Shuck One, graffiti artist and visual creator: “If you don’t know your own history, how can you speak to others?”

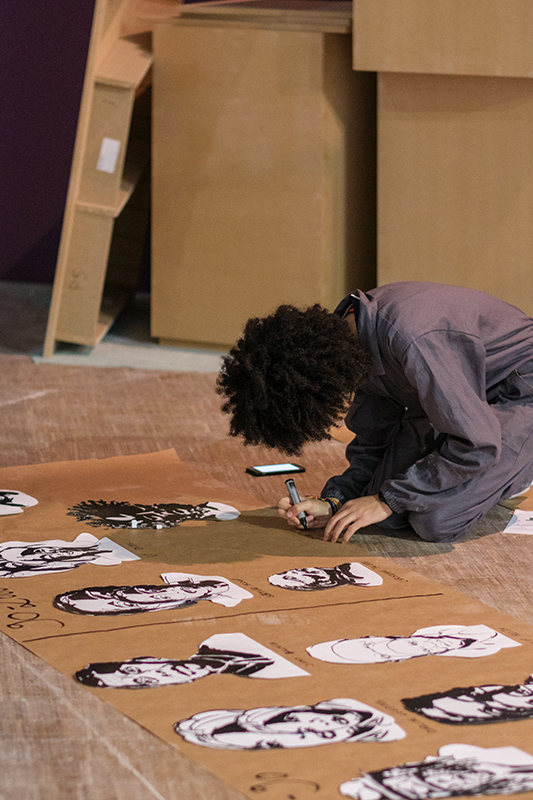

“Careful, don’t step on Aimé Césaire!” warns Guadeloupean artist Shuck One, in a gentle yet firm tone. He’s jovial but direct—his paint-splattered shoes reflect the vibrancy of the scene: several art students assist him attentively, following his precise instructions. Against the wall, dozens of neatly stacked paint cans resemble a giant colour chart. Nearby, a large stepladder and mobile scaffolding hint at the scale of the project. At the centre of this orchestrated chaos, a rectangular table serves as a hub—every item arranged with meticulous care, contrasting with the surrounding creative frenzy. Scattered on the floor, dozens of black-and-white sketches depict key historical figures, ranging from the independence movements to pan-African and anti-racist struggles.

“It’s a powerful project”, says the artist, who traces memory from the period 1914 to 1990, bringing together forty-one Afro-Caribbean figures—some forgotten, most overlooked. Artists, writers, thinkers, activists—all Black, all having contributed to the making of Paris. “I wanted to highlight some figures I already knew, and others I discovered through my reading of the history of France—Afro-Caribbeans who gave their lives for Paris: for cultural Paris, literary Paris, artistic Paris, for the city itself.”

I wanted to highlight some figures I already knew, and others I discovered through my reading of the history of France—Afro-Caribbeans who gave their lives for Paris: for cultural Paris, literary Paris, artistic Paris, for the city itself.

Shuck One

Paulette Nardal, James Baldwin, Gontran Damas, Sarah Maldoror, Angela Davis … Each portrait finds its place within the vast mural Re-Generation 2025, ten metres by four, specially commissioned by the Centre Pompidou for the "Paris noir" exhibition. With an encyclopaedic ambition, the work weaves together political moments to trace African and Caribbean migrations. It reveals the complexity of human relationships through traces, wounds, ruptures, and syncopations left by history—just as much as it reflects the artist’s own expressive path.

Born in Pointe-à-Pitre in 1970, Shuck One first encountered wall inscriptions in 1979 while out walking with his grandmother Solitude—texts in Creole scrawled across public buildings, letters meant to capture attention, calling for freedom from the evils of colonisation. “At the time, it wasn’t yet graffiti as we know it”, he explains, “but political slogans: calls from independence movements, anarchists, appeals for the island’s liberation from France. These words, hastily painted or scribbled, already carried power—a cry, a history. I was nine.” That was all it took; by eleven, he was a young activist, supported by his uncle, while his grandparents, concerned, tried to shield him. “It was an awakening”, he says. “I was becoming aware of who I was, where I came from, and what I wanted.”

Shuck One first encountered wall inscriptions in 1979 while out walking with his grandmother Solitude—texts in Creole scrawled across public buildings, letters meant to capture attention, calling for freedom from the evils of colonisation.

As a teenager, he wanted to rename streets, take part in protests. It was at the Rémi Nainsouta (1883–1969) Library—named after a leading figure in Guadeloupe’s social, economic, and cultural advancement—that he taught himself about politics and literature by reading books placed on the highest shelves, out of reach. “Every Saturday, I’d spend the afternoon reading,” he recalls, adding with a smile, “One librarian would sigh when she saw me: ‘Here comes trouble again.’” He even admits to having stolen a few books to quench his thirst for knowledge. Though he was already drawing and painting and was an informal attendee at the Centre for Graphic and Applied Arts in Pointe-à-Pitre, Shuck One saw himself more as an activist than an artist.

Yet everything changed when he moved to Paris at the age of fourteen to join his parents. “In the metro, I discovered tags and graffiti. It was a form of artistic expression, though not very political. I already knew a bit about it from the US, through Canal 10 (a Guadeloupean TV channel). I identified with it, chose the name Shuck, and started tagging.” On the walls of his school, in his neighbourhood, in the metro—especially lines 2, 9, and 13, between the stations Mairie de Clichy and Alexandre Dumas—and even in the catacombs. By the late 1980s, his crew DCM had become a landmark in French graffiti. “I quickly became one of the kings of the metro”, he says. “But I always insisted on my freedom: being part of a group, yes, but never bound by its codes.”

“I came from Guadeloupe with a strong political awareness. I’d tell them: ‘If you don’t know your own history, how can you speak to others?’”

Shuck One

The streets, wastelands, metro tunnels… “It’s the early ’90s and we want our story to endure.” Supporting himself as a crew member at McDonald’s, Shuck One turned to painting. From wall to canvas. He set up in a squat called Garage 53 and began selling politically charged works, which pushed him to refine his technique further. “I’d sell a canvas every week—1,000 francs each. Mostly to foreign collectors, and I barely spoke English.” He sees his work as distinct from what he calls “négropolitains”—young people unaware of their origins, language, or history. “I came from Guadeloupe with a strong political awareness. I’d tell them: ‘If you don’t know your own history, how can you speak to others?’”

His institutional breakthrough came in 1991, one year after founding the Basalt collective—Parisian graffiti artists who helped shape the scene and legitimise graffiti as an art form. That year, Shuck One took part in "Ten Years of Graffiti Art" at the Palais de Chaillot. This major event brought together leading French and American graffiti artists, celebrating a decade of urban expression. By showcasing graffiti in such an iconic venue, the exhibition played a decisive role in its recognition as a form of contemporary art. “Ten American artists, ten French artists”, he recalls. “I was among the youngest selected. What interested people was my message: using graffiti to talk about a political context.”

But wary of repetition or entrapment, Shuck One set off in 1995 to explore other parts of the world—Africa, South America—a vital journey of two to three years, like a return to his roots. That period marked the start of lectures, UNESCO scientific committees on the slave trade, and more. “It was vital. I needed to refill my tank, to grow, to break free. I didn’t want graffiti—which I loved—to become a cage. So I broke the letters apart and moved towards a freer abstraction.”

Graffiti was a doorway—I never wanted it to become a prison.

Shuck One

This free-flowing approach fully reveals itself in his mural Re-Generation 2025: “Today, I’m not creating a work—I’m transmitting memory. These are fragments, stories I project onto walls, in colour, in volume. Graffiti was a doorway—I never wanted it to become a prison.” As for the portrait of the artist’s mother, it’s up to viewers to find it within the works—unless, in the end, he decided to keep it just for himself …

Related articles

In the calendar

© Pierre Malherbet