Matisse, les couleurs du décor

Proposing a new way of living – and sharing it as widely as possible. Opening art up to everyday practices: architecture, painting, sculpture, metalwork, ceramics, glass. And fostering collaboration across disciplines. This was the ideal embraced by modern artists, architects and designers in the early years of the 20th century.

In his work, Henri Matisse spoke of shaping “a space for the mind” – empty like a room in an apartment, as comforting as a good armchair, as immediate as a bouquet of flowers in an interior – one that would spread “joy through colour”. The rupture he introduced in painting was unfolding at the same moment among architects and decorators of his generation. Together, they began to imagine a new kind of interior: rational in its structure, sensorial in its effect, designed for those who would actually live in it.

Colour, space, mathematical proportion – these are the terms that run through Matisse’s thinking. In his work, as in that of Francis Jourdain, Eileen Gray, or Robert Mallet-Stevens, painting and design aim for what Le Corbusier famously described as images the eye reads as thought. What emerges is a “sensory rhythm”: the shared language of modern creation.

In Matisse's work, as in that of Francis Jourdain, Eileen Gray, or Robert Mallet-Stevens, painting and design aim for what Le Corbusier famously described as images the eye reads as thought. What emerges is a “sensory rhythm”: the shared language of modern creation.

From the late 19th century onwards, architects, designers and artists began working side by side in salons and exhibitions. The most radical figures of the time crossed paths there – from Francis Jourdain to Georges Seurat, from Le Corbusier to Henri Matisse. Out of these encounters emerged the defining lines of a modern decorative movement, shaped through constant dialogue with the European scene.

Across industrial Europe, exhibitions and publications multiplied, seeking to define the new foundations on which to build the living environment of a world shaped by the omnipresence of the machine. At the intersection of art and industry, the decorative arts lay at the heart of the debate among industrial nations, seen as a key means of asserting both economic strength and symbolic power.

Modernity was reshaped around the idea of “social art”. Artists, architects, designers, critics and historians came together in response to a shared aspiration for engaged art. The galleries of Siegfried Bing (“L’Art nouveau”, 1895) and Julius Meier-Graefe (“La Maison moderne”, 1899) were among the first to invite Parisian visitors into fully reconstructed interiors – featuring furniture by Henri Van de Velde, plates painted by Édouard Vuillard, and paintings by Georges Seurat, Maurice Denis or Paul Ranson.

In 1901, a society named “L’Art pour Tous” [Art for All] was founded, with the participation of Roger Marx and Frantz Jourdain, the future founder of the Salon d’Automne in 1903. Architects Henri Sauvage and Charles Plumet, together with the young painter and designer Francis Jourdain, later joined forces within the movement of “L’Art dans Tout” [Art in Everything].

Against the fashionable tide of historicist eclecticism, architects, designers and artists set out to reinvent the very notion of ornament. Their aim was to uncover the immutable founding rules governing the production of form. From the mid-19th century onwards, combining mastery of drawing, theoretical reflection and encyclopaedic knowledge, Owen Jones published The Grammar of Ornament (London, 1856; Paris, 1865). The writings of the French theorist Charles Blanc – La Grammaire des Arts du dessin (Paris, 1860–1867) and La Grammaire des Arts décoratifs (Paris, 1882) – along with Eugène Grasset’s Méthode de composition ornementale (Paris, 1910), played a decisive role in this search for origins.

What they discovered was what Jules Michelet described in La Bible de l’humanité (1864) as an “eternal art, foreign to all fashion, older and newer than our own (old at birth)”. This art revealed itself in Indian craft traditions, presented at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, and later in the Islamic arts from what was then called “the Orient”. Western creators seized upon these simple geometric and chromatic elements, endlessly recombinable, “in accordance with the laws which regulate the distribution of form in nature” (Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament, 1856).

As decorator of the Crystal Palace in 1851, Jones drew inspiration from the ornamentation of the Alhambra and placed colour at the heart of his approach. As critic Lothar Büchner observed that same year: “I had the impression that the raw material with which architecture works was completely dissolved by colour. The building is not decorated by colour, but built by colour.”

Throughout the 1890s, exhibitions of Islamic art multiplied in Paris, culminating in the presentation held in 1903 at the Pavillon de Marsan.

In 1910, Matisse visited the major exhibition of “art mahometan” in Munich. Looking back, he would later recall in an interview with the art critic Jacques Guenne: “I felt a passion for colour awakening within me.”

In 1910, Matisse visited the major exhibition of “art mahometan” in Munich. Looking back, he would later recall in an interview with the art critic Jacques Guenne: “I felt a passion for colour awakening within me.”

That same year, travelling through Germany, Le Corbusier attended the Secession exhibition in Berlin, where he noted that there were “two works” by Matisse – including Marguerite au chat noir [Marguerite with a Black Cat] – that appealed to him, “because of their beautiful colour, their synthesis.”

During the winter of 1911 and the spring of 1912, the painter settled in Tangier, while the architect embarked on his own journey to the Orient.

Colour had become a key instrument of modern rationalism. In 1896, Frantz Jourdain invited architects Henri Sauvage, François Garas and Henri Provensal to the gallery Le Barc de Boutteville, a space devoted to post-Impressionist and Nabi painting. The exhibition he organised, titled “Impression d’architectes”, presented no built projects, but instead spaces shaped by intense colour.

Early rationalist architects, such as Auguste Perret, indeed experimented with the colour of construction materials and pared back decorative motifs, favouring clarity, structure and chromatic force over ornament.

In 1903, Frantz Jourdain founded the Salon d’Automne, whose exhibitions accompanied and amplified the ruptures then under way. Henri Matisse was a member of its governing committee, alongside other former students from Gustave Moreau’s studio at the École des beaux-arts. Charles Plumet was in charge of the overall scenography of the Salon.

When Julius Meier-Graefe published Histoire de l’évolution de l’art moderne (Modern Art: Being a Contribution to a New System of Aesthetics) in 1904, five years after opening his gallery, he titled the final chapter “Le nouveau rationalisme”, which he defined as a movement seeking to “renew the old through the abstraction of ornament”. He then listed the most significant figures in the decorative arts, including Plumet and the leading protagonists of L’Art dans Tout. Meier-Graefe also reproduced Matisse’s La Dame au chapeau vert [Woman with a Green Hat], a work barely completed at the time, shown at the Salon d’Automne of 1905 at the very centre of Plumet’s scenography – a Fauvist manifesto, a “pot of paint flung in the face of the public”.

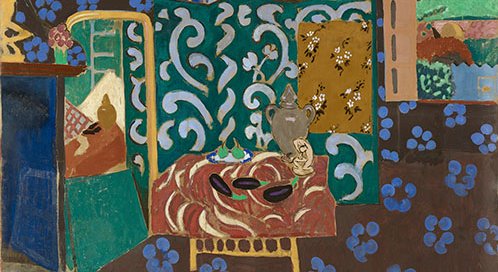

When Matisse painted Intérieur aux aubergines in 1911, the network of ornamental floral motifs and the matte colours of the tempera technique created the effect of wallpaper – a “décoration de muraille” the painter himself aspired to. He travelled to Morocco, Spain and Russia, and amassed a remarkable collection of textiles: fabric samples, tapestry fragments, toile de Jouy, Persian carpets, Arab embroideries, African hangings, cushions, curtains, shawls, costumes and folding screens. He referred to this collection as his “working library”.

When Matisse painted Intérieur aux aubergines in 1911, the network of ornamental floral motifs and the matte colours of the tempera technique created the effect of wallpaper – a “décoration de muraille” the painter himself aspired to.

Alongside paintings and sculptures, the Salon d’Automne also presented furniture, textile works and wallpapers by French designers. Charles Dufresne, André Groult, Jean-Louis Gampert, Louis Süe, André Mare, Paul Follot and Édouard Bénédictus all found in the national traditions of the 17th and 18th centuries qualities of clarity and order, drawing on their variations of fruit baskets and floral garlands. The path was thus opened to the naïve, brightly coloured floral imagery of the Atelier Martine, founded in 1911 by Paul Poiret. It was, in fact, in the couturier’s workshop that Matisse designed an emperor’s coat, a stage costume commissioned by Serge Diaghilev.

Floral motifs are everywhere, forms are simplified, colour takes precedence. Designers reveal what Léandre Vaillat described as “an attachment to pictorial values, asserted through the use of vivid and vehement colours… They are more concerned with impression than with form; they create what might be called an atmosphere for the interior” (L’art décoratif au SA, 1911).

The Salon d’Automne championed collaboration as a driving force behind the creation of modern interiors. In 1911, André Mare integrated works by Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Villon and Fernand Léger into his interior designs. A year later, La Maison cubiste invited visitors to step straight into a bourgeois living room, where Cubist paintings by Léger and Jean Metzinger were hung against Gampert’s floral wallpapers.

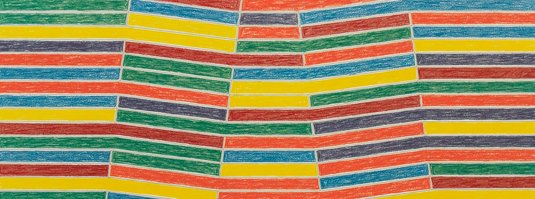

Walls of these rational interiors burst with intense colour – blazing orange, bright green, cobalt blue. In 1910, Frantz Jourdain invited members of the Munich Werkbund to present their work at the Salon d’Automne. No ornament. No décor. Just colour.

Modern art is meant to live alongside us. In an interior, a painting spreads colour like a quiet joy — a lightness that carries us.

Henri Matisse

The German displays sparked a wake-up call among French designers. More than anyone else at the time, Francis Jourdain pushed the idea of interior design to its bare essentials with his “meubles interchangeables” – a combinatory system of modular elements, economical furniture produced and distributed by the Ateliers modernes (1911).

In 1913, he published “Ornement et crime” in Les Cahiers d’aujourd’hui, the journal edited by George Besson – a French translation of Adolf Loos’s text envisioning a pure spiritual fulfilment of humanity. Le Corbusier would later reprint it in L’Esprit nouveau in 1921.

A few years before Matisse painted the portrait of their mutual friend, Francis Jourdain designed the interior of Georges Besson’s living room: a suite of vivid blue furniture that both clothed the wall and freed up space, for, as he put it, “the greatest luxury is to remove furniture.”

![Robert Mallet-Stevens, Hall pour Une ambassade française [Hall for a French Embassy], Pavillon de la Société des artistes décorateurs, Exposition de 1925 Published in René Chavance, « Une ambassade française » [A French Embassy], Paris, Charles Moreau, 1925, pl. 46 © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/2/csm_202010_Robert_Mallet-Stevens__Hall__publiee_dans_Une_ambassade_francaise__Paris_f7a2d81e9b.jpg)

Published in René Chavance, « Une ambassade française » [A French Embassy], Paris, Charles Moreau, 1925, pl. 46

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

![Noémie Skolnik-Hesse, Chambre d’enfant [Children’s Bedroom], n.d. Design for the private residence of Eric Allatini, built by Robert Mallet-Stevens, rue Mallet-Stevens, Paris, 1925–1927. Plate published in Répertoire du goût moderne, vol. 3, Albert Lévy, 1929, pl. 27 © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/1/csm_202010_Noemie_Skolnik-Hesse__Chambre_d_enfant_170747421e.jpg)

Design for the private residence of Eric Allatini, built by Robert Mallet-Stevens, rue Mallet-Stevens, Paris, 1925–1927. Plate published in Répertoire du goût moderne, vol. 3, Albert Lévy, 1929, pl. 27

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

Questioned by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1907, Matisse stated: “I have colours, a canvas, and I must express myself with purity – even if I have to do so summarily – by laying down, for example, four or five patches of colour, by drawing four or five lines with a plastic expression.”

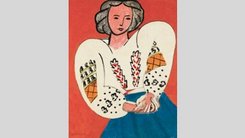

Throughout his career, the artist consistently praised the decorative dimension of his painting, profoundly altering the status of the image itself. To paint, he needed to remain as close as possible to his own emotion. The motif mattered less than the effect on the viewer, who, as Georges Duthuit would later write, must “let himself be taken without being aware of it” (Les Fauves, 1949).

I have colours, a canvas, and I must express myself with purity – even if I have to do so summarily – by laying down, for example, four or five patches of colour, by drawing four or five lines with a plastic expression.

Henri Matisse, questioned by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1907

In painting as in architecture, colour shapes a sensorial approach to space. In 1921, Le Corbusier published in L’Esprit nouveau the objective data of a physiology of sensations, as analysed by Eugène Chevreul and Charles Henry – whose work would go on to influence both architects and artists.

Stencil-coloured plate albums bear witness to the importance architects placed on colour: yellow ochre, red ochre, natural ochre, burnt ochre, raw sienna, burnt sienna, chrome yellow, English green, ultramarine blue, bleu charron, ivory black – hues that renewed the experience of interior space.

To Le Corbusier’s words, describing the role of polychromy in architecture – “Colour modifies space” – echo those of Matisse: “modern art is meant to live alongside us. In an interior, a painting spreads colour like a quiet joy – a lightness that carries us.” ◼

Cette présentation doit beaucoup aux travaux de Rémi Labrusse ainsi qu'à ceux menés lors de l'exposition « UAM, une aventure moderne », au Centre Pompidou en 2018.

Related articles

In the calendar

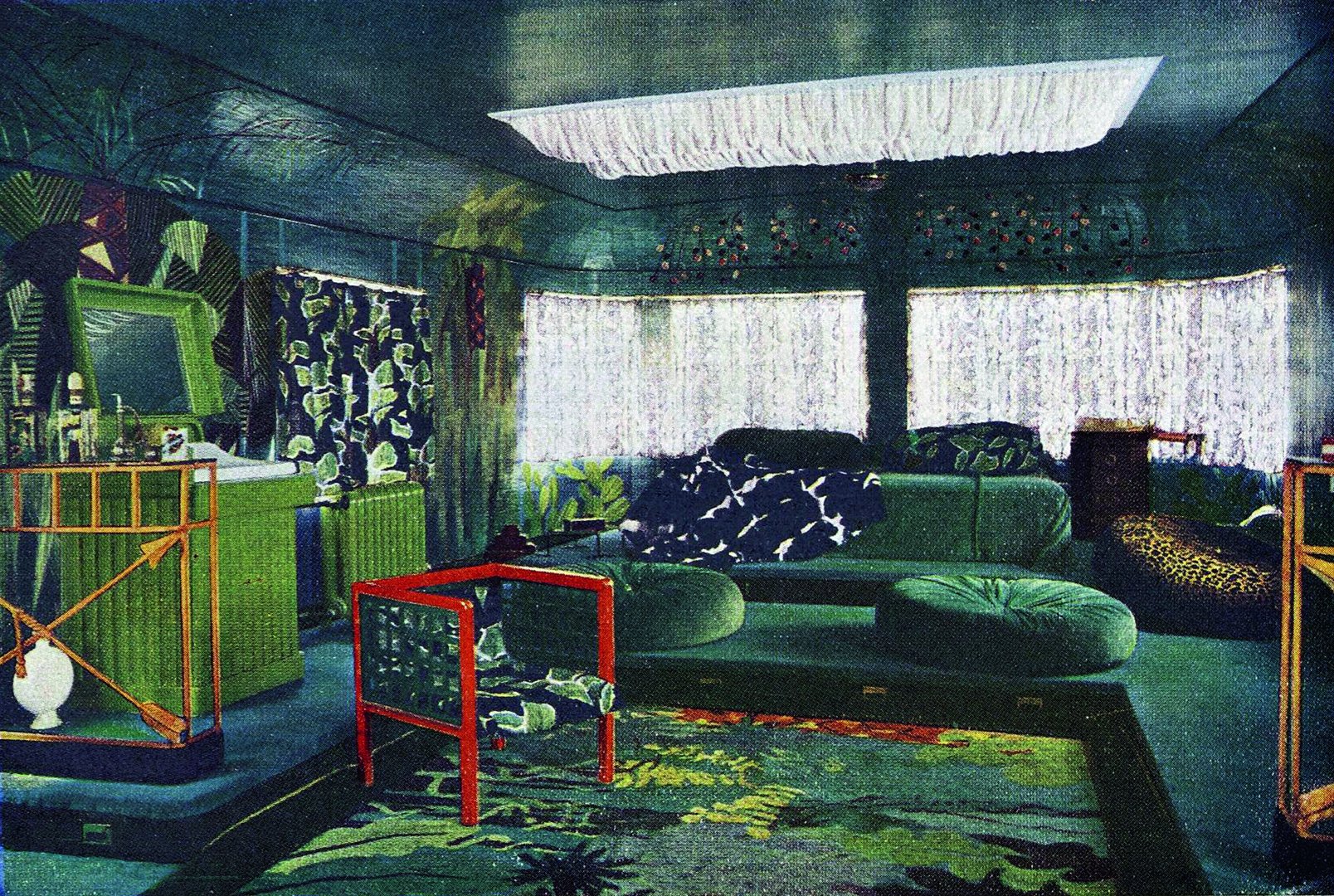

Paul Poiret, Atelier Martine, Aménagement intérieur d'une péniche sur la Seine, Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Grand Palais, Paris, 28 avril-8 novembre 1925

Photographie : L'Illustration (détail)

Commissariat de l'exposition « Matisse, comme un roman »

Aurélie Verdier

Conservatrice, Musée national d'art moderne

![Édouard Vuillard, Le Grand Teddy [The Large Teddy], 1918–1919 Oil on canvas, 150 × 290 cm Collection Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Geneva](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/9/csm_202010_Edouard_Vuillard___Le_Grand_Teddy_d07e5ac31d.jpg)