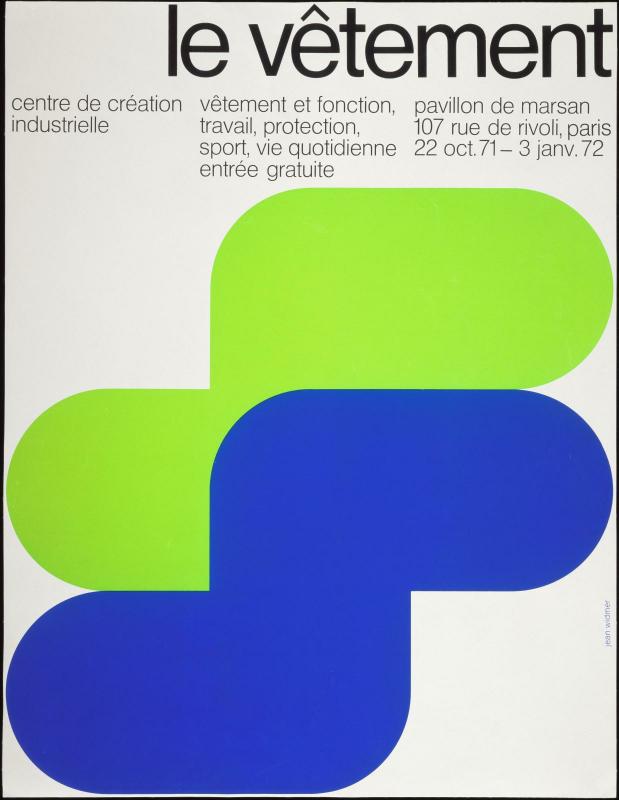

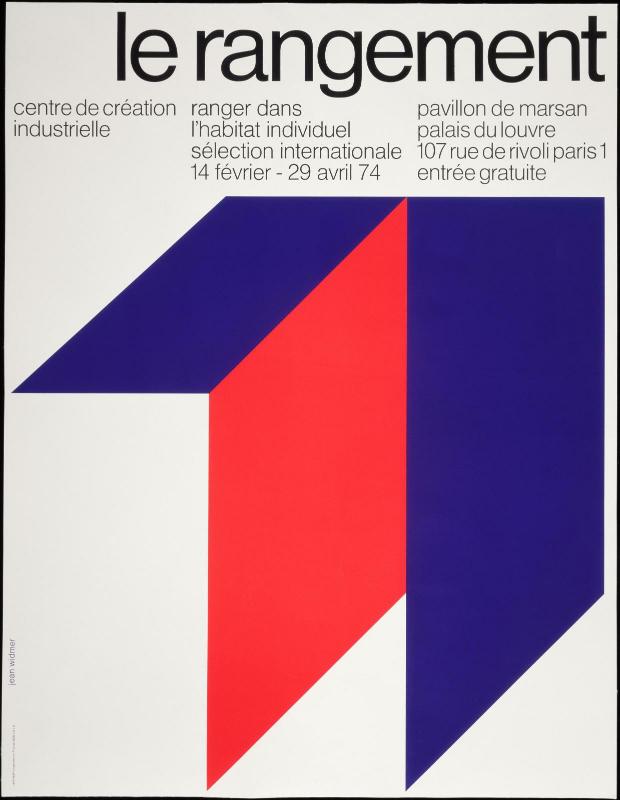

With “Qu’est-ce que le design ?”, the first of twenty-one posters, Widmer introduced a graphic system he would refine over the years. The rule was absolute: text at the top, image below. Geometric forms. A stripped-back palette. No effects.

To match this ambition, François Barré turned to Jean Widmer. From 1969 on, Widmer was entrusted with the Cci’s exhibition posters. The brief went far beyond visibility. What was at stake was the visual articulation of a new intellectual project—one still largely unknown to the wider public.

Widmer answered with disciplined radicalism. With “Qu’est-ce que le design ?”, the first of twenty-one posters, he introduced a graphic system he would refine over the years. The rule was absolute: text at the top, image below. Geometric forms. A stripped-back palette. No effects. The poster was no longer illustrative or promotional. It became a conceptual object in its own right.

In a landscape where exhibition posters still largely relied on reproducing the works or objects on display, Widmer’s gesture marked a clear rupture. He rejected all documentary imagery – even when exhibitions brought together major figures of international design such as Charles Eames, Joe Colombo, Verner Panton, or Roger Tallon. Instead, he devised an original graphic composition for each exhibition, conceived as a symbolic translation of its theme.

Widmer claimed a practice of basic design, grounded in reduction, coherence, and legibility. Every form, every colour, every proportion carried meaning.

This minimalism was anything but decorative. Widmer claimed a practice of basic design, grounded in reduction, coherence, and legibility. Every form, every colour, every proportion carried meaning. The poster became an intellectual tool as much as an institutional sign, perfectly aligned with the Cci’s mission: to shift the way design was perceived, from a collection of objects to a field of reflection.

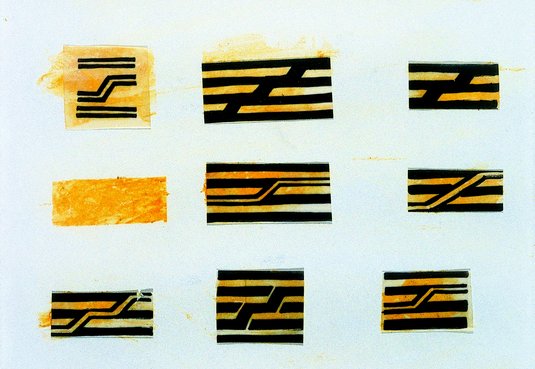

This sustained body of work played a decisive role in establishing the Cci’s visual identity and in securing design’s recognition as a cultural subject. It also represents a crucial milestone in Jean Widmer’s career, well before he would design, in 1977, the now-famous striped logo of the Centre Pompidou. With the Cci posters, Widmer asserted a demanding graphic modernity, in which radicality emerged from the refusal of the superfluous. ◼

The Cci: Bringing Design into the Centre Pompidou

Founded in 1969 within the Union des arts décoratifs by François Mathey, François Barré, Yolande Amic, and Yvonne Brunhammer, the Centre de création industrielle (Cci) was conceived as a laboratory. Its ambition was to establish design, architecture, and industrial innovation as fully fledged cultural subjects.

In 1977, when the Centre Pompidou opened, the Cci was integrated into the institution. Its activities then formed the foundation of the design department of the Musée national d’art moderne, playing a decisive role in the institutional recognition of design in France. In 1992, the Cci and the Mnam merged.

Related articles

Jean Widmer, poster Paris construit, 1970

© Centre Pompidou

© Adagp