Tracking the Ghost Paintings of Fédor Löwenstein, Lost to Nazi Looting

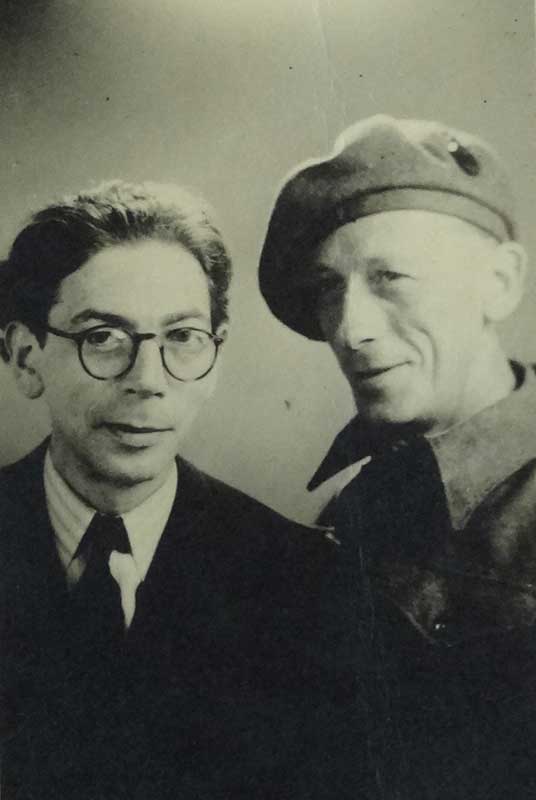

In the spring of 1940, as German forces advanced on Paris, Fédor Löwenstein was preparing to flee the city. Before his departure, however, the painter made a final attempt to ship twenty-five of his canvases by boat from the port of Bordeaux. His works, which hovered between Cubism and abstraction, were destined for an exhibition at the Nierendorf Gallery in New York.

Born in Munich in 1901 to a Jewish family, Löwenstein held Czechoslovak nationality. On May 11, 1940, he wrote to his partner, the artist Marcelle Rivier (1906–1986): “It won’t be until Monday that I’ll know whether my paintings will be sent off — or if I must abandon that dream. I have a bad feeling about it.”

Tragically, Löwenstein’s premonition proved right. His crates never left Warehouse H. Worse still, they were seized on December 5, 1940, and transferred in early 1941 to the Jeu de Paume depot in Paris.

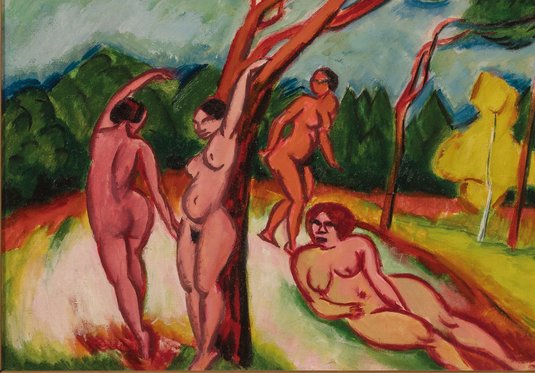

Tragically, Löwenstein’s premonition proved right. His crates never left Warehouse H. Worse still, they were seized on December 5, 1940, and transferred in early 1941 to the Jeu de Paume depot in Paris. There, they were placed in what came to be known as the museum’s “salle des martyrs” — a space where artworks deemed “degenerate” by the Nazi regime were left to languish. Several of the artist’s paintings were marked with a large red chalk cross by agents of the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg), the task force responsible for looting Jewish property — a sign that condemned them to destruction. And yet, by some miracle, three of Löwenstein’s paintings from 1939 survived.

For decades, their provenance unknown and their significance overlooked, the works sat in storage on the ground floor of the Louvre. In 1973, they were mistakenly entered into the official inventory of the Musée National d’Art Moderne as an “anonymous donation”. Shortly before the museum’s relocation, the paintings were moved to the reserves of the Centre Pompidou.

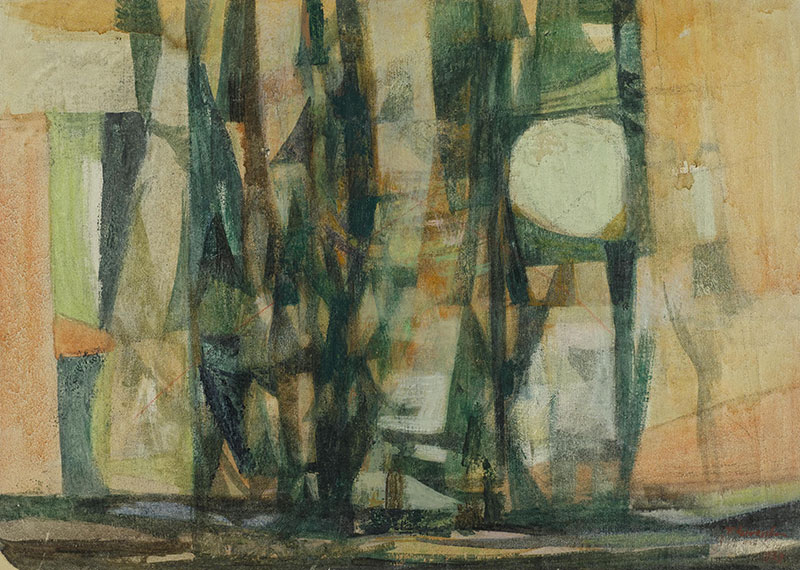

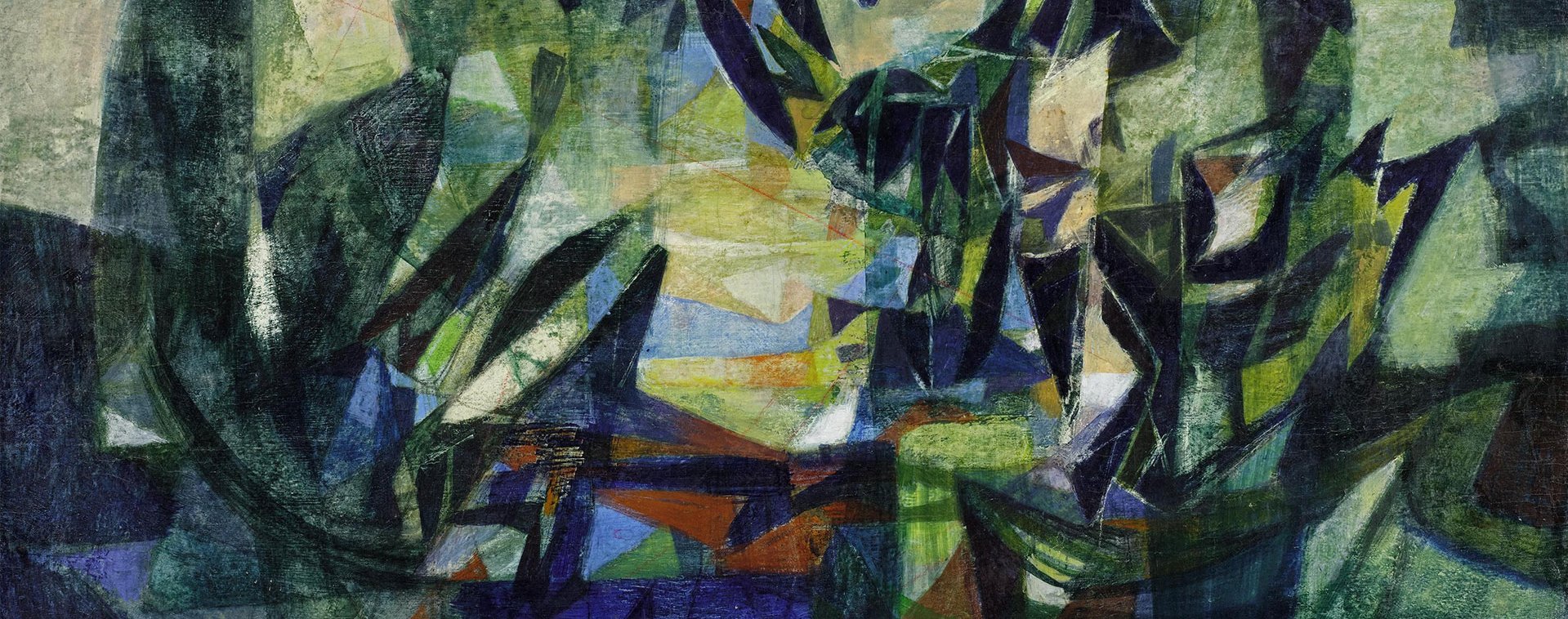

In December 2010, following a lengthy investigation, Arbres, Composition, and Les Peupliers were formally identified as looted works. They were subsequently removed from the museum’s official inventory and reclassified as part of the Musées Nationaux Récupération — or “MNR” — collection (see box below).

On September 16, 2025, at the Centre Pompidou, the paintings were finally returned to the artist’s great-nephew.

“These works bear the dramatic marks of history,” explains Camille Morando, referring to the red crosses still visible on the canvases — particularly on Arbres — like stigmata. Morando, who oversees the documentation of the modern collections at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, adds that two of the paintings also show “signs of laceration along the edges, where they were torn from their stretchers”.

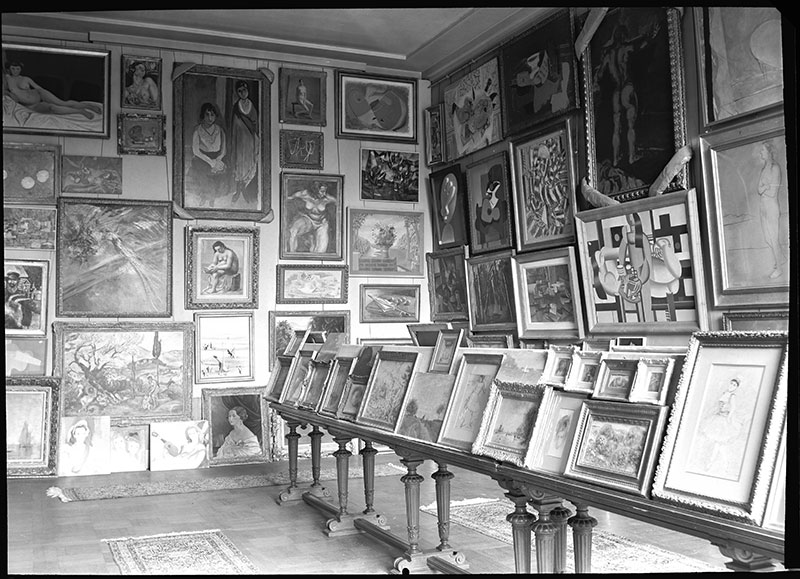

Camille Morando has been following the Löwenstein case since the early 2010s. She was the one who welcomed researchers Alain Prévet (National Museums Archives) and Thierry Bajou (chief curator), the first to identify a painting by Löwenstein while studying the only two known photographs taken in 1940 by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg of Room 15 — the salle des martyrs — at the Jeu de Paume.

These works bear the dramatic marks of history.

Camille Morando, Musée national d'art moderne

The two photographs depict Room 15 on a day in late 1940 (the museum had been placed at the disposal of the ERR as of November 1, 1940, ed.). Regularly, the space was rehung to showcase the artworks for high-ranking Nazi officials who would stop by to “shop” — chief amongst them was Hermann Goering, who visited the premises some twenty times between November 1940 and November 1942.

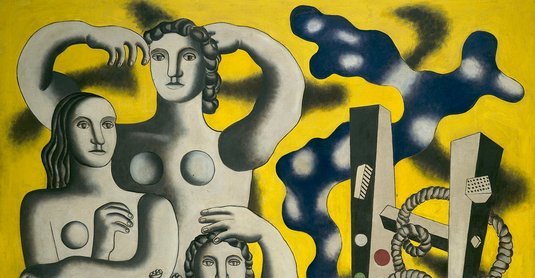

In one of the black-and-white images, taken with a large-format camera in natural light, Composition by Fédor Löwenstein can be seen tucked in a corner — alongside works by Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, and Henri Matisse.

In À la trace, a podcast by the Ministère de la Culture dedicated to the journey of artworks looted by the Nazi regime, Alain Prévet recounts the astonishing discovery:

“No one had recognised the Löwensteins before. It was through studying the negatives of those two images, preserved in the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that we were able to identify them. Once they were digitised in ultra-high resolution, we could isolate and examine each work individually — the level of detail was far superior to what paper prints offered. You could even make out a signature and a date: 1939.”

The paintings were identified by cross-referencing this new material with the archives of Rose Valland. An assistant curator at the museum during the Occupation, Valland is now considered a heroic figure of the Resistance. It is thanks to her that we have records of hundreds of looted works that passed through the Jeu de Paume. After the Nazis withdrew in 1944, she joined the effort to locate and recover works sent to Germany — a mission that became known as récupération artistique.

At great personal risk, Valland observed the constant movement of confiscated artworks, noting everything — artists’ names, dimensions, destinations — and passing the information along piece by piece.

The paintings were identified by cross-referencing this new material with the archives of Rose Valland. An assistant curator at the museum during the Occupation, Valland is now considered a heroic figure of the Resistance.

Löwenstein’s name appears on Rose Valland’s list: the artist’s three paintings are catalogued under ERR record numbers Löwenstein 4 (Paysage), 15 (Les Peupliers), and 19 (Arbres). The records even bear the annotation vernichtet — “destroyed”.

And yet, Löwenstein’s three paintings did not end up in flames in the Tuileries Garden, as was the fate of hundreds of others. Their trail went cold. The works remained in storage at the Louvre, before resurfacing in 1973 and being — erroneously — entered into the museum’s general inventory during an administrative effort to regularize unclaimed artworks found in the collection.

In June 1940, Löwenstein left the capital at the last minute for Mirmande — the German army entered Paris on June 14. Here, in the Drôme region, he rejoined a circle of Jewish artists and resistance members, along with Marcelle Rivier. He spent part of the war there, while also traveling at times to Nice, and even back to Paris in 1943 to see a doctor.

After the war, Löwenstein never claimed his paintings. Did he believe they had been destroyed or lost? Suffering from lymphoma — a then-incurable cancer — since 1943, the artist died in Nice in 1946.

After the war, Löwenstein never claimed his paintings. Did he believe they had been destroyed or lost?

In 2014, for the first time, Löwenstein’s works were shown at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux — the very place where everything had come to a halt for him.

In 2021, Composition finally made its transatlantic journey. It was featured in the exhibition Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art at the Jewish Museum in New York. ◼

MNR Works: Piecing Together a Fragmented History

At the end of the Second World War, many artworks recovered in Germany were returned to France, having been looted from French territory. While three-quarters of them were restituted to their rightful owners, 13,000 were sold by the French state, and approximately 2,200 were placed under the care of national museums — and often deposited in regional institutions. Legally, the French state is only a temporary custodian of these works. As such, they are not considered part of the permanent public collections of France’s national museums. The acronym MNR — Musées Nationaux Récupération — refers to this group of approximately 2,200 artworks. On museum wall labels, the MNR designation signals this complex history. (At the Musée National d’Art Moderne, these works are not labeled MNR, but “RxP”; the three Löwenstein paintings, for instance, are inventoried as R26P, R27P, and R28P.)

To this day, many MNR works remain in limbo, their provenance still unclear. When a case of looting can be definitively established, the path is opened for restitution.

Related articles

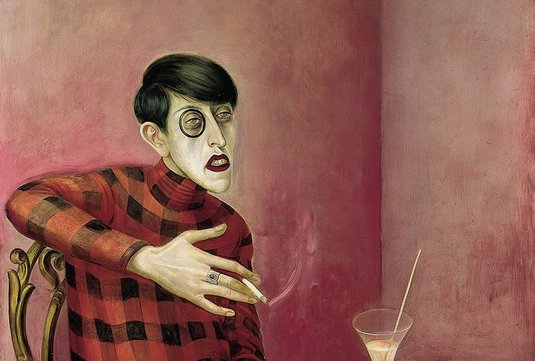

Fédor Löwenstein, Composition (1939)

Erroneously entered into the museum’s general inventory in 1973; removed and reclassified in 2011 in the provisional special inventory of works recovered after the war.

MNR: Artwork recovered at the end of the Second World War

Restituted in September 2025 to the artist’s rightful heirs.

Photo © Centre Pompidou / Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

Photograph by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR)

© Archives des musées nationaux, Paris