“Queer Zines”: The political journey of fanzines from gay and lesbian culture

How would you describe the role of print in your journey—as a person and as an artist?

AA Bronson – You know, I’m part of the hippie generation—the 1960s. I dropped out of university—like all the creative minds of that time—and, along with eight friends, we created a commune and an underground newspaper, The Loving Couch Press (1967–1968). We also had our own little shop, and so on. It was a typical experience of North American hippie communities at the time. Our goal with the paper was to create connections, to bring people together.

A few years later, in 1969, when General Idea came into being, a similar dynamic emerged: that of a pseudo-community. There were eight of us living together—until the group was distilled, in 1974, down to three members. At the time, there was a government programme called “Local Initiatives” that funded youth-led community projects. We were broke and asked ourselves what kind of community project we could propose. That’s when I recalled my experience with the underground press, and we came up with the idea to create FILE Magazine (1972–1989).

Canada is a country that stretches in a straight line from one ocean to the other. If you connect its main cities, you get a line that runs along the US border. No matter where you are, the nearest city is almost always in the United States, and when you turn on the television, most of the channels are American. As a result, Canadian artists were very scattered and communicated very little with one another.

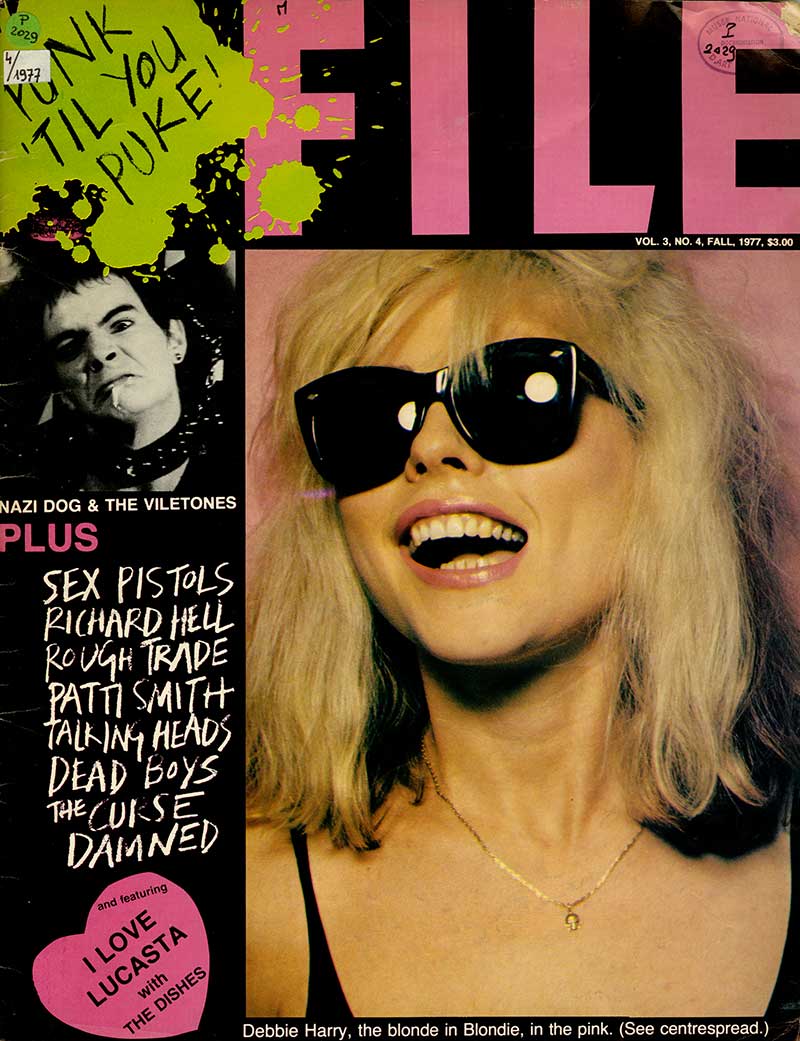

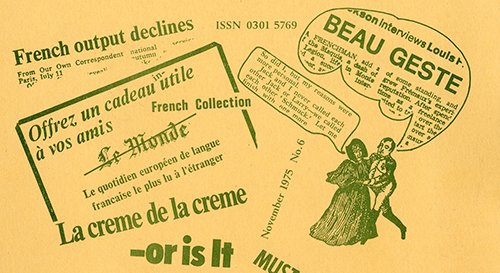

Our idea, then, was to create a small publication that would help build an artistic network. The first four or five issues were funded by the “Local Initiatives” programme—that’s how we launched the project. We chose a design and format inspired by the famous LIFE magazine, because we wanted it to be accessible, familiar, and instantly recognisable. We didn’t want an object that looked marginal or experimental at first glance. We wanted it to appear ‘normal’—at least on the outside. But once you opened it, it was anything but. What was surprising was that FILE attracted little attention in Canada. In contrast, it immediately found an audience in New York, London, San Francisco, Paris, Geneva, and Cologne. That’s how it all began.

With General Idea, you also created the Art Metropole space in Toronto, which became an important hub for distributing artists’ publications. How did that project come about?

AA Bronson – Two years after launching FILE, we realised there was genuine potential for international connection. But for that to happen, we needed organisation—a distribution structure. So we thought: “Since we’re already distributing FILE, why not distribute other artists’ publications too?” That’s how, in 1974, we founded Art Metropole, a centre dedicated to the distribution of artists’ books, magazines, videos, audio recordings, and any other non-traditional artistic format. Today, Art Metropole still exists, though it now operates primarily as a bookstore.

Were there any queer zines among the publications distributed by Art Metropole?

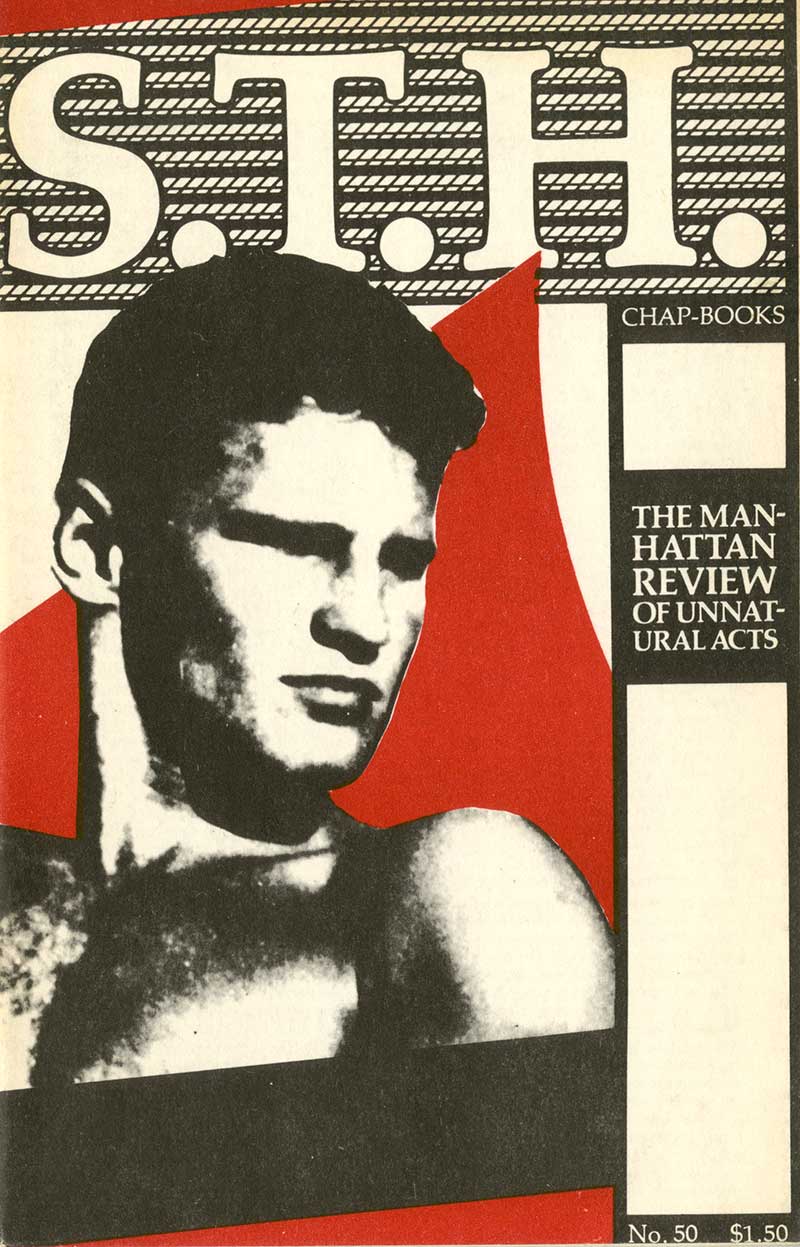

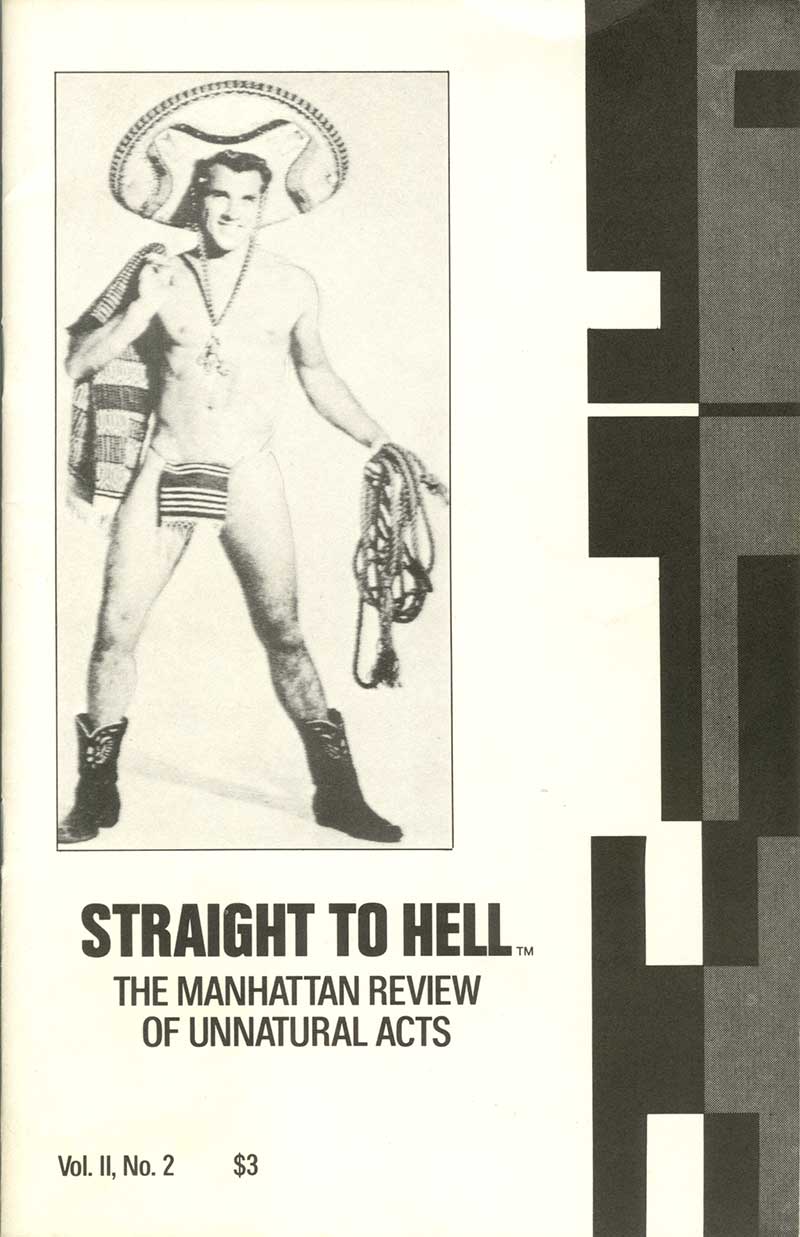

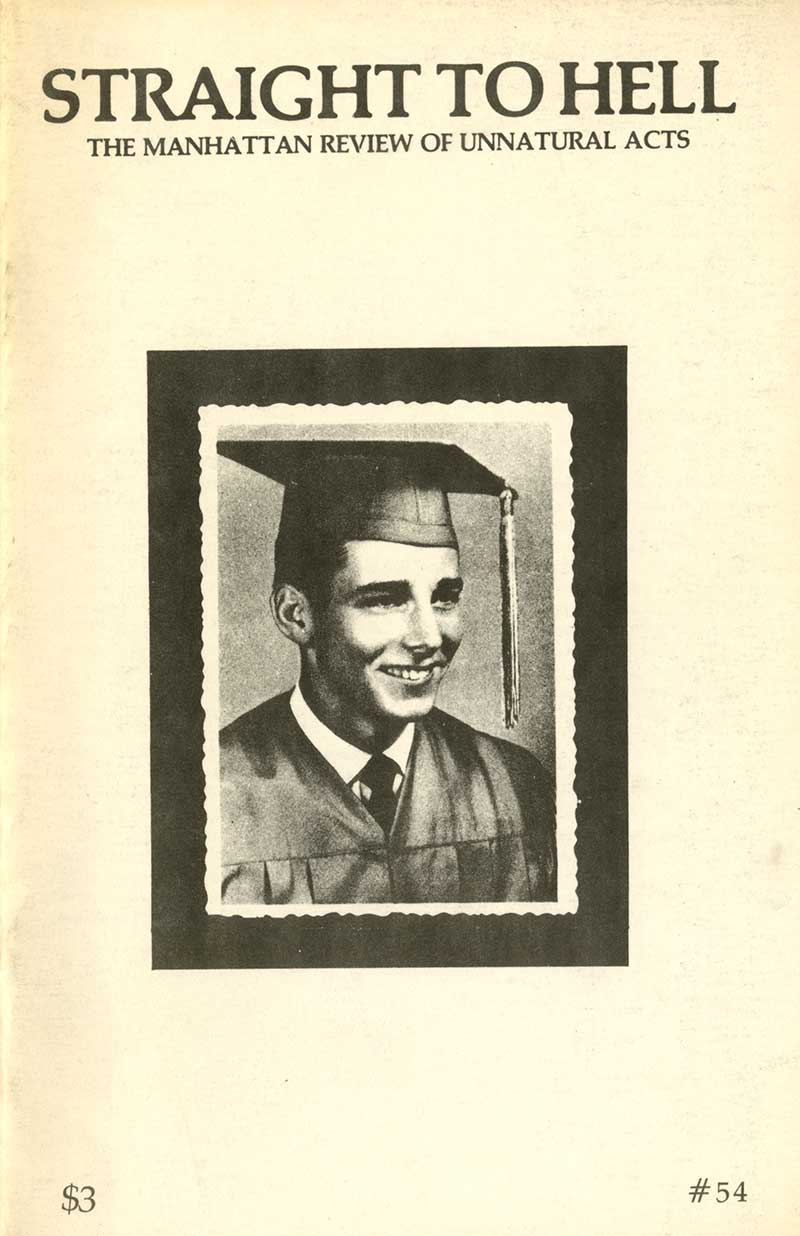

AA Bronson – Queer zines, as a movement, didn’t fully exist at the time. The first object I’d classify as a queer zine would be Straight to Hell (1971). When we opened Art Metropole in 1974, there were certainly some publications with a clearly queer identity, but that wasn’t our stated focus.

We distributed, for example, FILE, Fanzini, and several titles from Something Else Press, the publishing house founded in New York by author and artist Dick Higgins in 1963. We also carried the first publications by Gilbert & George, which were, in every sense, queer zines.

I remember that Straight to Hell was probably one of the first titles you told me you had bought.

AA Bronson – Yes, it’s a unique publication because it was entirely created by one man, Boyd McDonald. It operated much like mail art: his friends would send him stories about their sexual experiences—and the more unusual they were, the more he liked them! He published these accounts alongside personal ads that allowed readers to get in touch with one another, because at the time, being gay was still largely illegal. These publications were, therefore, a true means of connection.

Of course, it was first and foremost a little pornographic magazine, but it was crafted with such a conceptual approach that it also qualified as an artistic project. I later found out that Felix Partz, from General Idea, had contributed to it for years. He used to send in stories, though I never knew which ones were his.

We’ve always been fascinated by publishing around sexuality. When we went to Amsterdam in the 1970s to collaborate with the Stedelijk Museum, we were struck by the scale of the erotic bookstores there. They were like sex supermarkets, with an astounding variety of specialty magazines. Straight to Hell, however, stood out for the role it played in building a community, and that’s what led us to take an interest in queer zines.

But now that I think about it, I have to mention Fanzini (1972–1975) because on my very first trip to New York in the early 1970s, I met Ray Johnson and Jimmy De Sana for the first time. Ray, Jimmy, and I went on what Ray called an ‘art trip’. We left from downtown at one in the morning. At the time, venturing west of Seventh Avenue in the middle of the night was quite dangerous—it essentially meant avoiding more than half the city.

But we went anyway, crossing through the West Village and heading up to The Spike and The Eagle, the two big gay bars of that era, both located on the west side. We met many artists there and stayed for hours. That’s where we met the famous bartender John Dowd. He later became co-editor of Fanzini with John Jack Baylin, who was from the west coast of Canada.

By day, Dowd worked as a designer for posters, magazines, and other visual media. But on a personal level, he was already creating small queer posters and flyers for completely fictional, made-up projects. Baylin arrived in New York not long afterwards, and I believe Ray took him on the same kind of nighttime tour. That’s how he met Dowd, and together they had the idea: since we were doing FILE, why not create their own magazine? And that’s how Fanzini was born.

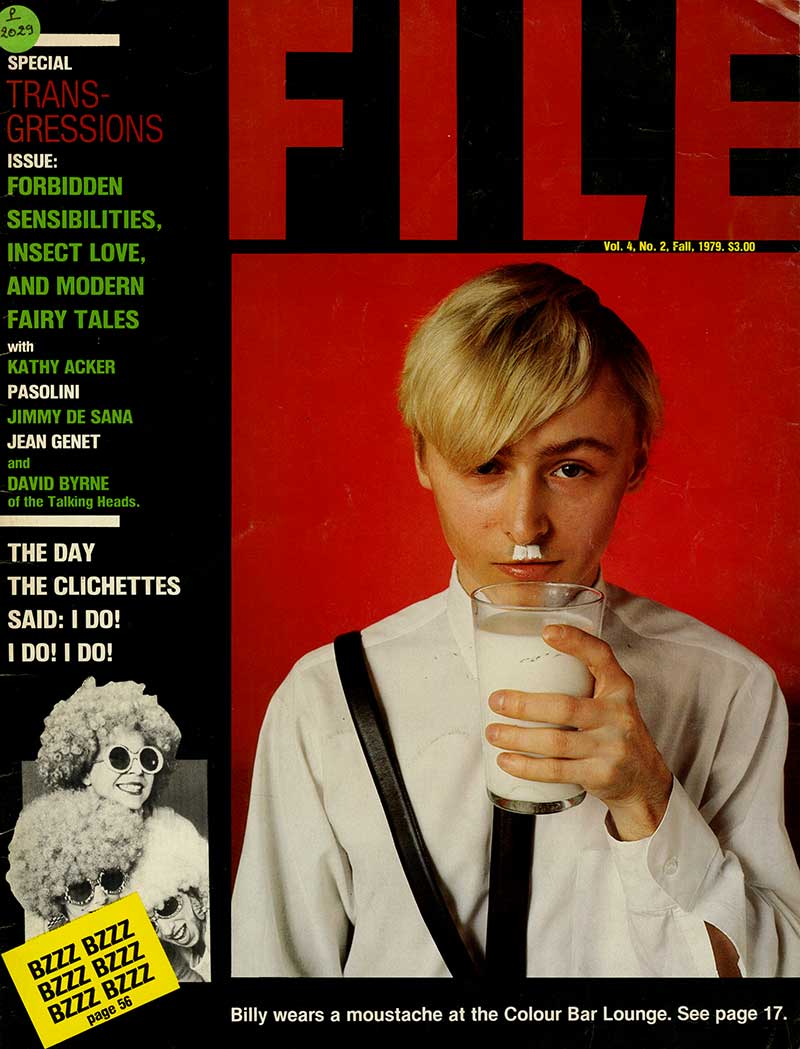

In a way, Fanzini aligns more directly with the queer zine tradition than FILE. But while flipping through FILE again, I came across the “Transgressions” issue from 1979, which actually includes quite a bit of sexual content. And then there’s also the “X-ray Sex” issue from 1982, which even features a reprint from Straight to Hell, amongst other things. Clearly, these themes were already on our minds at the time … Sex has been one of our concerns from the very beginning!

The successive editors of Straight to Hell—John Jack Baylin, and even yourself—were all connected to mail art at the time. I’m thinking in particular of the Image Bank collective, founded in Vancouver in 1970 …

AA Bronson – In the early issues of FILE, we published the Image Bank ‘Directory’, which listed people, addresses, and contacts connected to mail art. It was a group of mail artists based in Vancouver. We designed those listings in the style of the personal ads I mentioned earlier—except in this case, they were for mail art.

And it’s worth noting: a huge part of mail art was queer. Truly, an extremely high percentage! Very quickly, a network emerged, with figures such as Les Petites Bonbons in San Francisco, Ray Johnson and Jimmy De Sana in New York, Gilbert & George, and also Genesis P-Orridge in London, not to mention many others in Amsterdam, Paris, Florence … and, of course, General Idea in Toronto.

What was surprising about mail art was that a large part of it came from South America and Eastern Europe. Because, of course, any form of individual expression—and especially homosexuality—was illegal in those highly authoritarian countries at the time.

Locally, they weren’t allowed to do what they wanted, and their only means of communicating with the outside world was through these small publications, which then circulated by mail or through alternative art bookstores like Art Metropole in Toronto or Other Books and So in Amsterdam, run by another important queer figure, Ulises Carrión. And later on, of course, there was Printed Matter in New York—but that didn’t come along until the 2000s.

How did your collection of queer zines come about in this context?

AA Bronson – For nearly thirty years, I didn’t even think of it as a collection. It wasn’t until 1998, when I returned to New York, that I started to become aware of it. I had already lived in New York during the 1970s and 1980s, but after the passing of Jorge Zontal and Felix Partz in 1994, I moved back permanently in 1998.

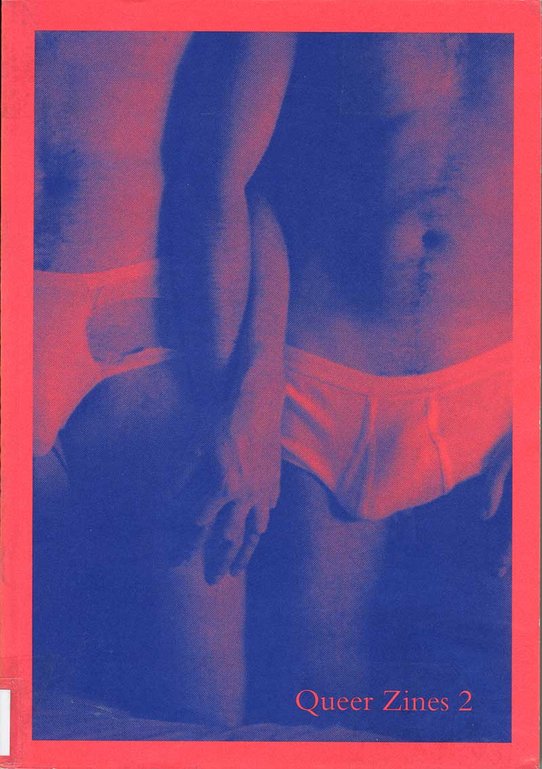

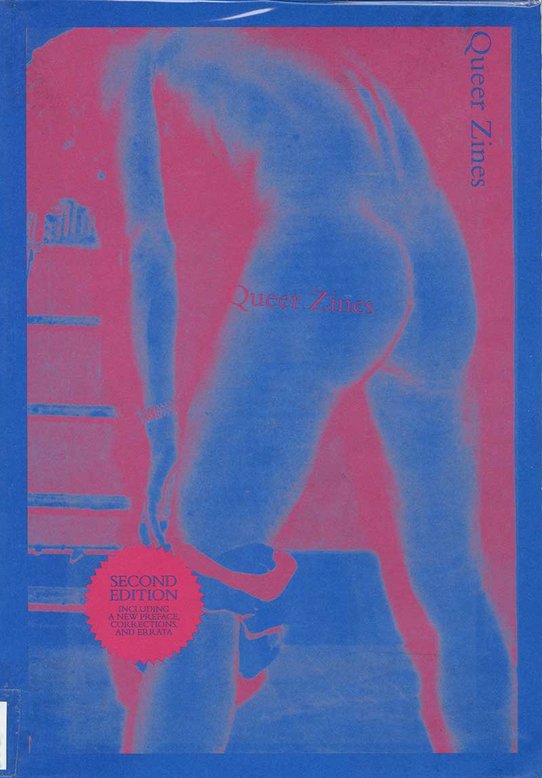

Then, in 2004, I became director of Printed Matter. That’s when I realised just how overwhelmingly heterosexual the material being offered was. There were very few queer publications available. So we decided to change that. At the NY Art Book Fair, we created a dedicated queer section, and Phil Aarons came up with the idea to organise the “QUEER ZINES” exhibition (2008), accompanied by an anthology. The project was built largely through the combination of his collection and Printed Matter’s holdings, with the addition of my more European perspective. At that time, there was a real revival in queer publishing, and we simply followed the momentum of that movement.

Looking through your collection, I noticed that many artists sent you their zines to be distributed via Art Metropole or Printed Matter. Your role seems to have been central in that regard…

AA Bronson – Yes, I ran Art Metropole in its early years, and then I was director of Printed Matter from 2004 to 2010. So I was in a position to launch the distribution of queer zines and give them genuine visibility. It was a personal passion.

Once we gained a reputation in that field, artists began sending us their publications—first to Art Metropole, then to Printed Matter. It felt like an entire segment of publishing was being completely overlooked, even by Printed Matter. We had to do something about it.

You also mentioned that many zines were given to you on a more personal level.

AA Bronson – Yes, I was given a lot of them in the 1970s and 1980s, especially the early ones. That came partly through the mail art network, but mostly through friendships. Zines are, above all, about networks.

I’m a true bookaholic—my life is surrounded by books. Eventually, I donated my collection of artists’ books to the National Gallery of Canada simply because it had grown too large and I could no longer manage it—not the queer zines, but my entire collection of art books, which must have totalled around twelve thousand volumes.

I’m never happier than when I’m surrounded by books. I don’t really draw distinctions like “this is my queer zine collection, this is my collection of something else”. I just love books—plain and simple.

You mentioned your collaboration with Phil Aarons on the “QUEER ZINES” exhibition and anthology. Did you plan the exhibition first, then the book?

AA Bronson – No, we conceived the exhibition and the book at the same time. It was Phil’s idea, and he very generously funded the publication. The whole project brought together his collection and mine.

What was the difference between your respective queer zine collections?

AA Bronson – I had a lot of publications from the 1970s and 1980s, mostly from Europe and South America, whereas his collection was, at first, much more focused on the United States.

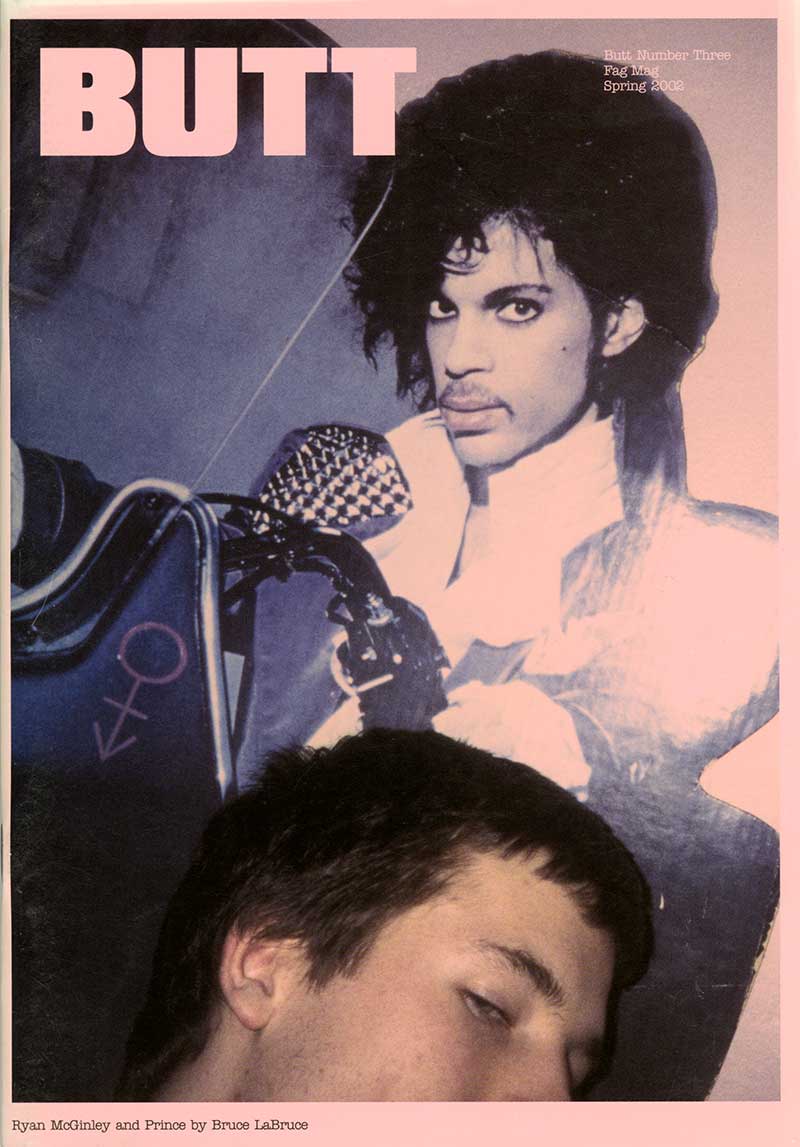

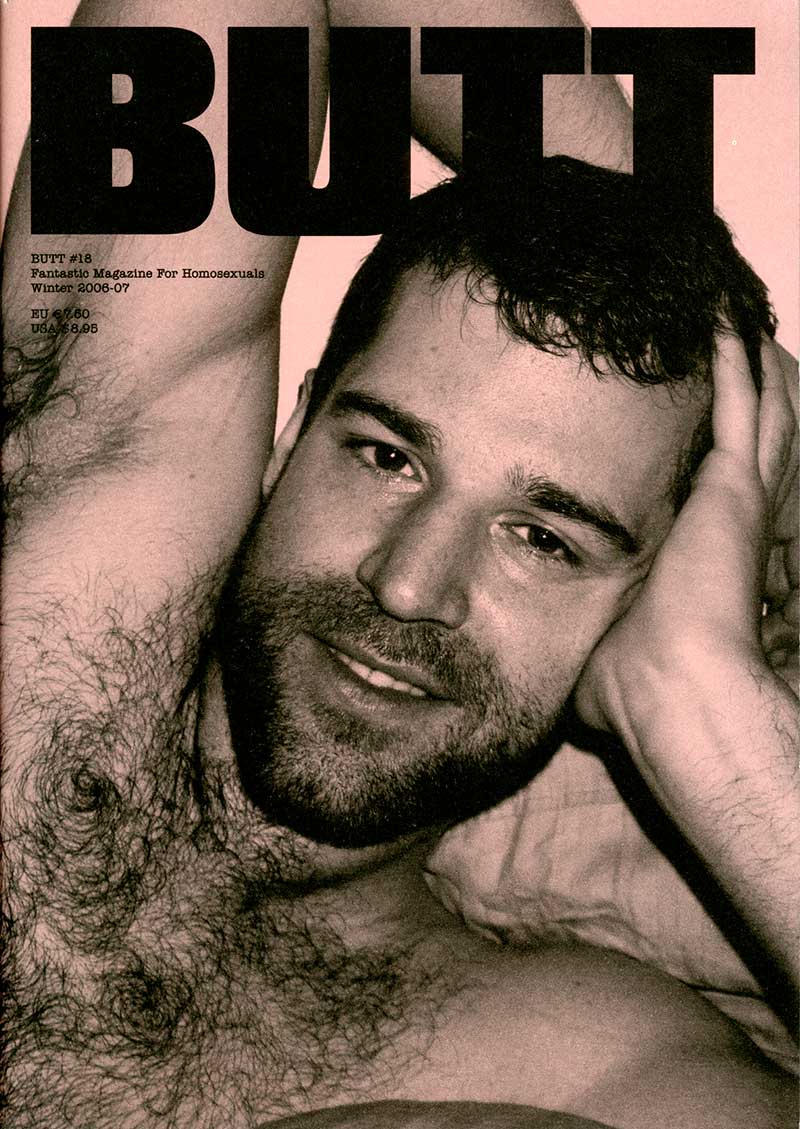

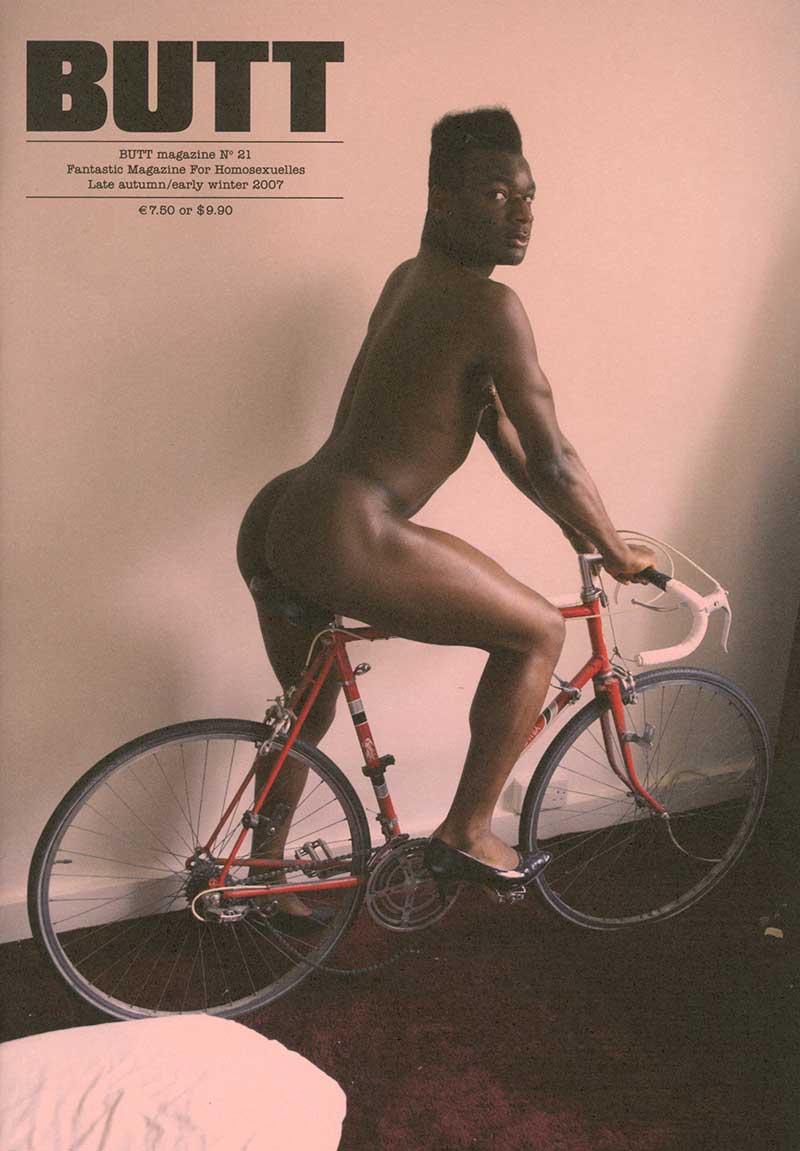

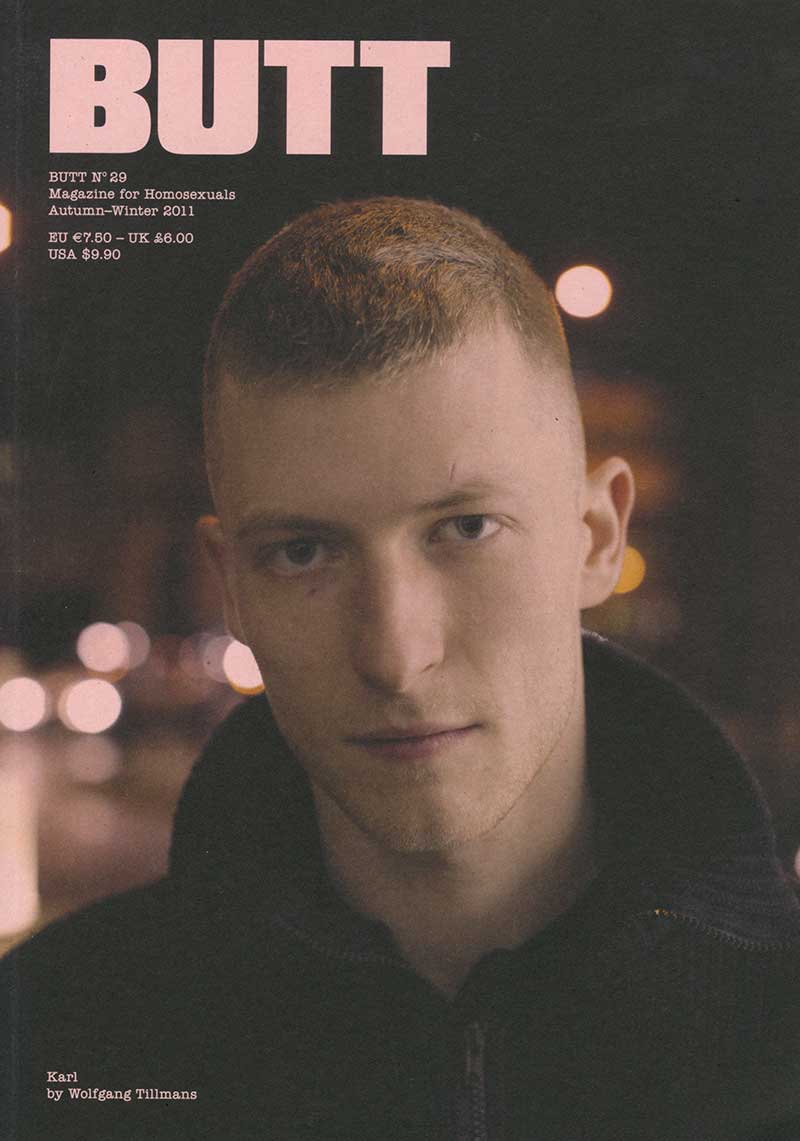

In the 2000s, there was a sort of queer zine revival. For example, BUTT (2001–) appeared, and a whole wave of new publications emerged. You could feel that a movement was beginning to take shape, that something was in the air, and that it needed more visibility.

That’s when we really started working on queer zines at Printed Matter. I think it was also around that time that Phil Aarons began building his collection—quickly, and with remarkable thoroughness.

What was the idea behind this two-volume anthology?

AA Bronson – Originally, there was only one volume. We had to work very quickly because we wanted the exhibition ready in time for the NY Art Book Fair in 2008. We had just three months to put everything together—the show and the book—it was completely crazy, but we pulled it off.

Later, we realised we had rushed so much that we’d left out a lot. So, on the occasion of the exhibition The Temptation of AA Bronson at the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam (2013–2014), we released an expanded edition of the first volume and added a second one, mostly to include all the new zines that had emerged in the meantime.

And why include zines in one of your own exhibitions, then?

AA Bronson – When I started curating my own exhibitions—after a lifetime of working collaboratively within General Idea—that was the only way I knew how to work: collaboratively. The exhibition in Rotterdam was built around the idea of queerness and collaboration. Each space in the gallery highlighted one of my collaborations or a project connected to other artists, most of whom were friends.

For the occasion, Printed Matter produced an updated version of Queer Zines, both as an exhibition and a publication. I also incorporated new elements tied to the zines: personal notes, objects I had received along with certain publications … and even a few sex toys. I always saw the Queer Zines room in that exhibition as a collaboration with Phil Aarons.

In a previous conversation between us, you offered an interesting distinction between a zine and a magazine…

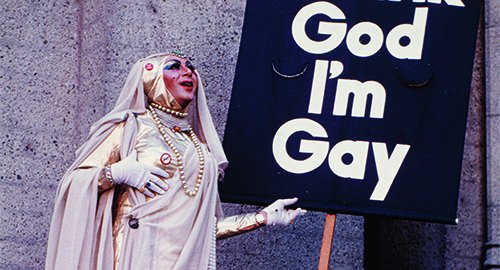

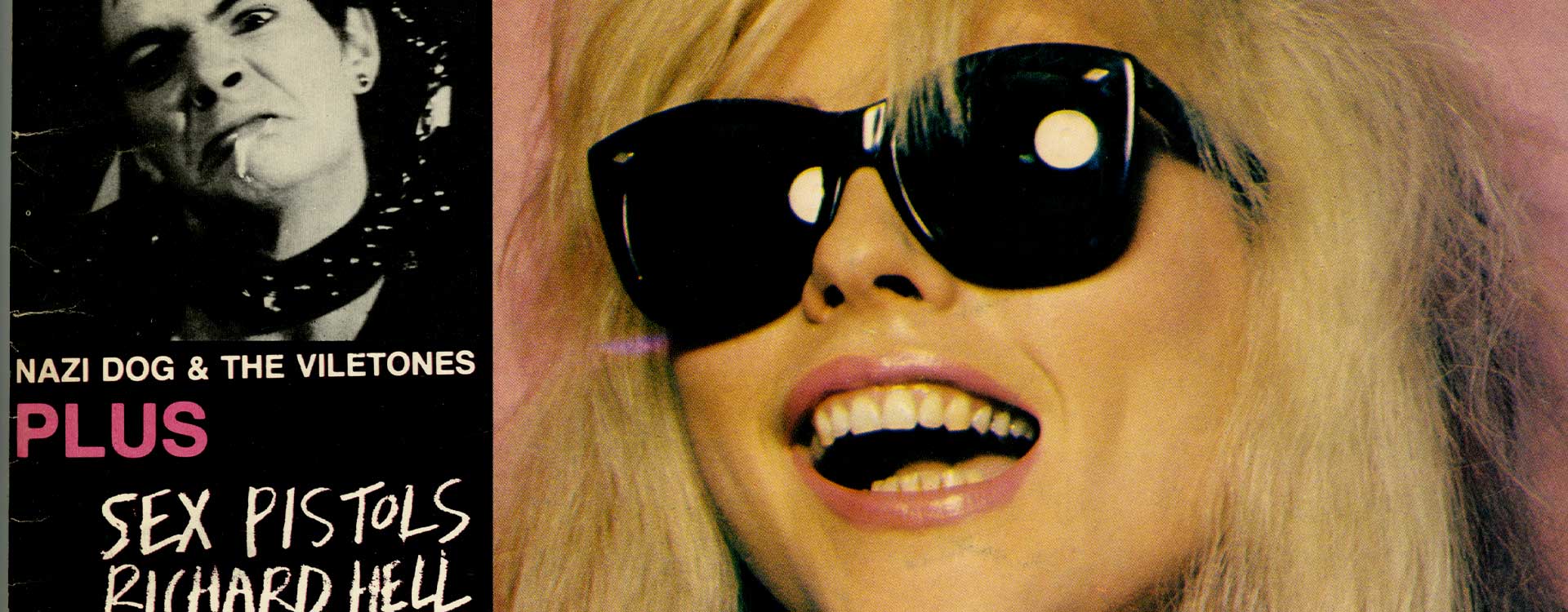

AA Bronson – To me, a magazine is a commercial product: it has advertising, professional distribution, and people who are paid to produce it. Zines, on the other hand, really emerged with the punk scene in the late 1970s. At that time, hundreds of punk fanzines appeared in London, and it’s fascinating to see them all together.

I had a collection of punk fanzines myself. They weren’t necessarily queer, but they were profoundly alternative—that is, created by and for the very people featured in them. That’s also what defines a zine: it’s not designed to be mass-marketed, but to be shared amongst friends.

There are also publications that sit somewhere on the boundary between the two. BUTT, for example. At first, it was just a group of guys in Amsterdam making a fanzine for themselves and their circle. But very quickly, they realised there was commercial potential, and today, it has become a real magazine—in the classic sense of the word.

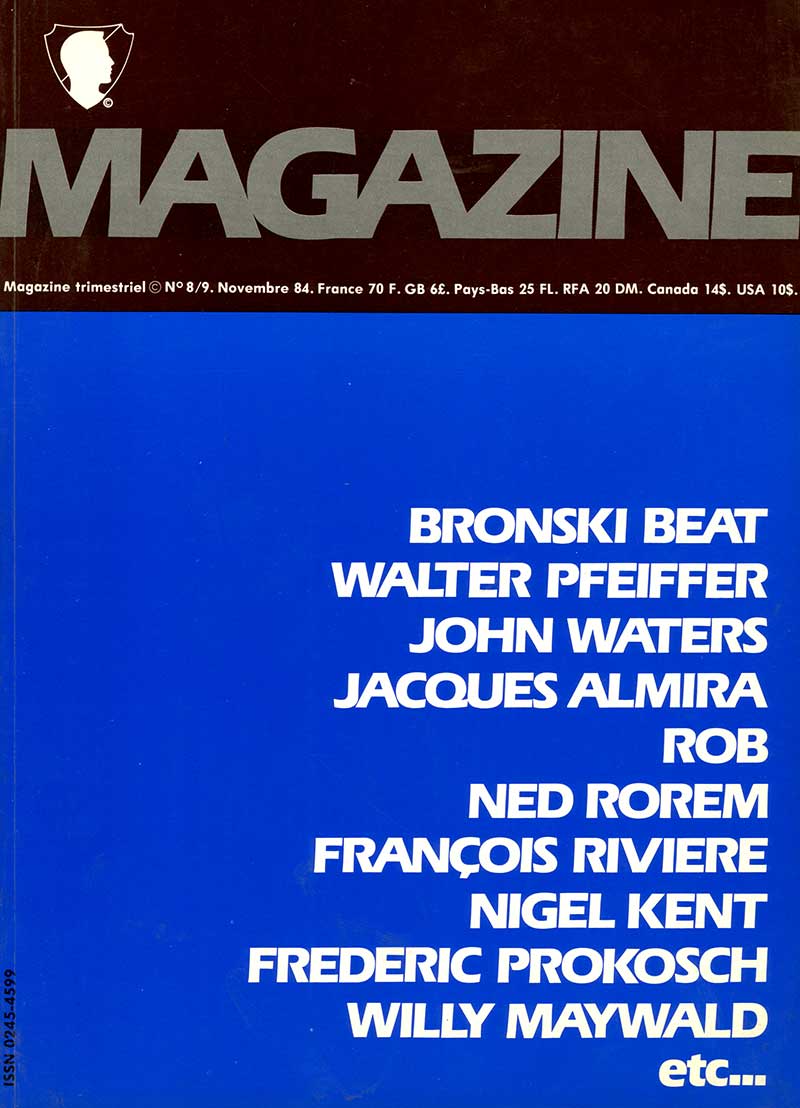

Another interesting example might be Magazine, edited by Didier Lestrade (1980–1986). Its format was that of a magazine, but to us, it was a zine—because of how it was produced, how it was distributed, and the audience it spoke to.

You also once described queer zines to me as a kind of ‘sensation’.

AA Bronson – Yes, they give off something—a feeling, a very distinct atmosphere. Just holding a good queer zine in your hands can provoke a physical reaction.

Because they’re transgressive?

AA Bronson – Yes, but also very intimate. There’s a certain tenderness in these publications. You could say they are tender and transgressive at the same time. In English, we like to say they’re … dirty! ◼

Le groupe Mission recherche des Amis du Centre Pompidou

Established in 2019 in close collaboration with the Bibliothèque Kandinsky, the "Mission recherche des Amis du Centre Pompidou" aims to contribute to the enrichment of the national collections through research and the dissemination of knowledge.

Each year, up to three research fellowships are awarded, enabling young scholars to carry out a research mission—under the supervision of a curator from the Centre Pompidou—through fieldwork, archival study, interviews, or previously unpublished translations.

Related articles

General Idea, File Magazine, vol. 3, no. 4, Fall 1977

© Centre Pompidou / Bibliothèque Kandinsky