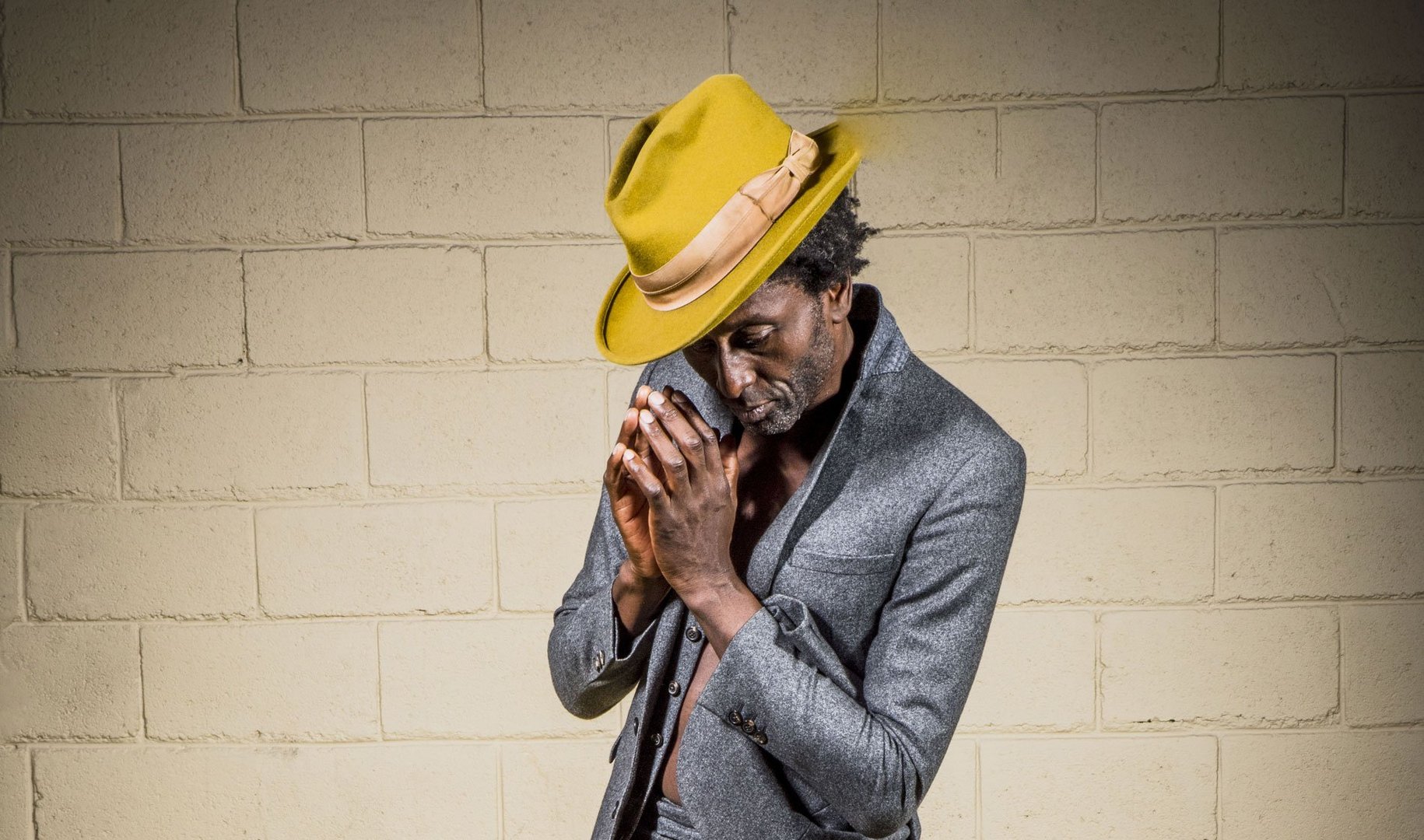

Keziah Jones: "My world is nothing but contradictions and paradoxes."

He arrives perched on a Dutch bike, as lean and tall as he is. His posture is proud, and his suit—a three-piece wool number—is worn shirtless. A wide-brimmed hat tops off the silhouette of a natural-born dandy. At 52, Keziah Jones still looks very much like the wiry musician charged with the raw energy of blues and funk that audiences first discovered in the early 1990s with his hit Rhythm Is Love.

These days*, the Nigerian artist is back in Paris—his adopted city ever since he was famously spotted, as legend has it, playing in the corridors of the métro. Keziah Jones: “I come to the capital often—my label is based here. I know the neighbourhoods well; I’ve biked through them countless times. I remember playing on the Piazza at the Centre Pompidou—it must have been around 1990 or 1991…”

On 9 July, Keziah Jones will be the guest of honour at the Centre Pompidou for an exceptional concert titled Symposiums of the Future. He’ll be joined by dancers Qudus Onikeku and Bukunmi Olukitibi, artist Native Maqari, and filmmaker Simon Rouby—fellow creatives with whom he shares a history, notably Native Maqari, with whom he collaborated on Captain Rugged, a graphic novel exploring the economic boom of 1970s Lagos, Nigeria’s capital (published in 2014).

Symposiums of the Future is a performance shaped as a dialogue—a collective exploration of the layered, shifting definitions of what we call “identity.” Hovering over the entire project is the towering figure of Fela Kuti, a guiding force for Keziah Jones. Born Olufemi Sanyaolu, Jones grew up in Nigeria before moving to the UK. His parents, part of the country’s emerging middle class (his father was an engineer), sent him abroad for his education: “I was eight, wearing a tag around my neck with my name on it in the plane... I was flying to a country I knew nothing about—another culture, another language. I’d packed a Fela record with me. It was No Agreement (released in 1977). Fela is fundamental to me. He took a similar journey when he was young. His music guided me through my own spiritual journey.”

The title Symposiums of the Future is itself a tribute, lifted from a now-iconic 1968 interview with Fela—a clear nod to the Afrobeat pioneer: “Fela is someone to look up to, even if the times have changed. Back then, Nigeria had just gained independence, and the world leaned far more to the left than it does today… But there are still parallels between our eras. He’s a role model—he laid out a path for us.”

From the very beginning, Keziah Jones has brought a political charge to both his lyrics and his genre-blending sound—drawing from West African rhythms, soul, funk, and blues to question the figure of the Black man in the Western world. One of his most acclaimed albums, Black Orpheus (2003), was a nod to Orfeu Negro, the Palme d’Or–winning film by Marcel Camus (1959).

After years of roaming and a long spell in London, Jones settled in Lagos eight years ago—the throbbing heart of Nigeria’s creative scene. During lockdown, he dove into his studio and began working on a new album—some tracks of which he’ll be previewing live on stage this 9 July. “The music I make today is quite different from what I used to create... maybe less tormented. Definitely more instrumental, more shaped by jazz forms,” reflects Keziah Jones.

In Nigeria, recent months have been marked by violent clashes between youth and police, set against a backdrop of political unrest—a context that inevitably left its mark: “We’re living through a unique moment... I’m trying to focus on the body—the body as a political object. I truly believe in the power of sound,” says the musician, taking on the tone of a prophet.

After gaining independence in 1960, Nigeria emerged as an economic beacon before crashing hard in the 1980s. Today, it remains one of Africa’s wealthiest nations—driven largely by oil and a booming population of 219 million, the majority under the age of 25. In Lagos, the artistic scene is vibrant, effervescent—pulsing with raw energy and producing global stars like Wizkid and Burna Boy, leading figures in the afrobeats wave currently sweeping across borders.

“My nephews and niece are huge fans of those artists. They’ve cleverly capitalised on the term afrobeat, coined by Fela, and turned it into this slick marketing concept. The sound is more urban, more electronic, heavily shaped by American formats—it’s music made for the masses... And that’s exactly what Fela’s music was, in the end.”

Today, after seven albums, Keziah Jones remains better known internationally than in his own country: “France has been generous to me—just as it was to artists like Richard Wright or James Baldwin in the 1950s and ’60s, or to African musicians in the 1980s.”

Like Keziah Jones, the current French president hasn’t overlooked the France–Nigeria connection. In 2018, Emmanuel Macron—who knows the country well, having interned at the French embassy in Abuja in 2002 during his time at the ÉNA—visited the Shrine, Fela’s legendary Lagos club, at the invitation of Femi Kuti, the late icon’s son.

“In Nigeria, it was huge that a French president would visit such a symbolic place!” says Keziah Jones with enthusiasm.

“You have to understand—until recently, Fela wasn’t acknowledged by Nigeria’s leaders. To them, he was just a troublemaker... But since his death (in 1997), politicians now lay claim to his legacy, saying they used to frequent the Shrine back in the ’70s, and so on. But no one said that at the time! Fela was far too radical. He was a figure who couldn’t be boxed in, someone who used his music to serve the people—a cause far greater than himself. For people of my generation, the struggle is different, but the tools are the same: we use music and art to awaken consciousness.”

Activist musician, inveterate globe-trotter, aesthete and subway poet—Keziah Jones is all of the above: “My world is nothing but contradictions and paradoxes. I welcome contradiction with open arms! I know exactly how to blend contrasts—that’s something we’ve been doing in Nigeria for a long time.

On my father’s side, the family is Muslim; on my mother’s, Christian. At home, we spoke both English and Yoruba… You have to find the mix that suits you. That’s what I try to do in my music. And in life.” ◼

*Interview conducted in 2021, on the occasion of the concert Symposiums of the Future.

Related articles

In the calendar

Portrait of artist Keziah Jones, June 2021, Centre Pompidou

© Jean-Michel Sicot