Lionel Sabatté, The Alchemy of Dust

“I was just picking up some dust from the freezer in my studio in Noisy,” says Sabatté, casually, by way of an apology for being late. It sounds like a line from a deadpan short story. And yet, in the world of contemporary art—where urgency, ecology, and corporeality increasingly intersect—it makes a certain kind of sense. A finalist for this year’s Duchamp Prize, Sabatté has carved out an unusual position among his generation of French artists. Rather than working with the ‘noble’ materials of traditional sculpture, he collects remnants of the living: human dust, dead skin, hair, fabric fibers, fragments of wood and volcanic stone. Materials on the verge of vanishing.

Rather than working with the ‘noble’ materials of traditional sculpture, he collects remnants of the living: human dust, dead skin, hair, fabric fibres, fragments of wood and volcanic stone.

Seated on a bench inside the Musée d’Art Moderne, where this year’s 25th edition of the prize is on view, the artist—in his late forties —speaks in a soft, even voice about the path that brought him here. Drawing, he says, was something that took hold early. “It was hard to stop. I drew everywhere—on all my books. It was like breathing.” More than a skill, it was a reflex. “I knew right away it would always be part of my life.”

And yet, the path to becoming an artist was anything but direct. Raised in Toulouse, with time spent in Montauban and in Réunion, Sabatté initially imagined a career in physical education. He studied sports science in Orsay, on the outskirts of Paris. It was only at 21, after a friend brought him to the art school in Nancy, that something shifted. “I discovered another way of thinking about the body, about time and matter,” he recalls. He enrolled soon after at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris, where a deep knowledge of anatomy informed his practice in painting and sculpture.

My practice isn’t really of the art world.

Lionel Sabatté

Those years also taught him restraint. “Studying gave me the distance to look at what I was doing,” he says. “My work as an artist is mostly about cutting back something that’s always overflowing. Without that, I’d just be a guy on the margins making things.” After graduating in 2003, Sabatté took an independent route—outside the systems and cycles of the institutional art world. “My practice isn’t really of the art world,” he says plainly.

In collaboration with Art Basel Paris

His radicalism, if we can call it that, lies in something quieter. He recalls an early encounter with the Nouveaux Réalistes at the Centre Pompidou—artists who also found value in discarded materials. But Sabatté’s approach is less urban, more organic. His signature medium: dust. This overlooked, ubiquitous residue of human life—composed of hair, eyelashes, fabric particles, mineral traces. “I love dust,” he says, “because it’s free, and it belongs to all of us.” (He keeps it in a freezer, to prevent moths.)

I love dust because it’s free, and it belongs to all of us.

Lionel Sabatté

For the Duchamp Prize, Sabatté swept the floors of the museum itself—its corners, its forgotten spaces—gathering what remained after cleaning crews had passed through. From this, he created a new series of dust drawings: pale mosaics on white paper, forming spectral faces that seem to emerge from the walls. “You see the traces of everyone who’s been here,” he says. Each fragment holds a memory—skin cells, hair—evidence of decay, but also of continuity. For Sabatté, what we discard is not waste, but a testimony.

For the Duchamp Prize, Sabatté swept the floors of the museum itself—its corners, its forgotten spaces—gathering what remained after cleaning crews had passed through.

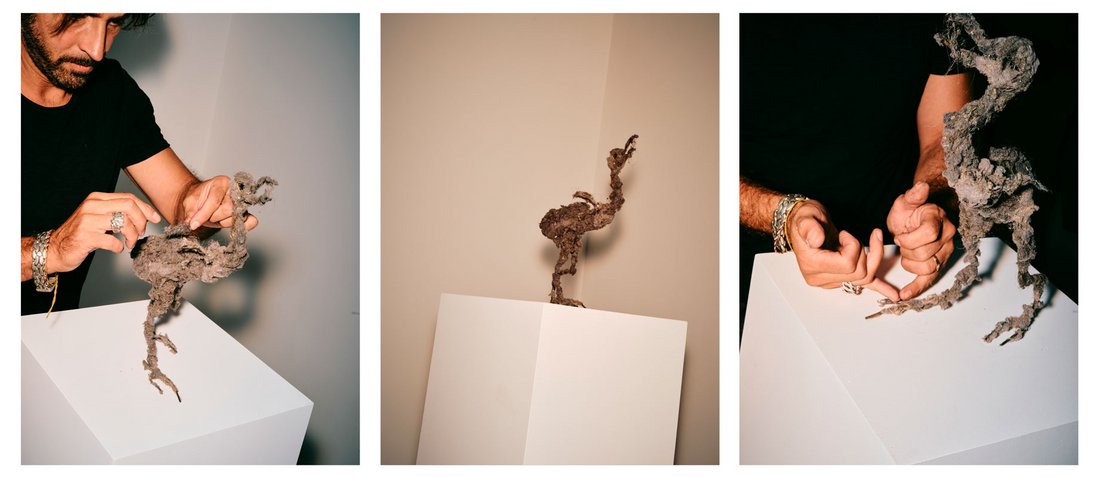

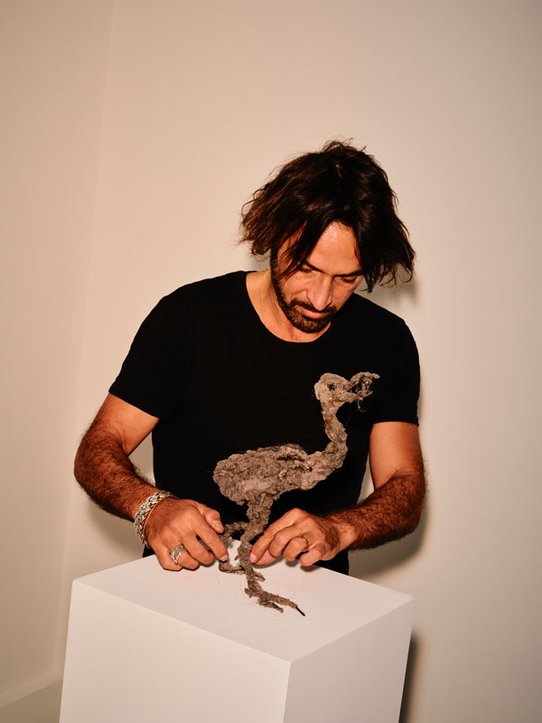

This vision is embodied, literally, in a small sculpture placed near the entrance: a juvenile dodo made entirely of dust. The extinct bird—ungainly, flightless, and often used as shorthand for human folly—becomes, in his hands, a vessel of quiet mourning. This one, created in the aftermath of COVID, is composed entirely of dust collected from the corridors of the Châtelet–Les Halles metro station, the sculpture thus containing the genetic imprint of the very species that brought it to extinction. A kind of poetic justice—part memorial, part rebirth.

In a later room, a series of birds made from pouzzolane—a porous volcanic stone—and lime (the same material used in ancient Roman mortar) seem to emerge from geological time. Towering, ambiguous figures—part dinosaur fossil, part elderly bird—these hybrid creatures stand like sentinels on a shifting landscape. They speak less to apocalypse than to metamorphosis.

What makes Sabatté’s proposal for the Duchamp Prize so compelling is his sense of space—not just how to fill it, but how to invite viewers to move through it. “The space allowed for something to unfold,” he says. “Almost like a choreography.” This immersive, almost choreographic sensibility recalls the artist Bruce Nauman, whose work Sabatté first encountered at the Centre Pompidou in the late ’90s—and who left a lasting impression.

Elsewhere in the exhibition: a suspended square of fabric made from dead skin, and a large canvas created specifically for the show—painted directly on the floor of his studio. “They’re like imagined geologies,” he explains, “from which new forms of life might emerge. I imagine other planets, volcanic activity, tectonic movement. It’s as if all the other pieces could have been born from this one.”

My works are like imagined geologies from which new forms of life might emerge. I imagine other planets, volcanic activity, tectonic movement.

Lionel Sabatté

And perhaps they were. At its core, Sabatté’s practice is not about permanence but about transformation—about what survives and what shifts shape. His works invite us to look again at what we overlook. To see dust not as the end of things, but as the beginning of something else. ◼

Lionel Sabatté is represented by Galerie Ceysson & Bénétière, Paris

Related articles

In the calendar

Artist Lionel Sabatté during the exhibition installation

Photo © Guillaume Blot