The Secret History of the Maison de Verre, a Masterpiece of Modern Architecture

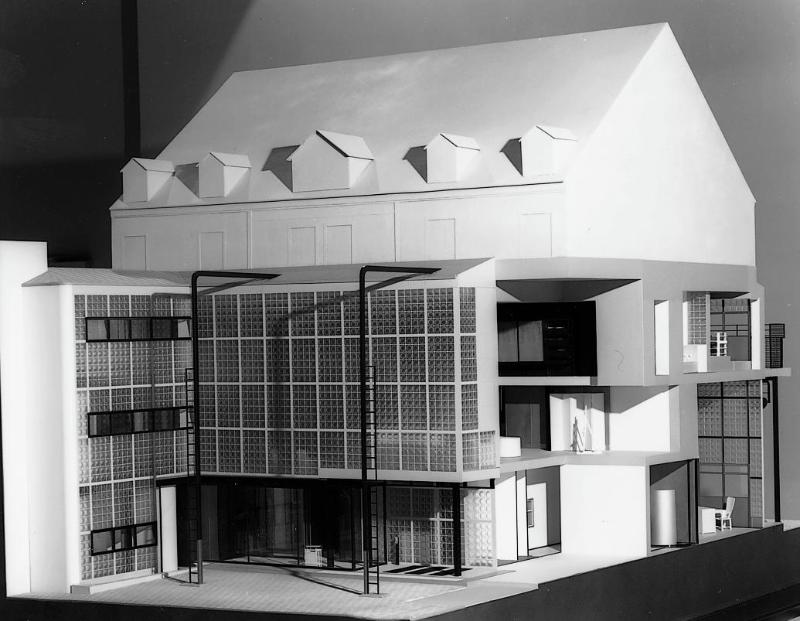

In 1925, when Annie and Jean Dalsace decided to build their home at 31, rue Saint-Guillaume—on the site of a dark, aging townhouse—they hadn’t anticipated that the elderly woman living on the top floor would stubbornly refuse to move out. They were forced to redesign the entire building without touching her apartment. A formidable challenge. To meet it, they made a bold and unconventional choice: rather than hire a traditional architect, they turned to a friend—Pierre Chareau.

At the time, Chareau was already an acclaimed furniture and interior designer, known for his refined craftsmanship, inventive compositions, and his ability to conceive living spaces as cohesive environments. The Dalsaces had seen his talent firsthand: just after the war, as newlyweds, they had asked him to furnish and decorate their apartment on boulevard Saint-Germain. For Jean Dalsace, Chareau created a custom-designed desk that would later be shown at the 1920 Salon d’Automne—marking a turning point in his growing reputation.

In 1925, when Annie and Jean Dalsace decided to build their home at 31, rue Saint-Guillaume—on the site of a dark, aging townhouse—they hadn’t anticipated that the elderly woman living on the top floor would stubbornly refuse to move out.

In the immediate postwar years, Chareau ran his practice from his home on rue Nollet in Paris’s 17th arrondissement. In 1922, he opened a small boutique on the Left Bank, rue du Cherche-Midi, managed by his wife Louisa Dyte, known as Dollie. There, he offered lighting—often recognisable by their metal frames inlaid with alabaster—and domestic furniture made of rare woods, finished in leather or in tapestries by his close friend Jean Lurçat. Today, the Kandinsky Library holds over five hundred photographs of these designs—furniture and objects—carefully archived in twelve volumes from Chareau’s professional catalogue.

By the time the young couple approached him with the idea of building a home, Chareau was already in the spotlight following the 1925 "Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes", where he had presented a library-desk designed for a modern embassy. Its striking form—resembling a piece of architecture—drew widespread attention. That this design dates to the same period as the conception of the Maison de Verre is no coincidence. It reflects Chareau’s deeply integrated approach to domestic space.

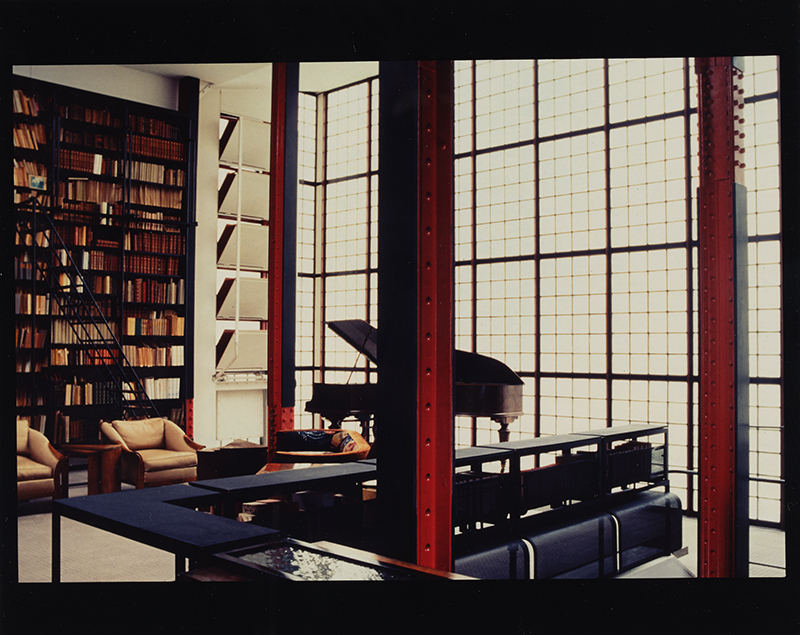

For the Maison de Verre, he would go on to design three distinct zones: a professional space for Jean Dalsace, a gynaecologist and early advocate of family planning; a private family living area; and a reception space—something the Dalsaces considered essential to the life of the home.

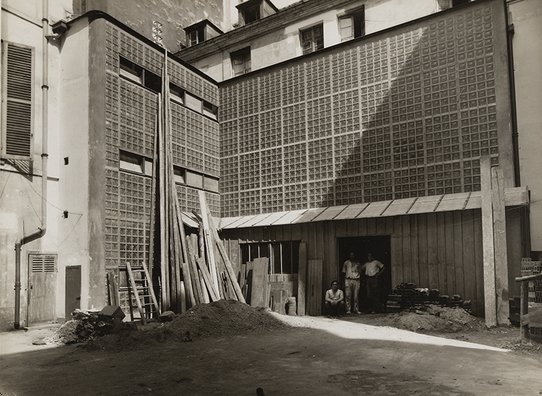

Construction of the Maison de Verre would take several years. Pierre Chareau enlisted renowned artisans, many of whom were members of the Union des artistes modernes (UAM). To create this house—a true metal skeleton wrapped in a skin of glass—Chareau chose light as his primary material. Master metalworker Louis Dalbet erected the steel framework, which Chareau boldly left exposed, transforming it into a key decorative element. Dalbet also forged and assembled the metal staircases, the curves of the railings, and the grating-style metal steps. He crafted the perforated sheet-metal partitions—some movable or rotating—as well as unusual features such as the built-in serving hatch. Alongside lighting designer André Salomon, a pioneer of indirect illumination, Dalbet helped create the house’s signature light fixtures. Working together on-site, Salomon and Chareau developed the concept of an 'architecture of light'.

To create this house—a true metal skeleton wrapped in a skin of glass—Pierre Chareau chose light as his building material.

Until its completion in 1932, Annie Dalsace visited the construction site daily, supporting her friend Pierre Chareau, who was wearing himself out in pursuit of perfection. “Tell me I fought like a lion for our house,” he wrote to Jean Dalsace in a letter dated 13 June 1932. As the glass bricks were finally inserted into the steel framework, the tension reached its peak. Would this technical feat live up to the aesthetic ambition and the sheer tenacity behind it?

History proved Chareau and his collaborators right. The photographic archives and correspondence preserved in the Dalsace collection document how this house—born of technical challenge and creative invention—became, once completed, a vibrant place of life for its owners: a family home, yes, but above all, a cultural hub. Sculptors, painters, gallerists, musicians, writers, dancers, and other artists passed through its rooms. Numerous invitations bear witness to this, as does the richness of the vast library in the main salon. Many rare and important works from this collection were donated to the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 2019. The Bibliothèque Kandinsky holds a number of volumes—many bearing personal dedications—as well as periodicals, mostly from the interwar period. The correspondence includes letters from sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, Jean Lurçat, gallerist Jeanne Bucher, Madeleine and Darius Milhaud, and dancer Djémil Anick, for whom Chareau would later design a house in 1937.

During the war, the house was saved by the transparency of its walls, which made it unappealing for German occupation.

The war drove most of the protagonists out of Paris. The Dalsace family left for Clermont, then Marseille. Dollie Chareau joined her husband in New York. Jeanne Bucher was tasked with overseeing their Parisian properties, and she arranged for painter Nicolas de Staël to take up residence in Pierre Chareau’s former address on rue Nollet. The Maison de Verre itself was spared, in part because its transparent façade discouraged any plans by the occupying forces to requisition it.

After the war, the Maison de Verre came back to life, once again hosting artists and cultural events. Around René Herbst and a circle of close friends, efforts began to promote and preserve Chareau’s work. An exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs was being planned when Pierre Chareau passed away in 1950. A monograph followed, entirely funded by subscriptions—an initiative driven by Herbst, the Dalsace family, and Dollie Chareau, who, from the United States, rallied the architect’s admirers.

The Dalsaces worked actively to promote the Maison de Verre, both as a subject in its own right and as an exceptional setting for cultural and editorial events. In 1977, their daughter Aline Dalsace (later Vellay) founded the Friends of the Maison de Verre association. Acting as guardians of its memory and champions of its architectural significance, the family and a circle of devoted supporters worked to preserve and share the house as a symbol of modernity—breathing new life into it with each initiative.

In 2005, the house was purchased by American collector Robert Rubin. Since then, it has remained largely out of view to the general public.

These archives are not just about Pierre Chareau or the Dalsace family. They are not merely a record of the work of an architect-designer, or a chronicle of friendship between an artist, his collaborators, his patrons, and his admirers. These sixty-five boxes of documents represent all of that—and more. Above all, they are what the house itself has gathered and preserved under its roof: the memory of the Chareau family, that of the extended Dalsace family, Marc Vellay’s research materials, and the workings of an association. For the archivist, this multifaceted collection is structured around the Maison de Verre as a living entity.

The Maison de Verre is certainly the least known but the most beautiful house of the 20th century.

— Richard Rogers

Like the people who imagined it, built it, inhabited it, wrote about it or worked to restore it, the Maison de Verre has charted its own story across generations—loved and protected by those who dreamed it into being, and by their grandchildren, who in June 2022 entrusted this remarkable archive to the Bibliothèque Kandinsky.

Encompassing the exhibitions and publications it has inspired (articles, books, films, lectures…), as well as the honours it has received (it was designated a historic monument in 1983), the Maison de Verre now continues to write its intergenerational history through this new research resource. A modern home that has inspired countless architects—including Richard Rogers, who wrote in 1966 that it was “certainly the least known but the most beautiful house of the 20th century.” A house all the more venerable now that it has passed the threshold of its first hundred years. ◼

Related articles

Façade of the Maison de Verre, 1979

Photo © Elisabeth Novick

© Centre Pompidou / Bibliothèque Kandinsky