Silkworms, a Stolen Painting, and the Shadows of War

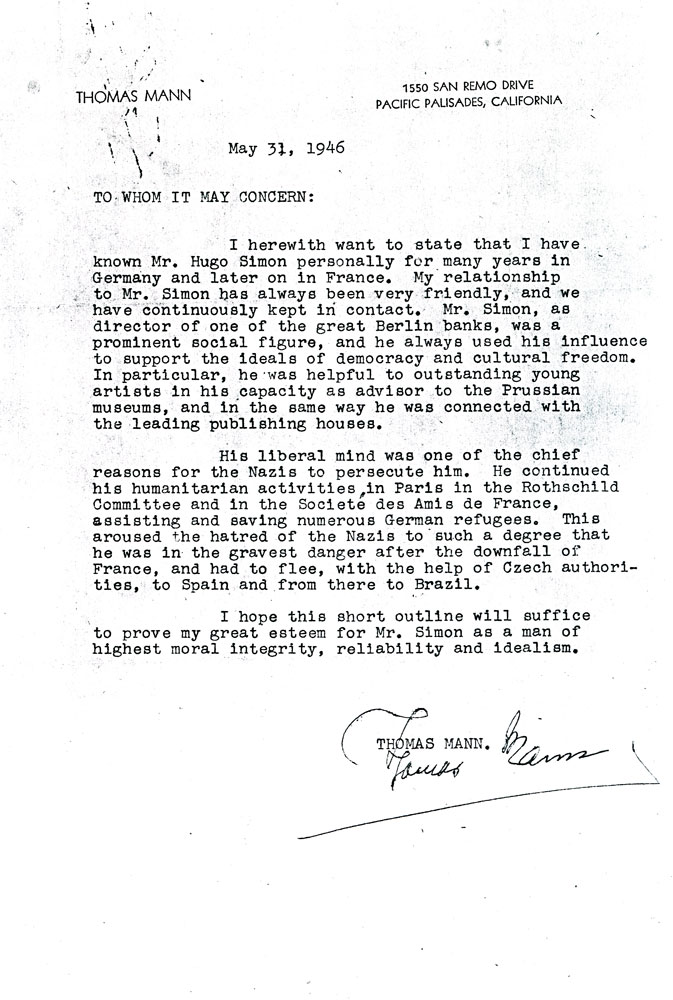

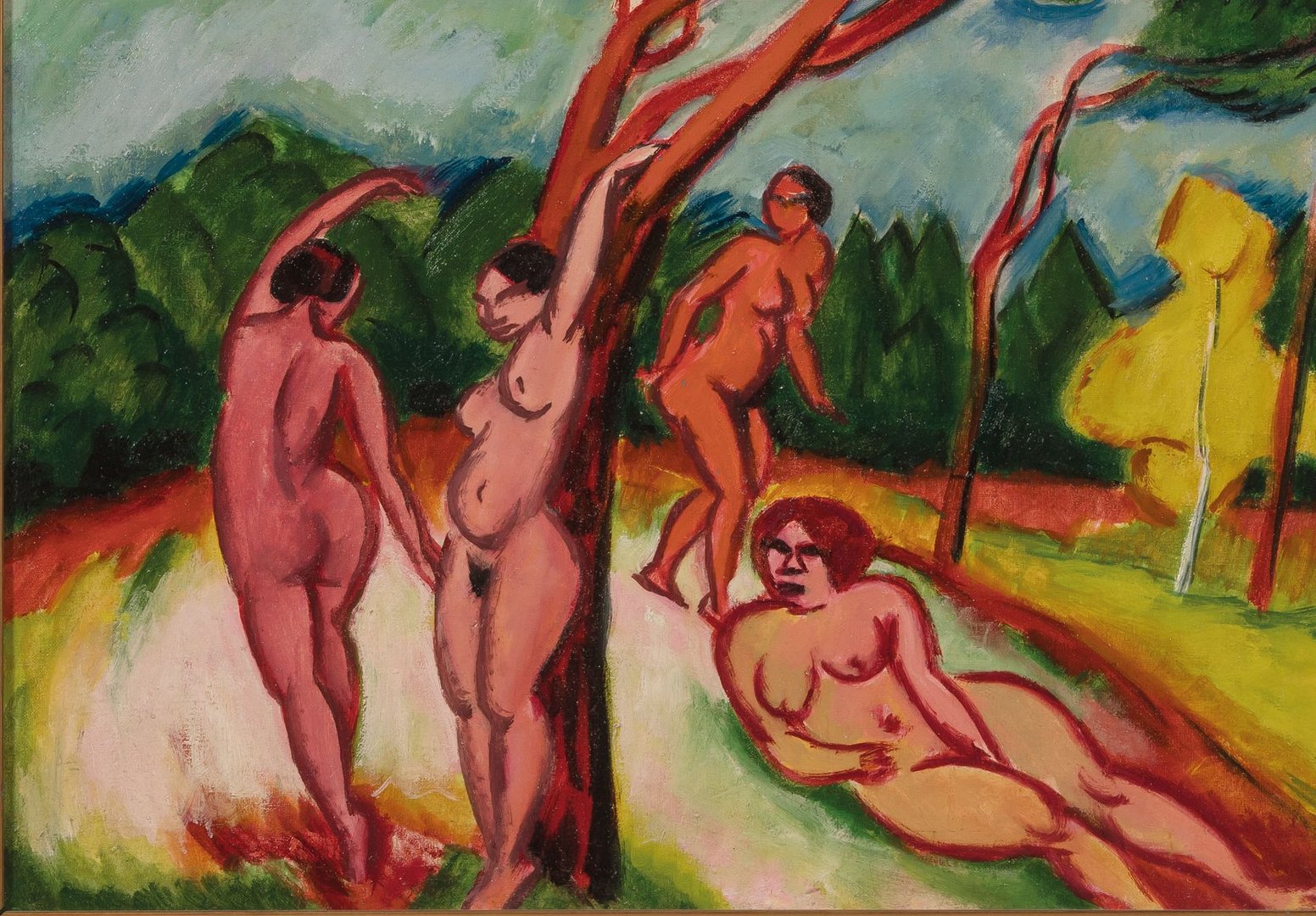

It is a vivid, colorful painting: naked women in a landscape that might appear serene — were it not for its stormy sky. Its title? Vier Akte in Landschaft (Four Nudes in Landscape) — known in French as Nus dans un paysage or simply Paysage. Painted in 1912, the work is by Hermann Max Pechstein, a key figure of German Expressionism, closely associated with Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and one of the artists denounced by the Nazi regime as producers of so-called “degenerate art.”

In 1966, the painting entered the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne under inventory number AM 4364 P. Yet for decades, its origins remained unknown.

Following years of research — notably by Angela Lampe, curator of the modern collections, and Didier Schulmann, chief heritage curator — it was determined that the painting had been the subject of Nazi-era looting from Jewish owners.

On July 1st, Vier Akte in Landschaft was finally returned to the rightful heirs. It marked the conclusion of a long-running case — one that reveals not only France’s troubled past, but also its commitment to reparation.

On July 1st, during an official ceremony at the Ministère de la Culture in the presence of Minister Roselyne Bachelot, Vier Akte in Landschaft was finally returned to the rightful heirs. It marked the conclusion of a long-running case — one that reveals not only France’s troubled past, but also its commitment to reparation.

Roselyne Bachelot stated: “Restitution is an act of reparation; it reestablishes a link between generations, between those who were looted and their descendants. May it also help to dispel, even slightly, the shadows cast by exile and persecution.”

In September 1966, when this 71 x 80 cm oil on canvas appeared in the storage rooms of the Palais de Tokyo — then home to the Musée National d’Art Moderne — nothing was known about its provenance. And yet, the painting had been added to the French national collections inventory, without the standard acquisition procedures. So where had it come from?

A nearly illegible label on the back of the canvas gave researchers their first lead in 2005. The painting had been loaned to an exhibition in London in 1938. Entitled "Twentieth Century German Art", the show was organised by art critic Paul Westheim, who had fled to Britain. It focused on anti-Nazi artists — a direct counterpoint to the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition held in Munich in 1937.

In September 1966, when this 71 x 80 cm oil on canvas appeared in the storage rooms of the Palais de Tokyo — then home to the Musée National d’Art Moderne — nothing was known about its provenance. So where had it come from?

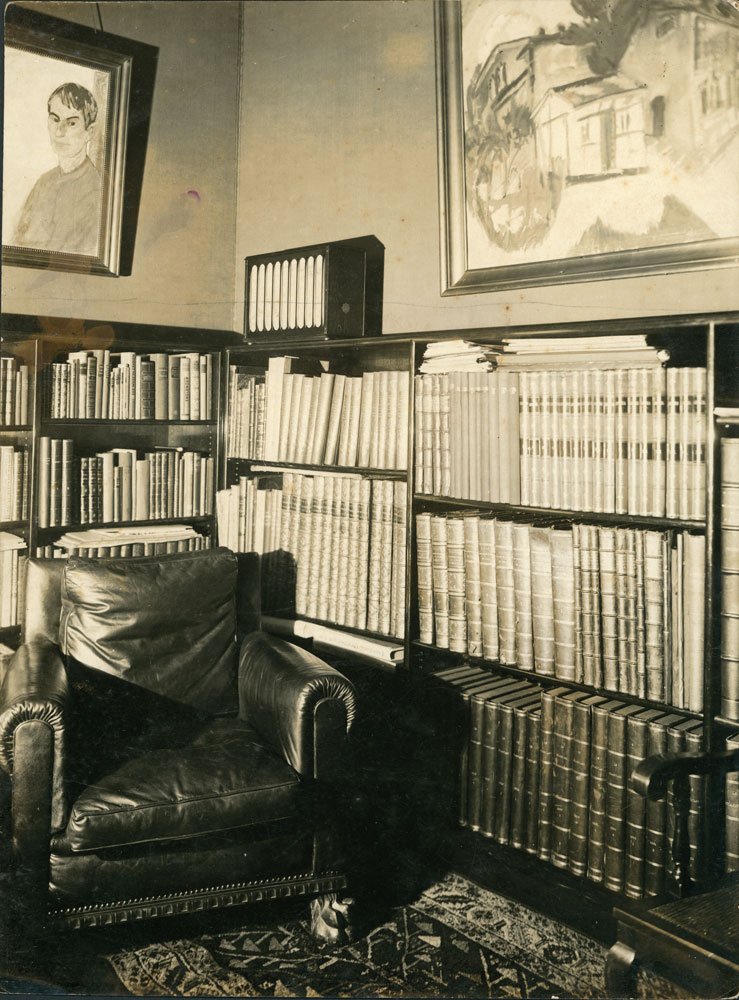

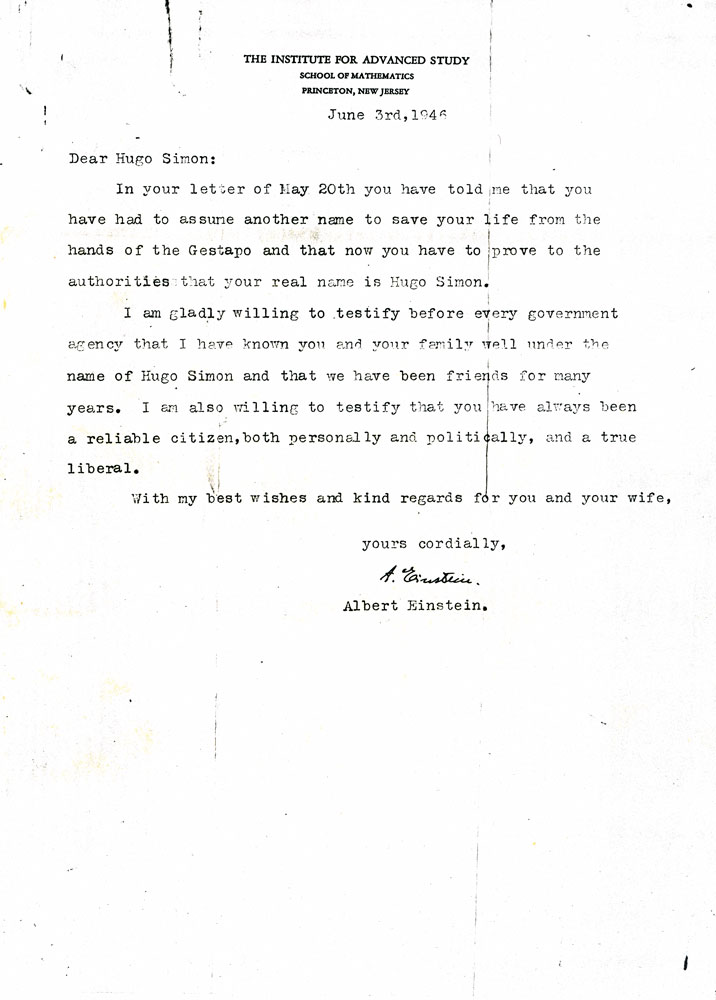

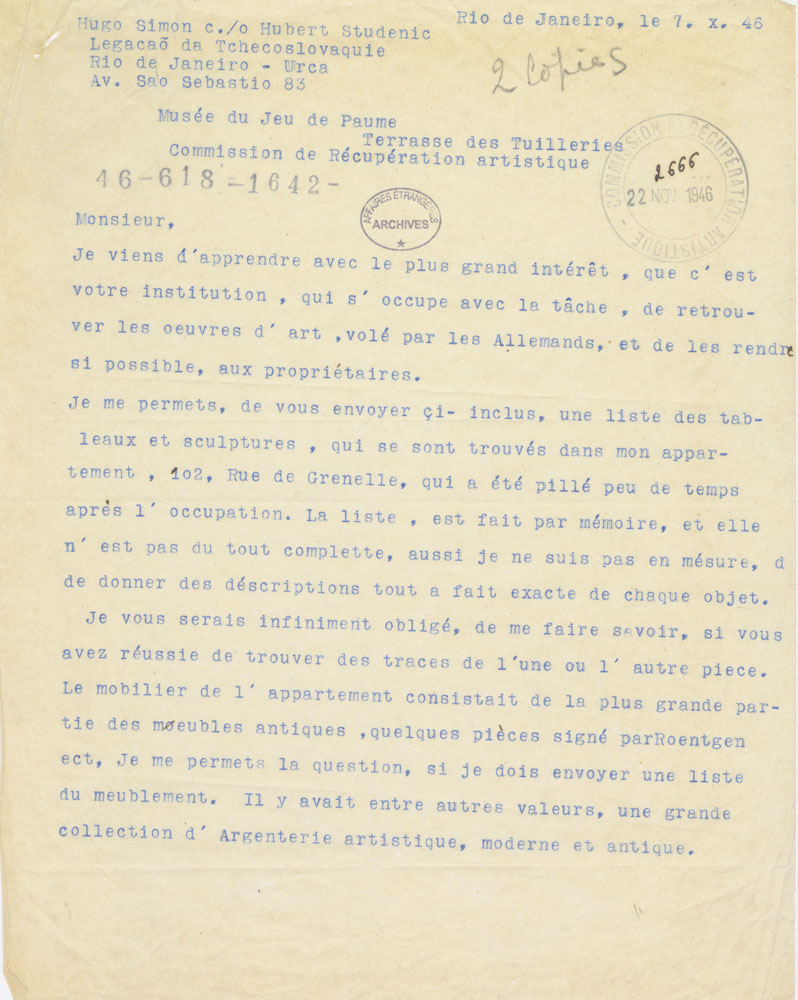

The lender was quickly identified: a man named Hugo Simon. A German Jewish banker, collector, and patron, Simon was a prominent figure in the artistic circles of the Weimar Republic. A committed supporter of the Expressionist movement, he served on various museum acquisition committees, maintained close ties with dealer Paul Cassirer, and hosted a vibrant intellectual salon with his wife Gertrud. Amongst their guests were Bertolt Brecht, Stefan Zweig, Thomas Mann, and Albert Einstein.

The couple’s extensive collection included works by many of the leading names in modern German art: Ernst Barlach, Lyonel Feininger, George Grosz, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Franz Marc, Georg Kolbe, Ludwig Meidner, Otto Müller — and Max Pechstein.

In March 1933, Hugo and Gertrud Simon were forced to flee Germany. They settled in Paris, where their daughter Ursula was already living with her husband, the German sculptor Wolf Demeter — a student of Aristide Maillol — and their son, Marc. In October of that same year, the Simon family’s property was confiscated by the Nazi regime.

Nevertheless, they managed to smuggle part of their valuable collection out of Germany.

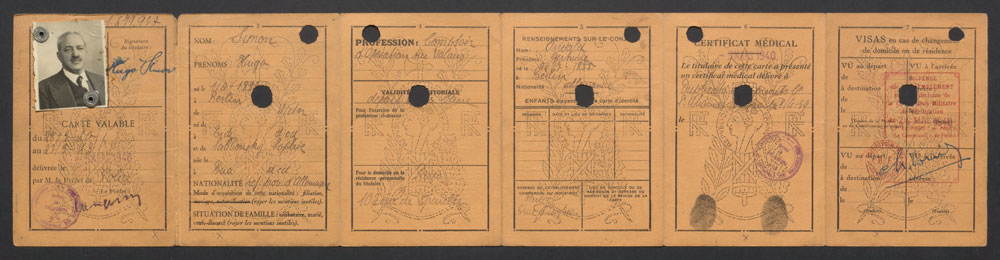

In Paris, Hugo Simon resumed his work as a banker while becoming actively involved in supporting German refugees and anti-Nazi artists. His activism made him a target of the Gestapo: in October 1937, he was stripped of his German citizenship and denounced by the Nazis as a “typical Jewish Marxist capitalist.”

In October 1937, Hugo Simon was stripped of his German citizenship and denounced by the Nazis as a “typical Jewish Marxist capitalist.”

Like many German refugees, Simon was also monitored by the French police, who suspected him — amongst other unfounded allegations — of arms trafficking. Under growing financial pressure, and much like the character seen at the beginning of the 1976 film Monsieur Klein, starring Alain Delon, Hugo Simon was forced to part with some of his masterpieces at rock-bottom prices.

Reluctantly, he sold The Scream by Edvard Munch in 1938 — a painting he had owned since 1926.

In June 1940, as German troops marched into Paris and the noose tightened, Hugo and Gertrud Simon fled to Marseille, hoping to secure visas for the United States. They soon found themselves trapped — the Vichy regime had agreed to hand over German dissidents.

The couple managed to obtain false identity papers from the Czechoslovak consul, under the names “Hubert and Garina Studenic”. Their daughter Ursula, her husband Wolf Demeter, and their other daughter Annette received passports under the names “Léonie Renée Denis”, “André Denis” and “Marie-Louise Pecherman”. Ursula’s son, Marc Roger Demeter, born in 1931, became “Roger Denis”. Together, they crossed the Pyrenees into Spain, and from there, embarked on a boat for Brazil.

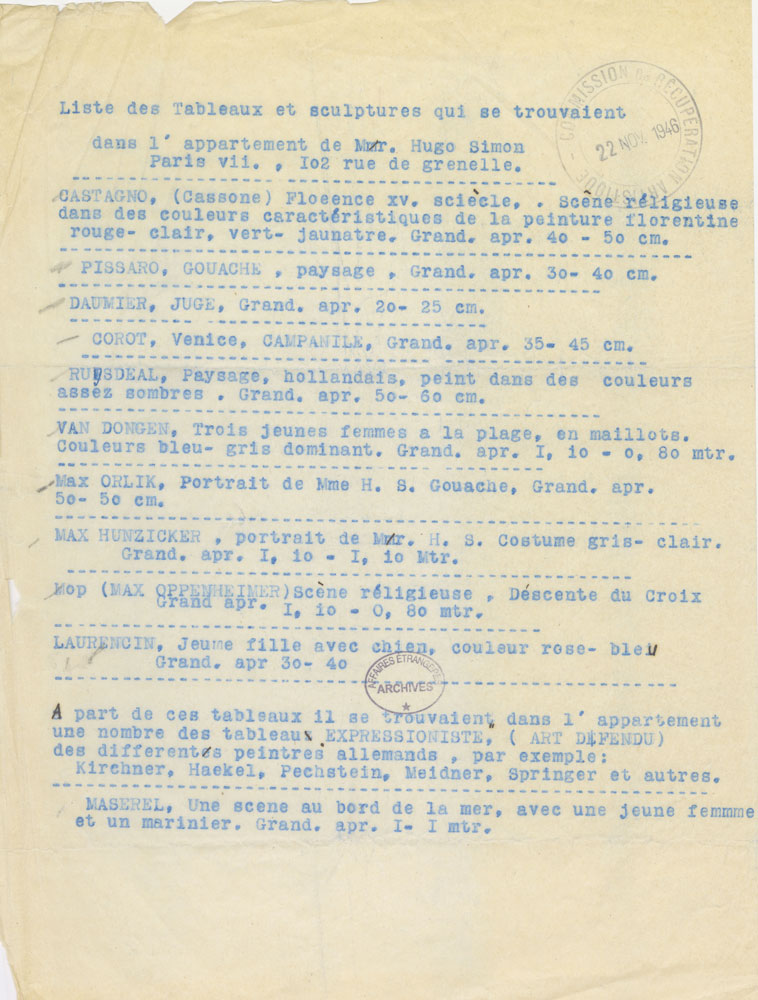

In 1941, the apartment of Hugo and Gertrud Simon, at 102 rue de Grenelle in Paris’s 7th arrondissement, was largely emptied by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the Nazi task force dedicated to plundering cultural property. Some of the Simon collection was transferred to the Jeu de Paume, while other works were left behind. Simon’s office on rue d’Antin in the 2nd arrondissement was also ransacked.

In 1941, the apartment of Hugo and Gertrud Simon, at 102 rue de Grenelle in Paris’s 7th arrondissement, was largely emptied by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the Nazi task force dedicated to plundering cultural property.

By March 1941, Hugo and Gertrud had reached Brazil, living under assumed identities. They first went into hiding in Rio. Branded as “undesirable immigrants” by the Brazilian government and threatened with expulsion, they fled to the Minas Gerais region, where they purchased a small property and began raising silkworms. Agriculture had long been one of Hugo Simon’s passions, but the venture proved far from profitable for the couple.

For Simon, the silkworm — a creature that no longer exists in the wild and can only survive through artificial breeding — became a metaphor for the German Jew he had been, dependent on a society that no longer wanted him. In this world of exile, hardship, and hidden identities, Simon reconnected with Georges Bernanos, who had settled in Barbacena, and met Stefan Zweig shortly before Zweig’s suicide.

During this period, Hugo Simon wrote an autobiographical novel, Seidenraupen (Silkworms), which remained unpublished. He died in São Paulo in 1950. Gertrud Simon passed away in 1964. The rest of the family remained in Brazil.

After the war, Hugo and Gertrud Simon resumed their true identities, though not without difficulty. Their daughter and son-in-law, however, kept their wartime alias of “Denis.”

Unable to travel for lack of papers and resources, Hugo Simon began — from afar — the arduous process of trying to recover his possessions, either looted by the Nazis or left behind in his former home in Paris . In 1946, he declared before the Commission de Récupération Artistique that he had owned “a number of Expressionist paintings (forbidden art) by various German artists, including Kirchner, Heckel, Pechstein, Meidner, Springer”. In the end, he was able to secure only a handful of restitutions.

In 2017, Rafael Cardoso Denis, great-grandson of Hugo Simon, initiated official proceedings with the Commission for the Compensation of Victims of Anti-Semitic Spoliation (CIVS), seeking recognition of the French state’s wrongful acquisition of the painting.

Born in Brazil in 1964, he only discovered the troubled history of his great-grandparents in adulthood. An art historian himself, specializing in 19th- and 20th-century Brazilian art, he has devoted himself to preserving the memory of Hugo Simon and reconstructing his story. In 2016, he published Das Vermächtnis der Seidenraupen (The Legacy of the Silkworm), a fictionalised biography of his great-grandfather.

Together with his mother — widow of Marc Roger Demeter/Roger Denis, Hugo Simon’s grandson — and his brother André Lúcio, they are the three legal heirs of Hugo Simon.

On July 1, 2021, Rafael Cardoso Denis attended the restitution ceremony with both pride and emotion: “For Hugo Simon, this would be a moment of immense joy — to find himself here once again, alongside his Pechstein painting. We have entered a time of reconciliation; it is a powerful political signal. Twenty years ago, this would not have been possible.”

For Hugo Simon, this would be a moment of immense joy — to find himself here once again, alongside his Pechstein painting. We have entered a time of reconciliation; it is a powerful political signal.

Rafael Cardoso Denis, great-grandson of Hugo Simon

With the help of Didier Schulmann, Rafael Cardoso patiently pieced the puzzle together. In the 2010s, Schulmann’s investigation led him to the archives of the Banque de France and even to Aix-en-Provence, at the Archives Nationales de la France d’Outre-Mer. After Hugo Simon’s departure from France in 1940, the Banque de l’Algérie, which had become the owner of the apartment on rue de Grenelle, took possession of the contents, treating them as collateral for Simon’s unpaid rent.

Thousands of pages examined in Aix and Paris — notes, reports, and correspondence from various departments of the Banque de l’Algérie — reveal that as early as late summer 1944, with the aim of re-letting Simon’s former apartment, the bank had a bailiff break the seals imposed by the Nazis. The flat, though ransacked, was not empty. Two successive inventories were drawn up, listing several dozen pieces of period furniture, decorative objects, and four paintings deemed “without value”.

After Simon’s departure in 1940, the Banque de l’Algérie, which had become the owner of the apartment on rue de Grenelle, took possession of the contents, treating them as collateral for Simon’s unpaid rent.

Where was the Pechstein at this moment in time? And how did it make its way from rue de Grenelle to the Palais de Tokyo? Did it remain in the apartment until the end of the war, disappearing in the shuffle of people coming and going, as the owner sought to recover unpaid rent? Was it included in the auction — for which the records were destroyed — that took place on March 2 and 3, 1964, dispersing the movable property of the Banque de l’Algérie, including furniture flagged in liquidation inventories as belonging to Hugo Simon? We still do not know.

A new lead then emerged. Research suggested that the painting may have been loaned to the “Exposition d’art allemand libre”, held in November 1938 at the Maison de la Culture on rue d’Anjou in Paris. Organized by Paul Westheim and Eugen Spiro, the exhibition featured several works lent by Hugo Simon, including a painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. This confirms that the Pechstein was in the possession of Hugo and Gertrud Simon on the eve of the war, and amongst the works they were forced to abandon when they fled.

According to Rafael Cardoso Denis, “the most likely scenario is that someone kept the painting for twenty-five years, somewhere, between the moment it disappeared and its reappearance in 1966 in the storage of the Musée National d’Art Moderne”.

One thing is certain: it was because of the German occupation of Paris, and the grave threats hanging over him due to his religion and political commitments, that Hugo Simon had to flee the city with his family — leaving behind, and ultimately losing, his possessions, including the Max Pechstein painting.

Given that proper procedures for accession into the national collections had not been followed, the painting’s entry into the French state inventory in 1966 was deemed unfounded. It was struck from the records as an “improper entry” and transferred to the provisional special inventory of works recovered after the war, commonly referred to as the “MNR”, under number R 29 P.

On July 1, 2021, Vier Akte in Landschaft and Hugo Simon were at last reunited at the Centre Pompidou. ◼

Max Pechstein’s Nus dans un paysage was also lent by the heirs for the exhibition Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art at the Jewish Museum, New York (August 20, 2021 – January 9, 2022).

Related articles

Max Pechstein, Nus dans un paysage, or Paysage [Vier Akte in Landschaft], 1912

Oil on canvas, 71 × 80 cm (detail)

© Pechstein Hamburg / Toekendorf / Adagp, Paris

© Centre Pompidou / Photo: Ph. Migeat / Dist. Rmn-GP

![Max Pechstein, « Paysage » [Vier Akte in Landschaft], 1912 - repro](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/5/csm_20210701-pechstein-paysage-mag_8ccfa01ab4.jpg)

![Max Pechstein, « Paysage » [Vier Akte in Landschaft], 1912 - dos de la toile](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/a/csm_20210701-pechstein-toile-dos-mag_3b644e0cc8.jpg)